How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 2/7 Company Section

One of many things you’ll probably need to finance an independent film is a business plan. Here’s an outline of one of the sections you’ll need to write.

Last time we went over the basics of writing an independent film executive summary. This time, we’re diving into the first section of a business plan. By this I mean the company section. If you want an angel investor to give you money, they’re going to need to understand your company. There are some legal reasons for this, but most of it is about understanding the people that they’re considering investing in.

The company section generally consists of the following sub-sections. This section only covers the company making the film, not the media projects themselves. Those will be explored in section III - The Projects.

FORM OF BUSINESS OWNERSHIP

This is the legal structure you’ve chosen to form your company as. If you have yet to form a company, you can tell an investor what the LLC will be formed as once their money comes in. I’ve written a much longer examination of this previously, which I’ve linked to below. Also, I’m Not a Lawyer, that’s not legal advice, don’t @ me.

Related: The Legal Structure of your Production Company

THE COMPANY

This subsection talks a bit about your production company. You can talk about how long you’ve been in business, what you’ve done in the past, and how you came together if it makes sense to do so. Avoid mentioning academia if at all possible, unless you went to somewhere like USC, UCLA, NYU, or an Ivy League School. Try to make sure this section only takes up 2-3 lines on the page.

BUSINESS PHILOSOPHY

This is what you stand for as a company. What’s your vision? What content do you want to make over the long term? Why should an investor back you instead of one of the other projects that someone else solicited?

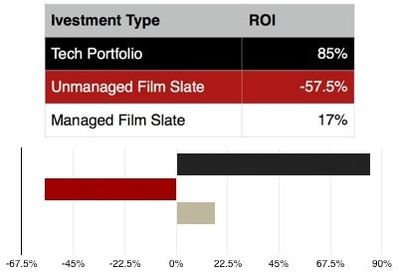

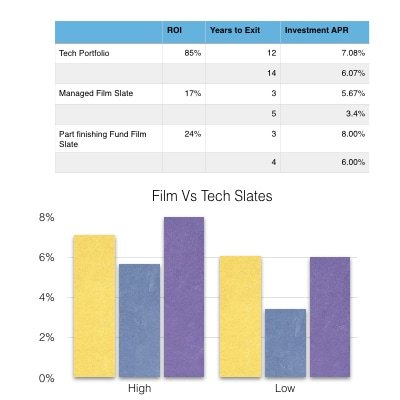

Your film probably can’t compete with the potential return of a tech company. I’ve explored that in detail over the 7 part blog series linked below.

Additionally, you might want to check out Primal Branding by Patrick Hanlon it’s a great book to help you better understand how to write a compelling company ethos. I use it with clients as it frames it exceptionally well for creative people. That is an affiliate link.

Related: Why don’t rich Tech people invest in film?

Since you can’t compete on the merits of your potential revenue alone, you need to show them other reasons that it would behoove them to invest in your project. See the link below for more information.

Related: Diversification and Soft Incentives

PRODUCTION TEAM

These are the key team members that will make your film happen. List the lead producer first, the director second, the Executive Producer second, and the remaining producers after that. Directors of photography and composers tend to not add a lot of value in this section, but if you’ve got one with some impressive credits behind them, it might make sense to add the.

Generally, if you have someone on your team with some really impressive credits, it might make more sense to list them ahead of the order I listed above.

Essential Reference Books for Indiefilm Business Planning

PRODUCT

This should talk a little about the films you’re going to make, and the films you’ve made in the past.

OPERATIONS

This is a calendar of operations with key milestones that you intend to hit during the production of the film. These would be things like:

Financing Completed

Preproduction Begins

First Day of Principle Photography

Completion of principal Photography

Start of post-production

You’ll also want to include when you intend to finish post-production, as well as when you intend to start distribution, but that should be less specific than the items listed above. For the non-bullied items, I would say that you should just give a quarter of when you expect to have them happen, whereas the bullets should be a month or a date.

CURRENT EVENTS

The Current events are as they sound, a list of the exciting events going on with your film and with your company. This could be securing a letter of intent from an actor, director, or distributor, completing the script, or raising some portion of the financing.

Assisting filmmakers in writing business plans is a decent part of the consulting arm of my business. The free e-book, blog digests, and templates in my resource package can give you a big leg up. That said, If this all feels like a bit much to do on your own you might want to check out my services page. Links for both are in the buttons below.

Thanks so much for reading! You can find the other completed sections of this 7 part series below

Executive Summary

The Company (This One)

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-forma Financial Statements.

Check the tags for more related content.

How to Write an Independent Film Business Plan - 1/7 Executive Summary

If you want to raise money from an investor, you have to do your homework. That includes making a business plan. A business plan starts with an executive summary.

One of my more popular services for filmmakers is Independent Film Business Plan Writing. So I decided to do a series outlining the basics of writing an independent film business plan to talk about what I do and give you an idea of how you can get started with it yourself.

Before we really dive in it’s worth noting that what will really sell an investor on your project is you. You need to develop a relationship with them and build enough trust that they’ll be willing to take a risk with you. A business plan shows you’ve done your homework, but in the end, the close will be around you as a filmmaker, producer, and entrepreneur.

The first Section of the independent film business plan is always the Executive Summary, and it’s the most important that you get right. So how do you get it right? Read this blog for the basics.

Write this section LAST

This section may be the first section in your independent film business plan, but it’s the last section you should write. Once you’ve written the other sections of this plan, the executive summary will be a breeze. The only thing that might be a challenge is keeping the word count sparse enough that you keep it to a single page.

If you have an investor that only wants an executive summary, then you can write it first. But you’ll also need to generate your pro forma financial statements for your film, and project revenue and generally have a good idea of what’s going to go into the film’s business plan in order to write it. I would definitely write it after making the first version of your Deck, and rewrite it after you finish the rest of the business plan.

Keep it Concise

As the name would imply, the Executive Summary is the Summary of an entire business plan. It takes the other 5 sections of the film’s business plan and summarizes them into a single page. It’s possible that you could do a single double-sided page, but generally, for a film you shouldn’t need to.

A general rule here is to leave your reader wanting more, as if they don’t have questions they’re less likely to reach out again, which gives you less of a chance to build a relationship with them.

Here’s a brief summary of what you’ll cover in your executive summary.

Project

As the title implies, this section goes over the basics of your project. it goes over the major attachments, a synopsis, the budget, as well as the genre of the film. You’ll have about a paragraph or two to get that all across, so you’ll have to be quite concise.

Company/Team

This section is a brief description of the values of your production company. Generally, you’ll keep it to your mission statement, and maybe a bit about your key members in the summary.

Marketing/Distribution

In a standard prospectus, this would be the go-to-market strategy. For a film, this means your marketing and distribution sections. For the executive summary, list your target demographics, whether you have a distributor, plan to get one, or plan on self-distributing. Also, include if you plan on raising additional money to assist in distribution.

SWOT Analysis/Risk Management

SWOT is an acronym standing for Strengths Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. For the executive summary, this section should include a statement that outlines how investing in film is incredibly risky, due to a myriad of factors that practically render your projections null and void. Advise potential investors to should always consult a lawyer before investing in your film. Cover your ass. I’ve done a 2*2 table with these for plans in the past, and it works reasonably well. Speaking of covering one’s posterior, you should have a lawyer draft a risk statement for you. Also, I am not one of those, just your friendly neighborhood entrepreneur. #NotALawyer #SideRant

Financials

Finally, we come to the part of the plan that the investors really want to see. How much is this going to cost, and what’s a reasonable estimate on what it can return? There are two ways of projecting this, outlined in the blog below.

Related: The Two Ways to Project Revenue for an independent film.

In addition to your expected ROI, you’ll want to include when you expect to break even and mention that pro forma financial statements are at the end of this plan included behind the actual financial section.

