Why You Still Need Name Talent in Your IndieFilm

If you don’t think having recognizable names in your film will help you grow your career, you’re wrong. Here’s why.

In the age of easily accessible self-distribution, cheap gear, and the ability to make and distribute a feature film for less than 10,000 dollars it’s understandable to wonder why you would want to spend 10,000-100,000 dollars a day on recognizable name talent. Many proclaim that hiring recognizable name talent is simply a waste of time and money.

Speaking as someone who makes most of their living from film distribution, these people are wrong. Here are 5 reasons why.

Recognizable Name Talent Significantly increases the Profile of the Film

In an age where anyone can make a film, the challenge becomes less one of making a film, and more one of rising above the white noise created by others also making films. Recognizable name talent can be a great help you set yourself apart. The notoriety brought by recognizable name talent helps raise public awareness of your project and greatly increases interest from high profiles sales agents and distributors. Also, if they have a large social media presence and agree to help promote your film, it will have a tangible impact on the profile of your film.

Recognizable Name Talent Significantly increases the chance of meaningful press coverage.

With the higher profile that names talent brings to your project. Press coverage will compound the impact on the awareness of your film that name talent brings. If your film gets enough coverage, then a lot of the marketing will be done for you, and you’ll be able to attract the pieces of the puzzle that you’d otherwise need to chase. These puzzle pieces can be anything from additional tickets sold, to in-kind product placement, and potentially even completion funding once your film is in the can.

Several of my pre-completion press articles have been due in large part to having recognizable names attached to the project.

Recognizable Name Talent Increases the likelihood of getting into festivals

I know this isn’t going to be a popular thing to say, but film festivals don’t solely look at the quality of a film in deciding which ones should be programmed. They also consider the fit with the festival’s brand, the current political climate, as well as the profile of the film and what showcasing the film, would bring to the festival.

Given that the profile of the film is greatly raised by recognizable name talent, it’s something that festival programmers will consider when deciding whether or not to program your film

Name Talent Increase Your Distribution Options

From my personal experience in distribution and sales, it is easier to sell a mediocre film with names than a great film without them. This is true regardless of genre, although certain genres absolutely necessitate recognizable names if you want any international distribution.

Recognizable Name Talent is a great way to make both sales agents and distributors stand up and take notice. Getting a star in your film has a direct and tangible impact on your chances of getting a profitable distribution deal.

Without recognizable name talent, it’s almost impossible to get a minimum guarantee. Further, many of your international sales will be revenue share only. With Name Talent, it’s far more likely that you’ll get a minimum guarantee from the sales agent, and the deals with international buyers will be license fees or MGs instead of revenue share deals.

Name Talent Increases Self-Distribution Sales

Finally, even if you plan on self-distributing your film, recognizable name talent will help you move units. Raising the profile of your film by having a star in your film will help you place higher in Amazon and iTunes search results, which will have a tangible impact on your bottom line.

Thanks so much for reading. If you enjoy my blog and want more, you should sign up for my FREE independent film business resources package. It’s got an e-book with a lot of articles like this one you can’t find elsewhere, as well as templates to help you grow your film career. One of the articles in the e-book includes a script for calling actors’ agents. Click the button below for more information.

How do we Get More Investors into Independent Film?

How do we get more investors in the film industry? We improve the viability of film as an asset class. Here’s how.

Throughout writing this blog series, I’ve been told more times than I can count that film is a terrible investment, and no one besides hobbyists would consider it. Many want to leave it there, without bothering to look at what’s causing it. Last week we thoroughly examined the issues plaguing the film industry, and what keeps investors out. The issues aren’t pretty, but they may be fixable. What follows is a list of what could be done to fix this problem and some of the ways organizations that are implementing these tactics.

Greater Transparency

One of the biggest things stopping film investment is the perception that it’s unprofitable. All too often that’s not simply a perception. Another thing stopping independent film as an industry from being profitable is the fact that many sales agents don’t accurately report the earnings of the films they represent. Others charge too much in recoupable expenses, so it’s unlikely to recoup. Some take an unreasonable portion of the revenue or simply hide sales from filmmakers.

One necessary problem to fix is the lack of transparency within distribution. There are rights marketplace solutions like Vuulr and RightsTrade emerging thanks to recent technologies for international distribution. Aggregators like BitMax and FilmHub have been around for a while already. The issue that these platforms have yet to solve is that of both audience and industry awareness of their project. If a filmmaker can market or receive help with that audience discover and marketing, then in theory the entire process can be disintermediated and filmmakers can sell directly to customers using a marketplace. Unfortunately, this discovery issue is still both time-consuming and expensive.

What about a hybrid system? One where a skilled group works with distributors and sales agents to sell the completed films at the maximum possible profit to the investors and production company. What if those groups were directly linked to protecting the investor’s interests, and gives sales agents capital for growth and new projects? Then the sales agents would have much better incentives to ensure the companies that license their content to them get a strong return.

That would seem like a solution, but we’ll get to it. There are other problems to delve into first.