Pro Forma Financial Statements.

If you’re sending out your executive summary as a document unto itself, you will strongly want to consider including the pro forma financial statements. For Reference, those documents are a top sheet budget, a revenue top sheet, a waterfall to the company/expected income breakdown, an internal company waterfall/capitalization table, a cashflow statement/breakeven analysis, and a document citing your research and sources used in the rest of the plan.

Writing an executive summary well requires a lot of highly specialized knowledge of the film business. It’s not easy to attain that knowledge, but my free film business resource package is a great place to start! You’ll get a deck template, contact tracking templates, a FREE ebook, and monthly digests of blogs categorized by topic to help you know what you’ll need to have the best possible chance to close investors.

Here’s a link to the other sections of this 7 part series.

Executive Summary (this article)

The Company

The Projects

Marketing

Risk Statement/SWOT Analysis

Financials Section (Text)

Pro-Foma Financial Statements.

5 Rules for Finding Film Investors

If you want to make a movie, you need money. If you don’t have money, you probably need investors. Here’s how you find them.

One of the most common questions I get is where to find investors for a feature film. Inherent in that question is simply where to find investors. While I may not have a specific answer for you regarding exactly where to find them, I do have a set of rules for figuring out where you might be able to find them in your local community. This is meant to be applicable outside of the major hubs in the US, and as such it’s not going to have to be more of a framework than a simple answer.

Would you rather watch or listen than Read? Here's the same topic on my YouTube Channel.

Like and Subscribe!

1. Go where the money is.

Think about where people in your community who have money congregate. In San Francisco, the money comes from tech. In Colorado, the money came from oil, gas, and tourism, but has recently grown to include legal recreational marijuana. In many communities, some of the most affluent are the doctors and medical professionals. In most communities, the local lawyers tend to have money, but you’ll have to make sure you come prepared. Figure out what industries drive your local economy and then extrapolate from that who might have enough spare income to invest in your project.

If you know what these people do, then you can start to figure out where they go when it’s after working hours. If you know where they go after hours, you can go get a drink and start to work your way to making a new friend in this investor.

All that being said, Be careful not to solicit too early, as that can actually be illegal. #NotALawyer.

2. Figure out a place where you can find something in common

Any investment as inherently risky and a-typical as the film industry relies heavily on your relationship with your investor. As such, finding something you have in common is a great way to start the relationship right.

RELATED: 7 Reasons Courting an Investor is Like Dating

As an example of what I mean, I’ve met investors while singing karaoke at Gay bars in San Francisco. I’ve met others at industry events, and I’ve even met a few by going to some famous silicon valley hot spots where investors and Venture Capitalists are known to congregate. If you know where all the doctors go to drink after work, and if there’s a regular activity at one of the bars that can facilitate meeting them, it might not be a bad idea to go and try to establish some connections in that community. This segues us nicely to…

3. Understand that moneyed people tend to have their own community

Generally, wealthy individuals know other wealthy individuals. If you develop a relationship with someone within that community, it means that even if that investor you ended up establishing a relationship with won’t invest, they may talk to a friend about it who might.

The reverse of this notion is also true. If you get a bad reputation in the Wealthy community then you’re likely to find it very hard to raise funds for your next film.

4. Understand that most people with money will have other investment options.

As stated above, film investment is highly volatile and inherently risky. If these investors took on every potential project that comes asking for their money, they would not be rich for very long. As such, you’re going to have lots of competition when it comes to raising funds for your film. This competition will not only come from other films, but also from stocks and bonds, other startups and small businesses, and even the notion that if they’re going to spend 100k they never get back, why not just buy a new Mercedes?

5. Find a not entirely monetary way to close the deal.

So to bring the last point home, you have to find other reasons that aren’t solely based on return on investment to get people to consider investing in your independent film. This can be the tax incentives, the moral argument to support culture, the fact that investing in a film is an inherently interesting thing to do, or a few other potential things. The blog below explores this in much more detail than I have the time or the word count to do here today.

Related: Why Don't Rich Tech People Invest in Film Part 5: Diversification and Soft Incentives

If you still need help financing your film, you should check out my free indiefilm business resource package. It’s got lots of tools and templates to to help you talk to distributors and investors, as well as a free-ebook so you can know what you need to know to wow them when you do. Additionally, you’ll get a monthly content digest to help you stay up to date on the ins and outs of the film industry, as well as be the first to know about new offerings and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media. Get it for free below.

The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Finance (And Where to Find the Money)

Financing a film is hard. It might be easier if you break it up into more manageable raises. Here’s an outline on that process.

Most of the time filmmakers seek to raise their investment round in one go. A lot of people think that’s just how it’s done. As such, they ask would they try anything else. If you have a route into old film industry money you can go right ahead and raise money the old way. If you don’t, you might want to consider other options.

Just as filmmakers shouldn’t only look for equity when raising money, Filmmakers should consider the possibility of raising money in stages. Here are the 4 best stages I’ve seen, and some ideas on where you can get the money for each stage.

1. Development

If you want to raise any significant amount of money, you’re going to need a good package. But even the act of getting that package together requires some money. So one solution to getting your film made is to raise a small development round prior to raising a much larger Production round.

If you want to do this with any degree of success, you’re going to have to incentivize development round investors in some way. There are many ways you can do it, but they fall well beyond my word count restrictions for these sorts of blogs. If you’d like, you can use the link at the end of the blog to set up a strategy session so we can talk about your production, and what may or may not be appropriate.

Related: 7 Essential Elements of an IndieFilm Package

Most often, your development round will be largely friends and family, skin in the game, equity, or crowdfunding. Grants also work, but they’re HIGHLY competitive at this stage.

Books on Indiefilm Business Plans

2. Pre-Production/Production

It generally doesn’t make sense to raise solely for pre-production, so you should raise money for both pre-production and principal photography. This raise is generally far larger than the others, as it will be paying for about 70-80% of the total fundraising. It can sometimes be combined with your post-production raise, but in the event there’s a small shortfall you can do a later completion funding raise.

It’s very important to think about where you get the money for the film. You shouldn’t be looking solely at Equity for your Raise. For this round, you should be looking at Tax incentives, equity, Minor Grant funding if applicable, Soft Money, and PreSale Debt if you can get it.

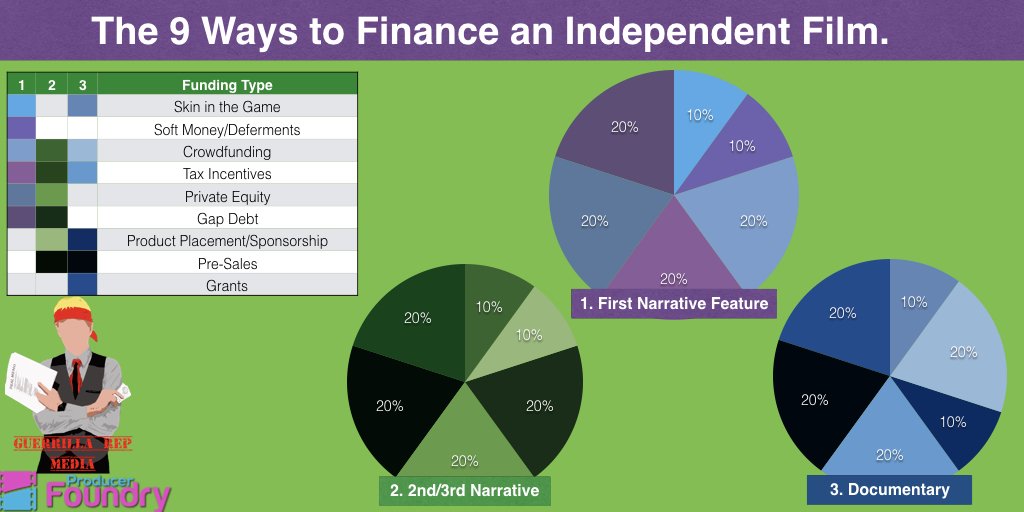

Related: The 9 Ways to Finance an Independent Film

Post Production/Completion

Some say that post-production is where the film goes to die. If you don’t plan on an ancillary raise, then too often those people are right. Generally you’ll need to make sure you have around 20-25% of your total budget for post. It’s better if you can raise this round concurrently with your round for Pre-Production and Principle Photography

The best places to find completion money are grants, equity, backed debt, and gap debt

4. Distribution Funding/P&A

It’s very surprising to me how difficult it is to raise for this round, as it’s very much the least risky round for an investor, since the film is already done.