Better Business Education for Filmmakers.

I touched on this in my last blog, but filmmakers don’t understand the business well enough to function as media entrepreneurs. Traditionally, specialists such as executive producers, PMDs, and true producers focused on the marketing and supported projects so that the writers, directors, creative producers, and line producers could focus on making the project. With film sets getting leaner, there aren’t enough of media entrepreneurs doing their jobs. (although I take on this role from time to time.)

In essence, there isn’t enough of a skilled entrepreneur class capable of making and selling films as a product either directly to consumers or to distributors, sales agents, and other industry outlets. So long as filmmakers don’t understand business, they’ll never be able to break out and get what they and their films are worth. If filmmakers don’t endeavor to understand business, they will be unable to communicate with investors and understand where they come from well enough to make a sustainable living in film. This issue is exacerbated by the fact that film schools don’t teach any of these skills as well as they should.

Filmmakers want to make the movie, and they will stop at nothing to get that done. As a result, promoting the film becomes an afterthought far too often. What would be ideal is if these educational organizations could tie into an angel investment group or community.

But what about integrating with an investor class and/or investment group?

Educated Investor Class

Investors generally understand business, but the film industry is ripe with its own nuances and idiosyncrasies. Investors need to know how money flows from them to create the product, then to take the product to market through various forms of distribution, and how that money eventually gets back to that same investor. Investors need tools to tell when someone is offering a con instead of an investment. It’s not the easiest thing to find information on, and when they do it’s focused more on the filmmaker than the investor.

If an investor doesn’t understand the issues within the film industry, then it’s less likely they’ll be able to properly vet an investment. If that same school that teaches filmmakers business, could teach investors about the nuances involved in the film industry, then there could be something of a connection point at a different sort of event.

Curators and tastemakers with Access to MEANINGFUL Distribution.

Just because an investor knows about how money comes in and out of the film industry doesn’t mean they can find quality films in which to invest. Being a professional Investor is all about quality deal flow. Indiefilm success tends to make less money than a successful technology startup, so curation and guidance is even more important.

Sure, nobody knows everything, but a curated eye can help separate the wheat from the chaff. Most investors don’t have a trusted source to review projects for feasibility and potential returns. Investment is about more than just money. Investors often act as business advisors. Unfortunately, not enough angel investors understand the industry well enough to do that effectively. However, if the curation board also acted as advisors on the projects, then the potential returns get much higher.

As an example, if that board had access to distribution, then you could cut out the biggest risk of investing in film. A member of the curation board could get the films to the proper PayTV, TVOD, SVOD and other distributors to help the fund managers.

A way of Discovering new talent

It’s always been a problem to find the next Quinten Tarantino, Jennifer Lawrence, or Jason Blum. Everyone has heard stories of how everyone in Hollywood is related. While it's more true than anyone wants to admit, the on set path to grow your career has become more difficult and less sustainable than it once was.

It's not an easy problem to solve. It’s difficult to tell the difference between that person who’s DEFINITELY going to be the next big thing but ends up washing cars two years later and the dweeby 20 year old who no one thinks will ever make anything of themselves makes millions at the box office on their directorial debut. This problem may be the most difficult of any listed.

Making your first film is incredibly difficult. It’s also very difficult to get it financed. From an investor perspective, they put in all the money up front ant they’re the last to be paid. It’s incredibly high risk with little reward.

Marketing a film is also quite difficult, and generally involves additional expenditure when the coffers are dry. This has killed many films before they saw the light of day. If a fund were to offer finishing funds to new filmmakers, they keep their risk incredibly low while opening up new discovery options.

Sure, it doesn’t help get the film made in the first place, but it can help get it finished and out there. The barrier to entry of having a nearly completed film also cuts down on the pool of potential applicants in a way that necessitates them showing they have the mettle to actually make something. That fund could also give preference to successful filmmakers for their second, third, and fourth projects. Such a system could enable a fund to retain the quality people they need to make a successful organization, while still opening the ranks for discovery.

Staged Financing

Investment in film is inherently speculative an as a result incredibly high risk. But the risk could be made lower by borrowing some techniques from Silicon Valley VCs. Instead of funding 100% of a film upfront in equity, an investor could stage their investment over the course of the film, at key points where the filmmakers would require more money.

It’s not something that could be done with a simple line in the sand due to the difficulty in getting recognizable name talent on board the project, but there are systems that could be used to mitigate risk while maintaining the ability to make high-quality name-driven projects that have a higher chance of financial success than directorial debuts with no names attached. It’s not a magic bullet, but it could mitigate the problem enough for other solutions to be more possible.

Staged financing would make it much more approachable for investors, since the risk to the individual investor is significantly smaller. But there are ways an organization could further limit the risk. How you ask?

Same Funder Providing different securities.

As mentioned in part 6 of this series, equity investors are the last to be paid on most projects due to where they fall in the waterfall in relation to Platforms, Distributors, Sales Agents, and the like. This is due in part to filmmakers needing to secure debt-backed securities from different funders in order to complete the project. These debt-backed securities must be paid before the investors are, which further disincentives the equity investment from the original investors.