Theres a strong chance your distributor will cover most of this, but in the event that they don’t, you’ll need to allocate money for it. Generally, I say that if you’re raising the funds for distribution yourself, you should plan on at least 10% of the total budget of the film being used for distribution.

Generally you’ll find money for this in the following places. Grants, equity, backed debt, and gap debt.

If you like this article but still have questions, you should consider joining my email list. You’ll get a free e-book, monthly digests of articles just like this, segmented by topic, as well as some great discounts, special offers, and a whole section of my site with FREE Filmmaking resources ONLY open to people on my email list. Check it out!

The 7 Essential Elements of A Strong Indie Film Package

If you want to get your film financed by someone else, you need a package. What is that? Read this to find out.

Most filmmakers want to know more about how to raise money for their projects. It’s a complicated question with lots of moving parts. However, one crucial component to building a project that you can get financed is building a cohesive package that will help get the film financed. So with that in mind, here are the 7 essential elements of a good film package.

1.Director

As we all know, the director is the driving force behind the film. As such, a good director that can carry the film through to completion is an essential element to a good film package. Depending on the budget range, you may need a director with an established track record in feature films. If you don’t have this, then you probably can’t get money from presales, although this may be less of a hard and fast rule than I once thought it was.

Related:What's the Difference between an LOI and a Presale?

Even if you have a first-time director, you’ll need to find some way of proving to potential investors that they’ll be able to get the job done, and helm the film so that it comes in on time and on budget

2. Name Talent

I know that some filmmakers don’t think that recognizable name talent adds anything to a feature film. While from a creative perspective, there may be some truth to that, packaging and finance is all about business. From a marketing and distribution perspective, films with recognizable names will take you much further than films without them. I’ve covered this in more detail in another blog, linked below.

Related: Why your Film Needs Name Talent

Recognizable name talent generally won’t come for free. You may need a pay-or-play agreement, which is where item 7 on this list comes in handy.

3. An Executive Producer

If you’re raising money, you should consider engaging an experienced executive producer. They’ll be able to help connect you to money, and some of them will help you develop your business plan so that you’re ready to take on the money when it comes time to. A good executive producer will also be able to greatly assist in the packaging process, and help you generate a financial mix.

Related: The 9 Ways to finance an Independent Film.

I do a lot of this sort of work for my clients. If you’ve got an early-stage project you’d like to talk about getting some help with building your package and/or your business plan I’d be happy to help you to do so. Just click the clarity link below to set up a free strategy session, or the image on the right to submit your project.

4. Sales Agent/Distributor

If you want to get your investors their money back, then you’re going to need to make sure that you have someone to help you distribute your independent film. The best way to prove access to distribution is to get a Letter of Intent from a sales agent. The blog below can help you do that.

Related: 5 Rules for Getting an LOI From a Sales Agent

5. Deck/Business Plan

If you’re going to seek investors unfamiliar with the film industry, you’re going to need a document illustrating how they get their money back This can be done with either a 12-slide deck, or a 20-page business plan. I’ve linked to some of my favorite books on business planning for films below.

6. Pro-Forma Financial Statements

Pro forma financial statements are essentially documents like your cash flow statement, breakeven analysis, top sheet budget, Capitalization Table, and Revenue Distribution charts that help you include in the latter half of the financial section of a business plan.

There’s a lot more information on these in the book Filmmakers and Financing by Louise Levinson. I’m also considering writing a blog series about writing a business plan for independent film. If you’d like to see that, comment it below.

7. Some Money already in place

Yes, I know I said that you need a package to raise money, but often in order to have a package you need to have some percentage of the budget already locked in. Generally, 10% is enough to attach a known director and known talent. If you’re looking for a larger Sales Agent then you’ll also need to have some level of cash in hand.

This is essentially a development round raise. For more information on the development round raises, check out this blog!

Thanks for reading, for more content like this in a monthly digest, as well as a FREE Film Market Resources Package, check out the link below and join my mailing list.

Check the tags below for related content.

Filmmakers! - 5 Steps to Successful Grantwriting

People say grant writing is hard, but it’s more straightforward than you think. Here’s a primer.

A few months ago I worked with the absolutely lovely Joanne Butcher of Filmmaker Success to put on an educational event about grant writing here in San Francisco. Joanne has raised millions in grant funding for several non-profits over the course of her life. While I can’t distill everything from her talk into a single blog, I can give the people who weren’t able to make it some of the key takeaways. So without further ado, here are the 5 rules for applying for grants.

1. Research

This might just be a Guerrilla Rep Media Rule of life at this point. If you understand the field you’re playing on, you’re going to be much better at whatever game you’re going to play there. The only way you understand that field is by researching it. But I digress.

When applying for grants, the first step is to research and find grants to apply to. (Duh) Focus on grants that match the subject matter of your film. It’s best to only apply for grants you’re perfect for, even if they are not directly related to filmmaking.

The fact is that no one can apply to the thousands of grants they are eligible for is why limiting to the perfect matches is going to greatly increase your success. It’s almost always a bad idea to bend something to fit a grant application. The key here is to remove the mindset of scarcity, and instead focus on finding the right fit.

As an example, if we were looking for funding for a reboot of The Little Mermaid, Joanne would recommend looking into marine science foundations, climate change foundations, and local artist grants, local filmmaking grants, or since it’s based on a Hans Christian Andersen book, even Denmark’s Cultural heritage foundations might be worth applying to.

This article is a good place to start for your research.

2. Set a goal for applications

Set an achievable goal for grants you want to apply for. A safe bet is one per month. This would put applying for grants as a heavy part-time job for you though.

It can be hard to find relevant grants to apply to get up to 1 per week, so you should consider applying to grants that are thematically related to your content, as opposed to strictly applying for film grants. What I mean by this is if your film is about homelessness, then maybe apply for grants from organizations helping the homeless, stating how you can help increase the awareness and impact of their foundation through the power of motion pictures.

3. Answer the Questions

Now that you’ve researched to find relevant grants, and you’ve set your goals, it’s time to start grant writing! I know that sounds super intimidating, but really it’s just answering a very long series of questions.

Although when you’re answering your questions, you should remember that it’s more than just providing information. Your goal here is to sell the grantor on why your project is the one that will get the most bang for their funders buck.

Every funder’s primary responsibility is to fund the projects that provide the most value to the foundation. Generally, this means the projects that get the most eyeballs on them, and offer the most benefits to the communities that particular funder serves. Your job is to convince that funder that your project is the one that will do that.

4. Hit Send

I know this sounds rather obvious, but once you’ve written your grant you need to press send. However, a lot of filmmakers get stuck at this step, and spend so much time perfecting their application that they either miss the deadline, or could have applied to a whole different grant in the time they spent making one of them about 2% better. Hit send, and start applying for the next one.

5. Apply Again Next Year

Finally, the first time that you apply for a grant, don’t be put off if you don’t get it.. Most funders get far more applications than they have money to fund, and competition is fierce.. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t apply, it just means that you need to keep applying, and, over time, improve both your proposals, your projects and your relationships with the funders. “After all, says Joanne, “you can’t apply a second time until you’ve applied for a first.”