But what if the different securities were made available from the same group? That way a fund could offer the same pool of investors the last in first out debt in order to protect the interest in their equity position. From my vantage, that would seem to protect both the investor and the filmmaker by enabling the investor to mitigate risk and the filmmaker to maintain greater ownership of their projects, and a higher profit share once the debt is paid off.

Thanks for reading. This one required A LOT of rewriting as part of the archive transfer/website port. If you made it this far, you should sign up for my email list to get my free film business resource pack. You’ll get blogs just like this one segmented by topic, as well as a free e-book, investment deck template, contact tracking templates, form letters, and more!

Check out the tags below for more related content!

6 Things stopping a sustainable investor class in film.

If you’ve ever raised money to make a film, you know it’s hard. It’s not because individual films can’t be good investments, it’s that the problems with the industry are systemic. Here’s a look at why.

Much of this series has been focused on the numbers behind film investment. While metrics like ROI and APR are very important when considering an investment, they’re not the only reason that high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) tend to shy away the film industry. Here are 6 things that are stopping them.

In order for independent film to develop a sustainable investor class, the asset class itself needs to be taken more seriously. The reason that no one has yet been able to create a sustainable asset class out of film and media is much more complicated than the numbers not being in our favor. In this post, we’re going to examine some of the other things stopping independent film from becoming a sustainable asset class. This list is in no particular order, except how it flows best.

1. LACK OF INVESTOR EDUCATION

Investors tend not to invest in things they don’t know or understand, at least as anything more than an ego play. The Economics behind film investment is difficult to understand even before you factor in how difficult it is to find reliable information on film finance from an investor’s perspective.

Even the basics of the industry can be difficult to learn. Generally, film investors are forced to read older, often out-of-date books on film financing targeted more at filmmakers than at investors. This industry is in the midst of a reformation, so much of the information is out of date before it’s published. Most investors don’t really spend a long time learning information from a different perspective which may or may not be correct.

Whit that in mind, many Investors learn how money flows in the Film industry from the filmmakers they invest in. Apart from the conflicts of interest, there’s another rather large problem with that strategy.

2. FILM SCHOOLS DON’T TEACH BUSINESS AS WELL AS THEY NEED TO

Film Schools can be great at teaching you how to make a film, but they’re generally not good at teaching necessary business skills. Even things as basic as general marketing principles, how best to finance a film, or how to make money with a film under current market conditions.

While film and media are an artistic industry, focusing solely on the quality of the film is not going to recoup the investor’s money. Film Schools aren’t great at teaching branding filmmakers how to define their core demographic, or how to access them once they have.

3. DISTRIBUTION ISN'T WHAT IT USED TO BE.

The big risk in film distribution used to be the gatekeepers. You had to make a good enough film to attract a distributor so you could get your film out there. However, that problem has been traded for an entirely different one, oversaturation of content. I would argue that a new problem is harder to overcome.

The old model was that the home video sales would be able to make a genre film profitable, even if it wasn’t that good. Essentially, if you had access to a wide-scale VHS or DVD replicator, you could make a mint selling the licenses. There wasn’t much competition, so a cottage industry sprung up around film markets.

That model worked when it was much more expensive to make a film. Given the high barrier to entry from needing to raise enough money to shoot on film, as well as develop the skills to expose it correctly, there was relatively little competition compared to the demand. However, now that anyone can make a film with an iPhone and 500 bucks the marketplace has been flooded.

Additionally, since the DVD Market has all but dried up, it’s difficult to make a return for newer filmmakers. VOD (Video On Demand) Numbers haven’t risen to the occasion, since most people can get their fix from watching Netflix. It used to be easy to sell DVDs as an impulse buy at the checkout line. Now that everyone has hundreds of free movies at their fingertips, Why should they pay 3 bucks to watch something when there’s an adequate alternative I can get for free?

So the problem is now less how to get distribution, and more how to market the film once you’ve got it. It’s both hard and expensive to market a film. Generally, it’s best to create something of a hybrid between these two types of Distribution. However, there are issues with that as well, and these are less associated with expertise.

4. SEVERE LACK OF TRANSPARENCY IN INDEPENDENT FILM

I’ve written before about the lack of transparency in Distribution, so I won’t go into too much detail here. In Essence, the black box that is the world of film distribution is very intimidating to many investors. Investors want to be able to know when their money is coming back, and many filmmakers are unable to make any real promises about that. However, there’s another issue with transparency from an investor’s perspective.

Unfortunately, many filmmakers don’t communicate well with their investors or other stakeholders. I’ve spoken with many film commissioners, investors, and others about their frustrations with filmmakers not keeping them in the loop.

Filmmakers understandably focus on the admittedly difficult task of making the film happen. Between all of the tasks like scheduling and budgeting the film, finding the locations, confirming the crew, making the shotlist and storyboards, sending out call sheets, and a whole lot more, it’s easy to let communication fall by the wayside.