IF you’re a filmmaker, you’re always likely to have some project that will require funding. Thus, relationships with funders will be very important to your long term career. By applying for film grants, you start to develop a relationship with the grantor, even if your grant applications are unsuccessful.

Also, if you’re declined, you can actually call up the funder, and ask why. Most times, grantors will share some insight as to why your application was declined. Doing this can put you in a much better position to get the grant next year. Just don’t be rude when you do; the point is to build a positive relationship

Thanks so much for reading! I’d heavily encourage you to check out Joanne Butcher’s website below. Also, check out the free indiefilm resource pack for EXCLUSIVE templates and tools to help you finance your film, as well as a monthly blog digest to help answer any questions that you may end up needing to fill out your grant proposal.

Check out Related content using the tags below

7 Reasons Courting an Investor is Like Dating

Closing investment for your film is all about your relationship with your investor. It’s weirdly like dating. Here’s why.

There’s an old adage that Investing is like Dating. In fact, I’ve talked about the similarities both on meetings with investors, and dates with people who are qualified to be investors. So as something of a tongue-in-cheek yet still (Mostly) safe-for-work post, here are 7 ways courting an investor is like dating.

1. Your goal is to see how compatible you are with the other person.

Most of the time, if you want to get into bed with someone, you want to be compatible with them first. Getting money from an investor isn’t like a one-night stand. You don’t just get the check and then never hear from them again. Getting into bed with an investor is a long-term deal, so making sure you two work well together is simply a must. Otherwise, the break-up may not be pretty.

2. If you come off as Asking for too much the first time out, you probably won't get a second.

The first time you go out with an investor is kind of like that first coffee date. you’re both sizing each other up, and you want to see how you click. If you went on a first date trying to make out and take the partner back to your place, it’s probably not going to end well for you. Similarly, if you start asking an investor to whip out their checkbook on the first meeting, then you’re not likely to get a call back for a second.

In summation, the goal of your first date should always be to get a second. If you’re out with an investor, then the second meeting is the sole goal of the first meeting.

3. It Generally takes at least 3-5 meetings to jump into bed together.

As with dating, it generally takes 3-5 meetings to decide to get into bed together. Often, the longer it takes the more likely it is that the relationship will be fruitful down the line. At least to a point. If it takes more than 7 meetings to get a check, the investor (or your romantic partner) might just want to be friends.

4. Both Parties have something to gain, but generally speaking one has significantly more options than the other.

Just like women are generally more sought after than men in the dating scene, Investors are generally more sought after than entrepreneurs. This may sound crass, but the only pretty girl in the room is going to get a lot more offers than the 10 guys pursuing her. The ratio is similar for investors.

So sure, while everybody is looking for a mate, and every investor needs deal flow, generally one side has more options than the other. It’s important to remember that when attempting to court an investor.

5. They're Probably going to Google You.

Everybody does diligence in this day and age. If you didn’t think your date was going to check out your online presence, you should probably think again. Investors are going to look into your past history, and maybe even check your credit before they invest in you. Dates will do as much as they can on a similar level, but probably not check your credit.

Related: 5 Steps for Vetting Your Investors

6. If you jump into bed on the first date, you're in for a wild ride. a

One-night stands can be fun and all, but if you jump into bed with the wrong person right after meeting them it can be a real nightmare. (Or so I’ve been told…) If you don’t take the time to get to know somebody before you get into a serious relationship with the, you’re going to be in for a nasty surprise. All investment deals are serious relationships. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

7. When you seal the deal, you might be stuck with that person for YEARS.

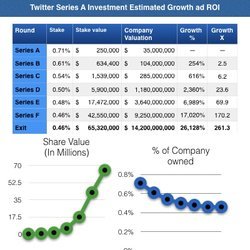

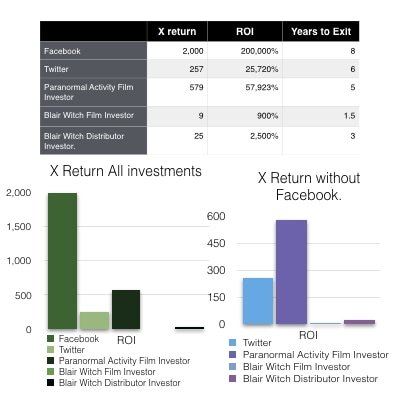

If you take money from someone you’ll be dealing with them until all investors somehow exit the company. This can be many years. The Series A Investors at Twitter didn’t exit until their IPO Years later, and a film generally takes 3-5 years to pay back their investors, if they ever do.

If you do get into bed with an angel investor to finance your feature film or web series, they’re going to be a part of your business for a long time. It’s not just about finding independent film angel investors, it’s also about courting them and making sure you’ve found the right investor, not just the first investor who makes you an offer.

If you want some help with this courting process, my free resource package is a great place to start. It’s got a free e-book that might answer some questions your investor may have. It’s also got a deck template you can use in your first meeting. Get it for FREE below.

Check out related content using the tags below.

Indiefilm Crowdfunding Timeline

In crowdfunding preparation is key, just as it is with filmmaking. If you want to succeed, you need to have a solid plan. Here’s a timeline that might help.

In crowdfunding as in filmmaking, preparation is key. If you don’t adequately prepare for your campaign, then you’re not likely to succeed. If you’ve never crowdfunded before, this can be a daunting prospect. Don’t worry, Guerrilla Rep Media is here to help. This post is meant to give you a timeline to prepare for your campaign, starting further out than you might think.

It’s based around what I’ve learned raising 33,000 of my own in the early days of kickstarter, as well as what I’ve learned from speakers and advising clients running their own campaigns.

6-12 Months Prior to Launch

Begin interacting with online and in-person communities relevant to your target market

If you want to have a chance at people outside of your friends and family donate to your crowdfunding campaign, then you’ll need to become a part of those communities early. If you show up and immediately start asking for money, you’re only going to lose friends and alienate potential backers and customers. If, on the other hand, you become part of the communities you’re targeting early on then you may well end up getting yourself some new audience members who might just back your campaign.

Related: 5 Dos and Don't for Selling your Film on Social Media

It’s a lot of work, but the benefits may surprise you. They’re likely to reach beyond your professional life, and into your personal life.

3 Months Prior To the Launch

Begin to be really active in groups of your target market.

Essentially, this is an extension of the list above. As your campaign approaches, spend more time engaging with people on those online communities you joined 3-6 months ago.

2 Months Prior to the Launch

Shoot Video

List All Potential Perks

Let People Know You'll be Running a Campaign

Get set up with your Payment Processor

About 2 months before your expected launch, you should get as much of the preparation out of the way as you can. This includes things like shooting your video, listing your potential perks, and potentially even getting set up with the payment processor of whatever platform you’re using.

Many of those things take much longer than you expect them to, so doing them early will make sure that your campaign launches smoothly.

1 Month Prior to Launch

Start seeing what press you can get.

Create a Facbook Event for Launch

Finalize list of Perks

Organize Launch Party

A month out from your campaign is when your pre-launch should be going into overdrive. You’ll need to issue a press release about your campaign to try to get some local press, make a Facebook event for the launch party to try to get some early momentum, finalize all your perks, and potentially organize a launch party to help get people excited about your project. You may want to consider making your launch party backer-only, just to get the numbers up early on. Let people donate at the door from their if you need to.

Related: Top 5 Crowdfunding Techniques

1 Week Prior to Launch

Do at least one press interview (if you can)

Promote Launch Day on Social Media

Confirm a few large donations to come in on lauch day: Ideally right at launch.

With your launch date less than a week away, you’ll want to see if you can get any press. This can be anything from a local newspaper from the town you grew up in, it could be a friend’s podcast, or it could even be some old high school alumni newsletter. The press will give you legitimacy and legitimacy means more backers.

While you’re doing this, you’ll want to spend a lot of time talking about the impending launch on social media and talking to some big potential donors about coming in in the first few hours of the campaign. If people see more traction early on, they’ll be more likely to jump on board.

Launch Day

Follow-up with AS MANY PEOPLE AS YOU CAN to get them to donate.

If you have some large confirmed donors, then you need to follow up with them and remind them on launch day. It matters a lot to get some big fish in right as the campaign starts.

First Few Weeks of the Campaign

INDIVIDUALLY email EVERYONE you can to ask them to donate.

Once you get your campaign started, you’ll want to INDIVIDUALLY email EVERYONE in your address book. I’m not talking about setting up and sending out a mail chimp email, I’m talking about individually reaching out to follow up with EVERYONE who you have an email for. One trick I’ve learned from a friend and Former Speaker Darva C. is that you should email 2 letters of the alphabet a day, over the first 2 weeks of the campaign. Then email them again, starting on day 16 of the campaign.

It’s a grind, but making a film always required sacrifice.

Midpoint of Campaign

Host an event to keep interested high.

It would be wise to have an event to keep your social media spirit high in the lull that is the midpoint of the campaign. You have to keep the momentum going through the campaign, so having something like a midpoint event to talk about on social media is incredibly useful. This event is one I would HEAVILY consider making backer-only, even if they’ve only backed you for 1 dollar. You could also let them back at the door from their phone.

Last Few Weeks of Campaign

Individually email everyone you can AGAIN.

Do the same thing that you did on the first 13 days of the campaign again. Thank the people who donated, and remind the people who didn't to donate again.

Closing Night-Host a celebration (or commiseration) party!

Finally, at the close of the campaign, you’ll need to have a party, whether to celebrate your success or commiserate that you didn’t hit your goal. Either way, you’ll deserve a night of fun because you WILL be tired.

If this seems like a lot, it is. Even once you’ve finished raising, you still need to make the movie. My free Film resource package includes a lot of resources to help you make it and get it out there once it’s done. It’s got a free e-book, lots of templates, and a whole lot more. Click the button below to sign up.

Click the tags below for more related content!

The 5 Rules to Running a Successful Crowdfunding Campaign

Like it or not, if you want to finance your first feature film, you’re probably going to need to crowdfund part of the budget. Here’s a guide to get you started.

Since my exit from Mutiny Pictures Most of my work, these days is as an executive producer, consultant, distribution representative, and marketer. However, there was a time when I was a filmmaker and a regular (as opposed to executive) producer. During that time, I raised a total of 33,000 on Kickstarter for two projects. This blog gives you some of what I learned from those two campaigns.

While those two projects never went as far as they could have due to a parting of ways between myself and my former business partner, there’s still a lot of information I learned in running these campaigns in the early days of Kickstarter. Here are 5 of them.

#1. Prepare

You CANNOT be successful in crowdfunding without preparation, and that preparation starts early. Generally, your soft preparation for a crowdfunding campaign will start at least 6 months before you launch your campaign. This soft preparation will consist more of being an active member of your community. About 3 months out you’ll need to get ready to shoot your video, and about 2 months later you’ll need to get ready for pre-launch.

I’ll be releasing a preparation timeline in a few weeks, so check back soon!

#2. Grow Your Network

About 80% of your donations will come from people you already know and interact with regularly. This is why you need to become active in communities that will be interested in your film. This can be alumni organizations, groups of people enthusiastic about the kind of film you’re making, and any other group of people that are tangentially connected to the film you’re planning on making.

#3. It’s a Full Time Job, Plan Accordingly

No matter how much preparation you do, when the campaign starts it will be at least one person’s full-time job. You’ll need to personally thank everyone who donates, and you’ll need to spend a lot of time emailing basically everyone you know individually. If you’re smart, you’ll do it twice. Bulk emails aren’t going to do you anywhere near as much good as individual emails, and individual emails take a lot of time.

#4. Try to Get as Much Press as Possible

The best way to add legitimacy to your campaign is to get mentioned in the press. In order to get that press you’ll need to reach out to any editors and reporters you can that might cover you. Note that I say editors and reporters THAT MIGHT COVER YOU. If you know a reporter at Variety, you probably don’t want to email them about your campaign since they’re not going to cover it. If you grew up in a small town with a local paper, you definitely do. You’d be surprised what they’ll cover.

This is something you can work with your prospective crew about as well. Maybe you’re not from a small town, but your DP or production designer might be. This can be a very mutually beneficial arrangement, it puts your crew in the spotlight and raises the profile of the film.

It would be wise to send out a press release via one of the many press release sites. This will help you generate at least a few articles on affiliates for NBC, FOX, and others that you can use to grow the profile and perceived legitimacy of your campaign. It also has some SEO benefits, but I’m not sure that would help too much on crowdfunding.

#5. DON’T SPAM

Don’t post your campaign incessantly on all of your social media, Make sure you continue to provide value outside of asking for money while you’re in your campaign.

If you use Messenger to send your campaign to someone, open up a conversation first. Don’t just copy-paste a form email with no conversation back from them.

Say hello to someone first. Ask how they’re doing. Then send them info about your campaign when they ask what you’re up to. Taking the time to show you care about what’s going on in their life will greatly increase both your conversion rate and the amount each member of your network contributes.

Thanks for reading! If you like this, you should go ahead and grab my FREE Film Market Resource Pack. It’s got a free e-book of articles like this one to help you grow your filmmaking career, free templates to streamline investor and distributor conversations, and even a monthly content digest that helps you continue to grow your knowledge base on a schedule that’’s manageable to almost anyone. Get it for FREE Below.

4 Reasons Niche Marketing is VITAL to your indiefilm’s Succes

If you want to grow your career in entertainment, it’s all about audience. If you want a big audience, you need to start with die hard fans. That means you’ve got to know your niche.

Most people don’t plan to fail, they simply fail to plan. Similarly, most filmmakers don’t think about anything other than getting the film made until the film is completed. This is a prime example of failure to plan resulting in a failed project. In reality, you should be thinking about your target market as early as when you write your script. If this is your first film, you should be targeting a well defined niche. Here are 4 reasons why.

Would you Rather Watch than Read? Here's a video on the same general topic from my YouTube Channel.

Niche Marketing Gives you an audience for your film

I’m sorry to be the one to tell you this, but your film is unlikely to appeal to everyone everywhere. You’re much better off figuring out what parts of your story will resonate with various groups, and focusing your early marketing efforts on them. It will put your film in front of the people who it will resonate most strongly with, and it will help you rise about the white noise that every content creator must face, especially when starting out.

It’s also important to keep in mind that just because your film starts in a niche doesn’t mean that the niche is where it will always live. If you properly utilize niche marketing, it can actually help you break out of the niche and into the more generalized marketplace.

Niche Marketing Cuts down on your marketing cost

If you do think that you can target everyone, because your film is just that universally appealing then your marketing expenditures are going to be astronomical. Also, you’ll be competing directly with movies like Star Wars, The Avengers, and whatever the next Pixar movie is. Unless you’re a studio head, then you can’t afford to win that competition.

Utilizing proper niche marketing efforts will dramatically cut down on your marketing expenditure since you’ll know exactly who you want to get your project in front of. Thanks to social media platforms, you’ll be able to target those people directly using smart advertising buys and strong community engagement from an early stage.

Further, if you do break out of your niche, you’ll already have more noise being made about your project so the costs to market it will be much smaller.