5. INVESTORS LAST TO BE PAID

Now I know that Filmmakers are reading this thinking “BUT I GET PAID AFTER THEY GET 120% BACK!?!?” To a level, you’re right. However, unless you waived your producer’s fees, you got paid before they did. Sure, you did a lot of work for often too little money to make your film happen, but you did get a fee to produce this film. If your investor wanted to be cynical about it, you produced or directed a movie for hire that you got to take most of the credit for.

Here’s what a waterfall for a film normally looks like. Investors generally did a lot of work to get their money, and now they’ve paid you to make a film and it’s unlikely they’ll ever get all of their money back.

1.Buyer Fees

2.Sales Agent Commission

3.Sales Agent Expenses

4.SAG/Union Residuals

5.Producers Rep (If Applicable.)

6.Production Company

7.Gap Debt (+Interest)

8.Backed Debt (+Interest)

9.Equity Investor

I may be persuaded to do a financial analysis of what that would actually look like in terms of money. Oh look, I did a blog explaining exactly what this means. Click here to read it.

6.LACK OF ACCESS TO TASTEMAKERS AND CURATION

We explored the numbers of why indexed film slates just don’t work in part two. However it takes a fair amount of training, experience, and a bit of luck to recognize what films will hit and what films won’t. While William Goldman is famous for saying “nobody knows anything,” there has to be a balance between a dart board with script titles and industry experts guiding the ship.

Developing an eye for what makes a successful film is something that most prospective film investors don’t want to take the time to learn, especially since many get burned on their first investment. it takes a lot of time to understand what projects have what fit in the market, and that’s generally not something that an investor has time for.

Having a few sets of experienced eyes looking over what investments would be good to fund is something that could make independent film a more sustainable asset class, and not enough investors have access to it to avoid getting burned.

So, what is there to be done about it? Check the next post for the final installment, How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

Also, if you like this content you can get a lot more of it through my mailing list. You’ll also get a FREE film business resource package that includes an investment deck template, contact tracking templates, money-saving resources, a free e-book, and a whole lot more. Again, totally free. Get it below.

Click the tags below for more articles on similar topics.

Which Investment Was More Profitable, Twitter or Paranormal Activity?

When films break out, do they make more money than tech companies? Here’s an examination of 2010s twitter and a fictional investment into the original paranormal activity.

Note from the Web Port: Not all blogs are evergreen. This has nothing to do with Elon Musk, or the state of the platform in 2023. This is an older blog I wrote to illustrate tech breakouts vs. film breakouts. The principle remains, but it’s aged a bit like fine milk. I’m leaving it up as a solid illustration though, since this is basically a 7 part thought experiment. If I were to do it again, I’d compare Skinamarink and Outbrain, Bumble, or DuoLingo. If I get some comments requesting it, I will. Probabably as a video.

BEGIN BLOG PORT

Every tech investor is looking for the next Snapchat, Twitter, or Facebook, and every filmmaker thinks their project will be the next The Blair Witch Project, Paranormal Activity, or Insidious. While there are lots of reasons this ideology is similar, they are far from the same. This week, we’re going to take a look at what an early stage investor in each of these projects or companies would have walked away with.

Films have breakouts, tech has Decacorns. While an interesting word, a Decacorn is easy to describe. It’s a company worth 10 billion or more pre-exit.

Defining a breakout film is somewhat more difficult. There are many ways one could describe a breakout film. In an article for the American Film Market Industry analyst Stephen Follows and Bruce Nash of The-Numbers.com defined it as a film budgeted between 500k and 3 million dollars that the returns to the producer were more than 10 million dollars.

Another way to look at it would be any film that returned their investors at least 10 times what they put in (10X) Perhaps with a minimum return around half a million dollars to avoid a 500 dollar film making 5,000 dollars being considered a breakout. Technically, the two examples of highest ROI films most people think of fall outside this realm.

We’ll be looking at the films people generally think of as winning investments, against the tech companies investors would love to have put some money in early on.

I’m sure every tech investor reading this is thinking a film investment doesn’t really stand a chance. In most instances, they’re right. However, purely as a thought exercise, let’s look at the numbers.

The seed round for Facebook was 500,000 Dollars, and if you’re an aspiring Venture Capitalist or a big fan of Darren Aronofsky, you know that largely came from Peter Thiel of Founders Fund. By the time he cashed out, his initial 500k investment netted him around 1 billion dollars. That’s a return on investment of more than 2,000X! Not all of the money went to him, but a significant portion did. That’s according to this CNN article.

I couldn’t find another similar investment profile for Twitter. Perhaps because no one made a movie about it. So we’re going to have to extrapolate a bit, and estimate what a Series A Investor would have gotten from their investment using largely standard practices and math.