Niche Marketing Can help you fund your film

If you start to get involved in niche communities well before you make your film, then you’ll have a community that you can mobilize to help you raise a portion of your funding through donation-based crowdfunding. To be clear, if you simply post your campaign over and over to the various communities you want to support your campaign. You’ll have to ingratiate yourself into them well before starting a campaign.

The Reason that these people may well be willing to support your campaign is that many niche communities are underserved, and want to have their story shared.

They want to see more media made about their interests and themselves as a community. They want their story told. Many of them, are willing and eager to make it happen. This brings us to our final point.

Niche Marketing Gives you advocates for your film

No Films can market themselves completely on their own. They need to get a core group of people to help spread the word. Niche marketing can be a huge help for getting the people who are most likely to be your strongest advocates onboard early. As mentioned above, they’re the people who care the most about your subject matter. They’re the people who will seek out your content and show it to your friends because they identify with it so much.

No one can create advocates, you must find them. The most likely place to find them is within the various underserved niches that have plenty of stories that need to be told.

Thanks so much for Reading. If you like this and want more, check out my FREE Film Business Resource Pack! You’ll get a free e-book on the business of entertainment, a set of highly useful templates, and a whole lot more. Check it out below.

The Two Main types of Financial Projections for an IndieFilm

If you’re seeking investment for your movie, you need to know how much it will make back. Here are the 2 primary ways to do that.

As a key part of writing a business plan for independent film, a filmmaker must figure out how much the film is likely to make back. This involves developing or obtaining revenue projections.

There are generally two ways to do this, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The first way is to do a comparative analysis. This means taking similar films from the last 5 years and plugging them into a comparative model to generate revenue estimates. The second way is to get a letter of intent from a sales agent and get them to estimate what they could sell this for in various territories across the globe.

This blog will compare and contrast these two methods (Both of which I do regularly for clients) in an effort to help you better understand which way you want to go when writing the business plan for your independent film.

Would you Rather Watch/Listen to this than read it? Here’s a corresponding video on my YouTube Channel!

Comparative Analysis - Overview

A comparative analysis is when you comb IMDb Pro and The-Numbers.com to come up with a set number of comparable films to yours. These are films that have a similar genre, similar budgets, similar assets, are based on similar intellectual property, and are generally within the last 5 years. If you can match story elements that are a plus, but there are only so many films with the necessary data to compare.

When I do it, I compare 20 films, average their ROIs from theatrical, pull numbers from home video wherever I can (Usually the-numbers.com), and then run them through a model I’ve developed to come up with revenue estimates. Honestly, I don’t do a lot of this work. Most of the time I refer it to my friends at Nash Info Services since they run The-Numbers.com and the brand behind these estimates means a lot to potential investors.

I will do it when a client asks though, generally as a part of a larger business plan/packaging service plan.

Sales Agency Estimates - Overview

Sales Agency Estimates are when you get a letter of intent from a sales agent, and as part of that deal the sales agent prepares estimates on what they think they can sell the film for on a territory-by-territory basis. Generally, they work from what buyers they know they have in these territories, whether or not they buy content like this, and what they normally pay for content like yours.

These estimates are heavily dependent on the state of your package, who’s directing your film, and who’s slated to star in it. If you don’t have much of a package and a first-time director, then you’re not going to get very promising numbers.

Comparative Analysis - Benefits

Generally, anyone can get these estimates. Some people figure out the formula and do it themselves, others pay someone like me or Bruce Nash to do it for them. There’s either a not insubstantial fee involved or a lot of time involved in getting them. They’ll generally satisfy an investor, especially if Bruce does it.

Sales Agency Estimates - Benefit

The biggest benefit to a sales agency approach is that if they’re doing estimates for you, they’re probably going to distribute your film. Also, these estimates have the potential to be more accurate, because they’re based on non-public numbers on what buyers are paying in current market conditions. Finally, if a sales agent has given you an LOI, these estimates are generally free.

Comparative Analysis - Drawbacks

The first drawback is likely that they’re either very time intensive or somewhat costly to produce. Also, because VOD Sales data is kept under lock and key, it’s very difficult to estimate total revenue from VOD using this method. Given how important VOD is, that’s a somewhat substantial drawback.

Further, these estimates are greatly helped by the name value of who made them. Likely, if the filmmaker makes them themselves, then they’re not as viable as if someone like Bruce or Me does them. This is not only because we both have a track record in them, (Bruce much Moreso) but also because we’re mostly impartial third parties.

These revenue estimates can be very flawed if a filmmaker makes them because many filmmakers have a tendency to only pick winners, not the films that lost money. In business, we call this painting too blue a sky, as it makes everything look sunny with no chance of rain. In film, there’s always a substantial chance of rain.

Sales Agency Estimates - Drawbacks

The biggest drawback to these estimates is that not everyone can get these estimates. You have to have a relationship with the sales agency for them to consider giving them to you. Generally, you’ll need to have convinced them to give you an LOI first. That’s not always the case though.

If you have a producer’s rep, they can sometimes get you through the relationship barrier, but they’ll often charge for doing so when we’re talking about a film that’s still in development.

Also, Sales agencies can sometimes inflate their numbers to keep filmmakers happy and convince them to sign. This does not look good to investors if that money never comes in

Conclusion

Overall, which method you use to estimate revenue depends entirely on what situation you find yourself in. If you have the ability to get the sales agency estimates, they can be VERY strong, if you don’t, the comparative estimates are reliable enough to do what you need them to do. That being said, I wouldn’t advise taking a comparative analysis to a sales agency.

Thanks for Reading! Creating revenue estimates is only part of raising money for your film. There’s a lot more you’ll need to know if you want to succeed. That’s a large part of why I created my indie film resource package, to help filmmakers get the knowledge and resources they need to grow their careers. It’s totally free and has things like a deck template, free e-book, and even specialized blog digests sent out on a monthly basis to help you understand how to answer the questions your investors will almost certainly have. Check it out at the button below.

Get more related content through the tags below.

7 Realistic ways to Find First Money In on your Feature Film.

The first money in is always the hardest to raise. Here’s a guide of realistic sources you can actually raise for your feature film.

When fundraising for anything, the first money is always the hardest. Investors don’t want to be the first in due to the investment seeming untested. So in order for them to feel more secure, you might need to raise some of the money in other places. Here are the 7 most realistic places for filmmakers to go to get first money in.

First money in isn’t meant to be the entirety of your budget. It’s only meant to be about 10%. Having raised 10% of your budget helps investors see that you’re serious, and aren’t going to require them to do all of the funding work themselves. With that in mind, almost every item on this list is not meant to fund your entire movie, but more serve as a jumping-off point to help you raise the funds you need to make an awesome film.

Highly Related: The 9 ways to Finance your Independent Film

1. Donation based Crowdfunding

I know most filmmakers really don’t want to hear about crowdfunding, but it’s still one of the best ways to serve as a proof of concept for a film. It’s also a great way to get first money in. Specifically for this example, I’m talking about donation based crowdfunding. I’m far from an expert in equity crowdfunding, and while there’s potential in the idea, it’s unclear how it should be executed.

That being said, donation based crowdfunding can be an excellent way to get the project rolling, and get further into development.

2. Tax Incentives

Depending on where you’re planning on shooting, Tax incentives can be a great way to get a portion of your funding in place. If you’re in the US, then shooting in Kentucky can get you as much as 35% of your budget. Granted, that will go down to about 30% once you take out a loan against it so that it becomes real money instead of a letter of credit. That loan will be fairly low interest, since Kentucky’s incentive is structured as cash.

There are a lot of things I could go into about tax incentives, but it’s more than I can cover in this blog. I might make a future blog or video about it Comment and ask.

3. Grants

There aren’t a lot of development stage grants out there, and as such the few there are tend to be in very high demand. However, if you can get some portion of you money via a grant from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation or some other development stage granter, then it cuts the risk for your investors and gives you first money in.

Keep in mind, most organizations that give grants turn you down automatically when you first apply. It can be wise to apply multiple years in a row while you try to get this film, or other films off the ground.

4. Equipment Loans

An equipment loan is a relatively low interest loan that uses any equipment you own as collateral for the money that’s being lent. I understand that this is a scary prospect for many filmmakers (With good reason) but it can be a way to get money into the project at an early stage, and serve as your first money in.

It’s also important to note that debts are paid off before equity is paid back, so your loan would be repaid and your equipment secured before any future investor got their money back. Of course, this isn’t always the case, but it generally is.

5. Personal or Business Credit

There are a few people who will loan money for films based on your personal credit. Sometimes it will be a business loan, sometimes it will be an insanely high limit credit card, but in the end it can be the money you need for development. It’s not ideal, but it can be a way to get your movie to the next level.

If you’ve been making corporate videos through your entity for a number of years your business may have enough credibility to take out a moderaate interest loan from a bank against your future corporate video earnings.

In general, this will be a percentage of your previous earnings according to you last few tax returns and whatever debt burden the business has from general operations. This is best used to offset time away from corporate work as an expansion into a new product line, I.E. your feature film.

This would most likely be considered an unsecured loan, which means it’s higher interest than the equipment loan or anything of the sort like that.

If you do go down this road, you should not forget that it often takes 12 to 18 months from delivery to a distributor to start earning royalties, and that’s not accounting for the minimum of 9-12 months to make the film and deliver it to a distributor. The interest over the course of a term like that might be hard to bear.

I should stress I’m not a lawyer or financial advisor. You should check with yours before acting on anything on this list, especially anything that’s debt base.

6. Wealthy Friends and Family

If you’re lucky enough to have accredited investors in your friends and family, then this can be a good way to get your first money in. Investors normally invest in people as much if not more than projects, so approaching someone you already know is generally an easier ask than someone you don’t. Since this blog is about getting first money in, having an investment from a wealthy friend or relative can be the quickest and easiest way to get over that hurdle.

Of course, in order to raise money from wealthy friends and family, you must HAVE wealthy friends and family. If your friends and family ARE NOT Accredited investors, then it’s best to include them in a donation-based crowdfunding round. While the SEC (Securities and Exchanges Commission) has loosened requirements for high-risk and small business investments since the JOBS Act, they’re still very strict when it comes to high risk investments, and it would be better for you to not run afoul of them.

7. Equity Investment

Finally, if you don’t have wealthy friends and family, you can chase equity investment. Normally this means that you would approach the person who owns the car dealerships in your neck of the woods, or other local business leaders. If you can get a meeting to talk to them about investing in a movie, there’s a chance that the excitement of it might help you raise a portion of your funding.

Mind you, this is not an easy sale. It’s going to take a skilled salesperson to pull it off, and a lot of research into why someone like this person who owns the car dealerships would want to invest in your project.

Thank you for reading! If you found this content valuable, check out my FREE film business resource pack. It’s got a free e-book on the indiefilm biz featuring 21 articles around similar issues covered in my blog. Around half of those articles can’t be found anywhere else. Additionally, you’ll get an indiefilm deck template you can use to create a deck for investors, contact tracking templates, form letters, and a whole lot more! Check it out below.

5 Steps to Vetting your investor

Not everyone is who they say they are, and not everyone who says they’ll fund your movie actually can. Here’s how you vet your investors.

Just like all filmmakers and Entrepreneurs are not created equal, nor are all “Rich Guys.” Many will jerk you around, and not actually deliver on what they promise. So how do you know if your potential investor is legit? Well, here are a few tips.

Note: This Article is largely in response to a piece by Jason Brubaker at Filmmaking stuff. Overall it’s a good piece, but I felt it lacking a few things so I’m expanding it with my thoughts. You can find the original article here. Even though Jason was a bit too involved with Distribbr and that whole debacle, he did make some good content so my response blog is getting a port.

Look them up online (Duh)

You need to know who you’re dealing with, so before you meet with them you should do some diligence. The goal of this step is just to ensure they have money, and get an idea of whether they’ll be likely to spend it.

You want to find out what they’ve done, and where they got their money. Generally start by looking them up on AngelList and Slated. These sites do some pretty deep vetting for to make sure that investor members are accredited. They’ll also list the previous investments of the investor, so you can see how they stack up against yours.

Slated is strictly for film, AngelList is focused on Tech. If they have active profiles on these sites, then you know that they are active investors. Active investors are more likely to invest.

If they don’t have either of those profiles, look at their LinkedIn. Generally Linkedin will show you previous positions, if they have multiple executive positions at companies with more than 15 employees, or list that their company was sold to a bigger company they probably have excess capital to invest.

If you’re too far away from them to see their full Linkedin profile, google them. If they have a profile in Forbes or Bloomberg, you’re set. If they have a ton of lawsuits or if you find something saying they, I Don’t Know, tried to buy a baseball team but were laughed out of the room then lambasted by a major newspaper, maybe steer clear. Totally not at all a real example, by the way.

2.Look at what they’re wearing and what they’re driving.

As Brubaker says, this technique is far from perfect. Sometimes the guy in the three-piece suit has less capital than the girl in the jean jacket and yoga pants. However, there are some things you can take into account. Fashion is highly dependent on the area you live in. Here in Silicon Valley, it’s common for the people in sweats to be worth more and be more likely to invest than the suits. Try to understand the cut of the clothes, and get an eye for designers. I know some people who wear T-shirts that cost more than I paid for my first Armani suit. Admittedly, I bought that suit secondhand.

But there are some constants. Before you look at the clothes, look at the shoes. People, especially men, overlook the importance of shoes to the overall aesthetic, but they’re a relatively constant indicator of wealth. Watches are also a good indicator of status.

Whatever make or model of car they drive will give you a good idea of how much they’re worth. Generally make is better than model, for example, hybrids are big here in the bay. for a time, a Prius was a status symbol. Now that most luxury brands have a hybrid, the make is generally a good metric to judge by. Teslas are still a great indicator.

3.Do they pick up the check?

Here’s one that I totally disagree with Jason on. He makes the point that if he can’t pick up a 50 check you’re not getting a 50,000 dollar check from them. Whether or not an investor picks up the check is largely dependent on a few factors. If they’re an independent angel investor, they can take about 8 meetings with entrepreneurs a week. If they always picked up the check, they wouldn’t be an accredited investor for long. Also, most of the rich guys I know are surprisingly stingy.

Generally, if it’s a first meeting I split the check. I pay for my seat at the table, they pay for theirs. A fear of many legitimate angel investors is whether or not the entrepreneur is going to carry their weight, so in a way splitting the check is symbolic of what a good relationship with an investor should be. Future meetings are up for debate.

4. If they’re talking about “Money Coming In” it’s BS.

Jason is completely correct on this one. Unless the startup they were one of the first ten employees at a is about to IPO, (You can google that, and easily fact-check it) that money won’t come in.

However, if they say their money is tied up, that’s a different story. Savvy Rich people don’t let their money sit in a checking or savings account. They invest it. Most of the time, they’ll have a respectable stock portfolio. That means they’ll have to sell something (Liquidate Assets) in order to free up money to invest in your projects. Here’s a tool to help them to do that.

5. Is it too Easy?

It may sound counterintuitive, but if it’s too easy to get the check that should be a huge red flag. I’ve worked in Silicon Valley and Hollywood, and it’s never easy. It requires finesse, charisma, and luck. Just like you need to do your homework, your investors need to do homework on you. They will need a deck, a business plan, and a good relationship in order to give you a check.

This analogy is crass, but the more I play this game the more I realize the truth behind it. Getting investment is like dating. You have to get to know each other first. Then you figure out if you like each other you figure out if you could work well together. Finally, after 3–7 excellent meetings and more phone calls and messages, you get into bed together. Often the more meetings it takes to get into bed, the better the relationship will be. That’s not always the case though.