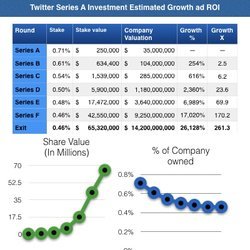

Crunchbase doesn’t have an exact amount that any individual invested, but since it was into a Series A round of 5 million dollars with 11 other investors several of them funds it’s reasonable that a single angel investor could have invested around 250k. Given that 250k investment was against a valuation of 35 million, that means this investor had owned 0.71% of Twitter.

Now, just because this nameless investor owned 0.71% of Twitter then, that doesn’t mean it stays at that percentage. Any time new stock is issued, that share dilutes. Given the valuations of future rounds, we can assume that the 0.71% of the company diluted to around 0.45% of the company by the time the company exited. Given that the company was evaluated at 14.2 billion dollars when Twitter IPO’s in 2013, the initial investment of 250k was worth 65.3MM. That means a 261X return

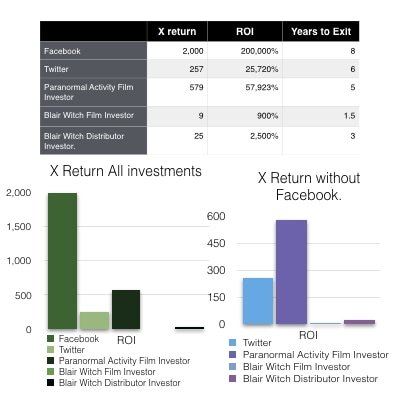

A 250X to 2,000X is a phenomenal possibility, and they're not the only tech companies to have offered such gigantic returns to their early investors. So how does film stack up?

Let’s look at the Blair Witch Project. According to this article from movienomics, the Blair Witch Project Sold at Sundance for 1 million USD. Since the Budget was only 22.5k, the filmmakers made a return of 4340%, or 43X. From the filmmaker side that’s not bad, but it’s not where the story is. Artisan, the company that bought the rights to the film, spent another 1 million US in a grassroots marketing campaign, and the film went on to gross 248 Million. That means they had around a 123X return on their 2 million dollar investment.

We’re going to look at this two ways. From being an investor in the film and an investor in Artisan. If you happen to be that rich uncle who ponied up the 22.5k, you probably would be entitled to around a 20% stake given that almost all of the crew on the Blair Witch worked for free. So, you investment would return about around 200k, or nearly 9X.

What if you were an investor in Artisan? On an entirely hypothetical and not entirely connected to reality basis, let’s just say you were an angel investor who got their money from inventing a new washing machine. You sold the invention to a big company and now you’re flush with cash. You’ve always liked movies so you invest 2 million in Artisan. In return, they give you 20% of their company. So, with that 2 million dollar investment, you get a return of about 25x. That’s a very healthy number.

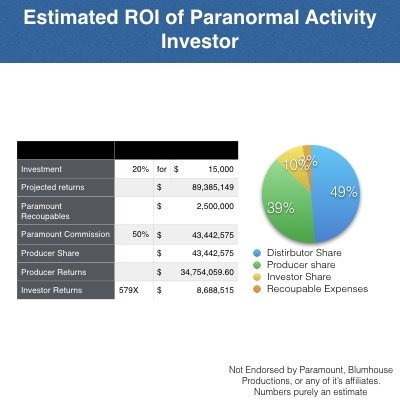

Paranormal Activity is such a low budget, the filmmakers almost certainly put it in themselves, however for the purposes of this exercise, we’re going to assume the entire 15k budget was put in by a single investor, and they took a 20% stake since the filmmakers clearly raised much more in soft costs including deferred payments and sweat equity.

Even though the first film in the paranormal activity series made about 89 million in theaters, not all of that went to the filmmakers. The theaters often keep around 50%, then the exhibitor takes another 30-50% of what’s left, and then the filmmakers and investors get a cut. Further, the distributors tend to recoup their costs first.

To simplify this, we’re assuming that around 50% of the costs go straight to the distributor, and that they recouped another 2.5 million on in expenses before they paid the filmmakers. That’s a low marketing spend, but the campaign Paramount did was very innovative and low cost.

So, if we assume everything above, 89 million gets reduced to a bit shy of 43.5 million once it reaches the Production Company. The investor is then paid out 8.7 million on their initial 15,000 dollar investment, which means a 579X ROI, roughly twice the ROI from the series A of Twitter!

So films are a better investment than Twitter, right? No. No they are not. Paranormal Activity is the highest ROI film of all time, Twitter isn’t the highest ROI tech company within 10 years on either side of it. Further, the returns I listed from Twitter are relatively well verified, I had to extrapolate the deal points for Paranormal activity based on different deal memos I’ve seen as a producer’s rep.

More than likely, the filmmakers put in the 15,000 dollar budget themselves. Even if they didn’t, given that paramount paid around 350,000 up front for Paranormal Activity, the the filmmakers wouldn’t have seen much more from it than that. After all, on paper Star Wars Return of the Jedi never broke even. If the filmmakers only got 350,000, then the investors ROI would have been more like 4.5X given that in our scenario, only owned 20% of the film.

Further, in the real world, both of these projects were largely backed by people who owned the project, and there would have been far more players in the waterfalls. So this is a fun throught experiment more than anything, and mainly proves the point that filmmakers should be focusing on other issues aside from potential ROI when selling their film.

Thanks for reading. This blog was a lot of work to port. If you’re browsing these archives and found it, you probably appreciate my work. If so, I’d ask you to sign up for my mailing list, support me on Patreon, or subscribe on substack. Thanks so much!

Can a Film Slate Make More than a Tech Portfolio?

Most people know film is a bad investment. There is one potential saving grace though.

Edit from the future: Maybe, but probably not, and don’t count on it.

In a quote often attributed to Albert Einstein, “The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.” He also called it “The 8th wonder of the world, he who understands it, earns it. He who doesn’t pays it.” In this post, we’re going to be examining how we can use the notion of compound interest in comparison to tech and film investments.

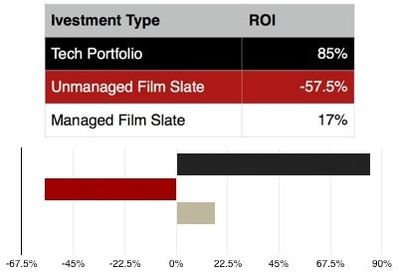

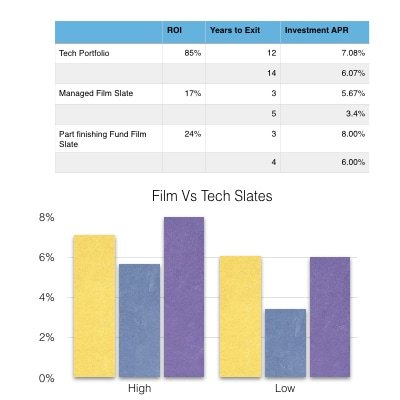

In the previous installment, we looked at the average ROI of a film slate vs. an early stage tech portfolio. Here’s what we came up with before. For the full tables and Metrology, check out last week’s post.

Unfortunately, the numbers don’t look good for film. By the math above, we can see that tech portfolios make on average of 7.5X what a film slate would over their lifespans.

But, film does have one advantage over tech. The amount of time that it takes for a film to recoup [if it’s going to] is much shorter than what it would take for a tech exit would be.

For instance, the average time from when an Angel becomes involved in a project to when they see their money back is around 12 years. For a film to at least start recouping investment, that time period is around 2-3 years, if it’s done well and distribution is planned from the beginning.

Why is that? Generally, for a tech investor to get their money back, the company they invested in has to either be acquired by a larger company or make an initial public offering [IPO] and be listed on a stock exchange. Sometimes an investor will be able to list their stock on a secondary exchange, but that’s a little beyond the scope of this article. Acquisitions tend to happen more quickly than IPOs, but there’s generally less money and less prestige.

Given that the size of venture capital [as opposed to angel investment] rounds have ballooned in the last decade, many venture capital firms are pushing their companies to IPO instead of be acquired. This may make the time from an early round angel investment to exit take even longer than the 12 years mentioned above.

Films, on the other hand, start getting some of their money back shortly after they start distributing the film. If the filmmakers get a minimum guarantee [MG] they may get a decent check up front. If they don’t, they may not, and it may take an additional year or so to start getting their money back. I should note MGs are more the exception than the rule.

So for this exercise, we’re going to look at the APR of both a technology investment portfolio and a film slate. We’re going to make the assumption that both investments are early stage, since the angel round for a technology company is very early in the investment process, generally directly after the friends and family round. Later rounds are generally dominated by institutional investment firms. A similar scenario can be said about film. Most angels from other industries get involved very early, since they don’t have contacts with completed projects.

Since revenue from a film tends to come in over time, we’ll count the lifespan of a film investment to be 3-5 years as opposed to the 2-3 years mentioned above. 3-5 years should be enough time for 60-80% of a films total revenue to come in on average. As such, since this series is largely a thought experiment we’re going to think the general earnings of a film to come in overt that shortened timeframe. Tech exits on the other hand generally come with a large lump sum for the investor after a quite a long time that may be getting longer, we’re going to do the math based on 12-14 years to exit for a tech company. Some do come in much faster, but some films also get bought out for millions after 18 months. They’re outliers and not generally worth accounting for when planning to pitch an investor.

Tech portfolio APR

When we compare APRs, this is starting to look a little more reasonable, but still not great. When we compare the APR of a film as opposed to a technology company, we’re only looking at around a 1.5X to 3X instead of a 7.5X differential. Unfortunately, looking at things through this lens raises other issues, in that the average mutual fund pays out around 5-7% APR, depending on the health of the entire economy.

Could a savvy investor do any better? Perhaps.