If you want more like this, you should grab my free film market resource package. It’s got lots of templates to help you talk to investors and distributors including deck templates form letters, and tracking sheets as well as money-saving resources and a free e-book.

Check out the tags below for similar content!

The 9 Ways to Finance an Indiependent Film

There’s more than one way to finance an independent film. It’s not all about finding investors. Here’s a breakdown of alternative indie film funding sources.

A lot of Filmmakers are only concerned with finding investors for their projects. While films require money to be made well, there’s are better ways to find that money than convincing a rich person to part with a few hundred thousand dollars. Even if you are able to get an angel investor (or a few ) on board, it’s often not in your best interest to raise your budget solely from private equity, as the more you raise the less likely it is you’ll ever see money from the back end of your project.

Would you Rather Watch or Listen than Read? I made a video on this topic for my YouTube Channel.

So here’s a very top-level guide to how you may want to structure your financial mix. The mixes in the image above loosely correspond to the financial mix of a first-time film, a tested filmmaker’s film, and a documentary. They’re also loose guidelines, and by no means apply to every situation, and should not be considered financial or legal advice under any circumstance. This is just the general experience of one Executive producer.

Piece 1 — Skin in the game. 10–20%

Investors want you to be risking something other than your time. The theory is that it makes you more likely to be responsible with their money if you put some of yours at risk. This can be from friends and family, but they prefer it come directly from your pocket.

I've gotten a lot of flack for this. However, the fact investors want skin in the game is true for any industry or any business. Tech companies normally have skin in the game from the founders as well, not just time, code, or intellectual property.

However, if you’ve got a mountain of student debt and no rich relatives, then there is another way…

Piece 2 — Crowdfunding 10–20%

I know filmmakers don’t like hearing that they’ll need to crowdfund. I understand it’s not an easy thing to do. I’ve raised some money on Kickstarter and can verify that It’s a full-time job during the campaign if you want to do it successfully. However, if you can hit your goal, not only will you be able to put some skin in the game, and retain more creative control and more of the back end but you’ll also provide verifiable proof that there’s a market for you and your work. Investors look very kindly on this.

That said, just as success provides strong market validation as a proof of concept, failing to raise your funding can also be seen as a failure of concept. and make it more difficult to raise than it would otherwise have been. Make sure you only bite off what you can chew.

Due to the difficulty in finding money for an independent film, the skin in the game or crowdfunding portion of the raise for a director’s first project is often a much higher percentage of the raise than it will be for their future projects.

Piece 3 — Equity 20–40%

Next up is equity. This is when an investor gives you money in return for an ownership stake in the company. From a filmmaker's perspective, it’s good in that if everything goes tits up, you don’t owe the investors their money back. Don't misunderstand what I mean by this. You ABSOLUTELY have a fiduciary responsibility to do your due diligence and act in the best interest of your investors to do absolutely everything in your power to make it so they recoup their investment. If you do that, or if you commit fraud, your investors can and likely will sue the pants off of you. You’ll have an uphill battle on that as well since they probably have more money for legal fees than you do.

Also, you will need a lawyer to help you draft a PPM. You shouldn't raise any kind of money on this list without a lawyer, with the possible exception of donation-based crowdfunding or grants. In general, just remember that I’m a dude who produced a bunch of movies who writes blogs and makes videos on the internet. Not a lawyer or financial advisor. #Notlegaladvice #Notfinancialdvice #mylawyermakesmewritethesesnippets.

It’s bad in that if everything goes extremely well, they get a huge percentage of your film. So it deserves a place in your financial mix, but ideally a small one.

For a longer list of my feelings on this topic, check out Why film needs Venture Capital, or One Simple Tool to Reopen Conversations with Investors

Piece 4 — Product Placement 10–20%

Product placement is when you get a brand to compensate you for including their product in your film. It’s more common in the form of donations or loans for use than hard money, but both can happen with talent and assured distribution. If you’re a first-timer, it’s difficult to get anything other than donated or loaned products.

Piece 5 — Presale Backed Debt 0–20%

Everything you read tells you the presale market has dried up. To a certain degree, that is true. However, it’s more convoluted than you may think. According to Jonathan Wolfe of the American Film Market, the presale market has a tendency to ebb and flow with the rise and fall of private equity in the filmmaking marketplace. There’s been a glut of equity for the past several years that’s quickly drying up.

That said, there are a lot of other factors that will determine where pre-sales end up in a few years. The form has shifted, in that it’s generally reputable sales agents that give the letters instead of buyers and territorial distributors. You then take that letter to a bank where you can borrow against it at a relatively low rate.

Piece 6 — Tax incentives 10%-20%

While many states have cut their filmmaking tax incentives, it’s still a very viable way to cover some of the costs of making your project. It is worth noting that the tax incentive money is generally given as a letter of credit, which you can then borrow against or sell to a brokerage agency. It’s not just a check from the state or country you’re shooting in. This system of finance is significantly more viable in Europe than it is in the US, but no matter where you plan on shooting it needs to be part of your financial mix.

Piece 7 — Grants 0–20%

There are still filmmaking grants that can help you to make your project. However, that’s not something that is available to all filmmakers, especially when they’re first making their projects. Don’t think grants don’t exist for you and your project, because they probably do, spend an afternoon googling it. My friend Joanne Butcher of www.FilmmakerSuccess.com suggests applying for one grand a month for the indefinite future, as when you do so you’ll develop relationships with the foundations you contact which can be invaluable for your career growth.

Grants are much easier to get as a completion fund once you’ve shot your film. Additionally, films made overseas are more likely to be funded by grants than those shot here in the US.

Piece 8 — Gap/Unsecured Debt 10–40%

Gap debt is an unsecured loan used to create a film or television series. This means that the loan has no collateral, be it product placement, Presale, or tax incentive. It used to be handled by entertainment banks for a very high interest rate, I can’t say who my source was on this, but I have heard of interest rates in excess of 50% APR. That market has been largely taken over by private investors loaning money through slated, which did bring interest rates down. Unsecured debt almost certainly requires a completion bond, which generally means that it’s only suitable for projects over 1mm USD in budget.

In general, you should use this form of financing as little as possible, and pay it back as quickly as possible. Again, Not legal or financial advice.

Piece 9 — Soft money and Deferments — whatever you can

Soft money is funding that isn’t given as cash. This can be your crew taking deferred payment for their services, or receiving donated or loaned products, locations, and anything else meant to get your film made. This isn’t so much funding as cost-cutting. It often includes donations or loans from product placement.

If you like this content and want to learn more about film financing, you should consider signing up for my mailing list. Not only will you a free e-book, but you’ll also get a free deck template, contract tracking templates, and form letters. Plus you’ll stay in the know about content, services, and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media.

How do we Get More Investors into Independent Film?

How do we get more investors in the film industry? We improve the viability of film as an asset class. Here’s how.

Throughout writing this blog series, I’ve been told more times than I can count that film is a terrible investment, and no one besides hobbyists would consider it. Many want to leave it there, without bothering to look at what’s causing it. Last week we thoroughly examined the issues plaguing the film industry, and what keeps investors out. The issues aren’t pretty, but they may be fixable. What follows is a list of what could be done to fix this problem and some of the ways organizations that are implementing these tactics.

Greater Transparency

One of the biggest things stopping film investment is the perception that it’s unprofitable. All too often that’s not simply a perception. Another thing stopping independent film as an industry from being profitable is the fact that many sales agents don’t accurately report the earnings of the films they represent. Others charge too much in recoupable expenses, so it’s unlikely to recoup. Some take an unreasonable portion of the revenue or simply hide sales from filmmakers.