Everything we’ve been looking at so far has assumed that all of these investments were early stage. If it were a tech investment, we’d say Seed or Series A, in film, we’ve been assuming these investments take us out of development and into preproduction. But what if we were to include completion funding and distribution funding in the portfolio? I would do a similar analysis for technology companies, however, given that the VCs and hedge funds dominate that world due to the amount of capital needed. In days and years past, these stages would be overwhelmingly covered by distributors, but that’s nowhere near as true as it used to be. This leaves a hole for an investor to come in and increase their potential returns while lowering their risk exposure.

The assumptions I’ve made on the chart above are that the slate would be made up of half of finishing/distribution funds, and half of the early-stage investments. As such, the risks are far lower, and since much of the later stage debt may be done in the form of debt as opposed to equity, we can assume not a huge amount of loss on those investments. Also, since the film needs to be finished and not made from the start, the time for the recoupment of these funds is greatly lessened. With that in mind, we'll assume that the bulk of these returns come in from 3-4 years instead of 3-5.

I'd like to take this opportunity to remind you that none of this is meant to be scientifically accurate, but rather a very good estimate and approximation of what these slates could look like given the right set of circumstances. Take these numbers with a grain of salt, just as you should any revenue projections from a pre-seed stage startup or revenue projections from a filmmaker. This also should not be considered financial advice, nor a solicitation for sort of funding.

Admittedly, these numbers are highly speculative, [See disclaimer on part 1] but the right team backing up the right filmmakers may make it possible. Given I work with investors, I should state these do not constitute any legal documentation, it’s really just a theoretical exercise to help compare two asset classes. Again, not a solicitation.

By creating a slate investment that includes completion funding as part of the investment mix, we lessen the risk and decrease the time to getting the money back. How does that affect the APR?

With the inclusion of completion funding in a portfolio, the APR of a film slate is looking relatively competitive. If you’re an investor, you may be asking yourself, “Well if it makes that big a difference why not focus only on completion funding?” It’s a great question, there are many funds that do. So many in fact, that the playing field is getting fairly crowded. Especially when you compare it to the other funds that focus on development throughout the film industry.

If a fund only offers completion funding, It would be difficult to establish the long-term relationships with the emerging talent necessary to make an organization like this work. It would also be harder to attract high-end prospects for bigger films with more recognizable names. If a fund does a mixture of the two, it can be a very good way to find new filmmakers and help them pass the goalpost on their first film. Once they’ve done that, you can start to work with them on future projects at an earlier stage. By doing this, the fund creates a better vetting process and attracts higher-end talent.

With that in mind, a mix of investments seems to further the goals of the organization and the industry in a much more cohesive manner. It also starts to sound a lot like Staged Investments, like Seed Stage, Series A, B, C, and the like. Don’t worry, we’ll have a much more in-depth conversation about this later in the series, as well as a couple of other blogs on the site tagged “Staged Financing”

But first, We’re going to talk about some of the excitement associated with both of these types of investment. The Decacorns and Breakouts. That blog can be found below. Again, for legal reasons I need to state that none of this should be considered financial or legal advice, as I am not a lawyer nor a financial advisor. Further, this is not a solicitation for funding or investment.

The only thing I will solicit you to do before finishing up this beast is a blog is to join my mailing list so you can grab my free film business resource package. (segues, eh?) It includes a FREE Deck template to help you talk to the investors you’re probably considering approaching if you’re reading this. It’s also got a free e-book, and other money and time-saving resources. Check it out below.

Why Angels Invest and Why they Choose Tech

Most Filmmakers need Investors to make their movies. To convince an investor to back in your indiefilm, you need to understand why they invest in anything,

Why should those Rich Tech [People] Invest in your Film, Part 2/7

In order to understand why an investor should invest in your film, you need to understand why investors invest at all. What is an angel investor? What does it take to be a successful angel investor? Why don’t they just buy that Second Third yacht?

To answer the first question, an angel investor is person of means, who generally has a sizable amount of liquid assets and wants to do something more interesting and potentially lucrative than buying stocks or mutual funds. In order to be an accredited investor, an unmarried person must have made at least 200,000 USD for two consecutive years, and be likely to do the same in the current year. If they’re married, that number is more like 300,000 USD. They could also have 1,000,000 in liquid assets, not including their primary residence.

The reason this came about was to protect individuals from being taken by scam artists. The theory behind the income threshold is that if you’re that affluent, you would either have the education or sense to know if you’re being taken, or the means to hire someone who does.

Apart from the aforementioned asset requirement, what does it take to be a professional angel investor? It basically requires two things. Access to capital and deal flow. In layman’s terms, money to invest and projects to invest in. Most of the time, Investors generally assume that about half of their investments will tank and they’ll lose everything due to an inability of the company to exit.

So why do Angel Investors invest? This question is more difficult to answer and actually has several answers that we’ll explore throughout this blog series. But, essentially it boils down to the fact that These investments have the potential to breakout in a big way.

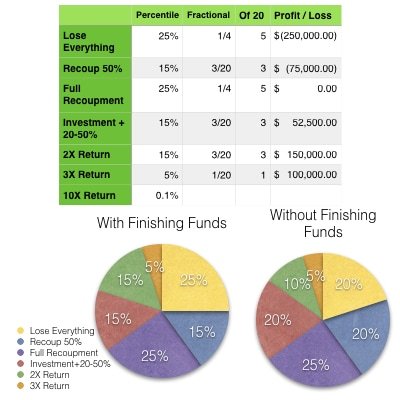

Below is a chart illustrating that point. It has been simplified and assumes very early-stage investments. This chart is generally based on loose feelings and assumptions asserted by many investors I’ve talked to. Just like it’s very difficult to estimate how many films break out, it’s very difficult to estimate how many investments are completely lost. It’s very easy to track winning bets, but much harder to track losing ones. This data is accurate to the dozens of investors I know as to their top-level assumption and the data around films is accurate to my experience as a distributor.

Before we get into any numbers, I should preface I’m not a financial advisor, this is not financial advice, nor am I soliciting for any particular project. This is all conjecture and an extrapolation and explanation of personal experience.

If you’re a filmmaker reading this, you might be thinking to yourself, why are they hunting mythical horses and WTF is a decacorn? A Unicorn is a company valued at more than 1 billion before exiting. If you’re a decacorn, your company is valued at more that 10 billion prior to exit. The reason that you don’t really see it on that pie chart is that it’s only about 1 in 1000 to 1 in 10,000 chance of happening.

So how do investors get their money back from a tech investment? in order for a tech investor to get their money back, generally the company has to be acquired, or go public [IPO.] Films on the other hand, simply need to find profitable distribution, or self-distribute the product. Each exit in each sector have its pros and cons, but in the end the boils down to which is more accessible. So what does the return look like in both cases?

Let's assume an investor invested One Million Dollars across 20 tech sector investments, each investment is made equally. I know that these tables are going to be hard to fully understand, so I’ll have a better data visualizations after table 3.

As you can see the overall ROI is about 85%, which means they nearly doubled their money on the entire portfolio. This is assuming that the investor isn’t completely green and has some idea of what they’re doing, so they make better picks. At some level, this looks very similar to the studio tentpole system. Experts making bets are confident that the ones that hit will cover the losses of the ones that miss. Unfortunately, the numbers don't back that up in the way we would like, partly due to the fact that most angels in the film stlate are not experts, and many filmmakers don't package as well as they should to maximize potential returns.

What does the picture look like for the investor going with no real knowledge of film look like? Well, from my more than a decade marketing and distributing features, here’s about how that would break out.

That’s not Pretty, but it is making a fair amount of negative assumptions about the slate of films. These numbers are assuming they don’t have distribution going in, don’t know what sells, and the film is financed entirely by private equity. The hypothetical investor made the investment at the outset of the project assuming the entirety of the risk. AND the film isn’t well cast with an eye for international sales.

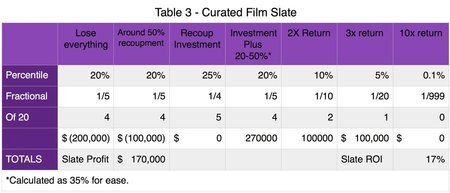

BUT, if you structure your slate look to get at least a letter of intent for distribution a North American distributor and work with an international sales company to ensure the best casting for international saleability. It’s at least possible that you could have a slate that looks more like this.

That’s better, but a well-managed tech portfolio still obliterates it if we go solely by total return potential. The Graph I mentioned is below, to help illustrate my point. Trying to convince a tech investor to break from what they know to invest in something that has less potential to return is a hard sell.

Edit From the Website Transfer: If I were to re-do this, I would probably put the 10x return at more like 0.5-1% as opposed to 0.1%, assuming we account for one in 10 portfolios of 20 films gets a breakout hit, the potential average returns end up around 20-22% depending on which of the pool the breakout comes from. if 2 out of 10 of the portfolios happen to have a breakout it’s closer to an average return of 24-26%

Filmmakers, this is what you’re up against. But fear not, you may have an ace in the hole. In fact you may have more than one. The first ace in the whole is the speed of exit for film projects compared to that of tech startups. Due to that, film projects can return money to the investor faster than a startup would, which matters significantly in increasing the ability for an investor to re-invest and increasing the overall Annual Percentage Rate (or APR) of the investment. Check out part 3 linked below for more information on that.

Part 1:

Why Don’t those “Rich Tech [People]” invest in Your Film?

Part 2: (This Part)

Why Angels Invest, and Why they Choose Tech.

Part 3:

Examining APR: How does Film Stack up to Tech Portfolios?

Part 4:

Breakouts vs Decacorns

Part 5:

Diversification and Soft Incentives.

Part 6:

What’s really stopping Tech Investors from investing in Film?

Part 7:

How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

Thanks for Reading! The numbers in this blog have evolved since I wrote it, but only slightly. If you want to stay up to date on resources, livestreams, and other awesome content I have to offer, you should join my mailing list! You’ll stay up to date on all of my latest content, plus get a free e-book, monthly blog digests, and even a great resource package to help you talk to investors about your film. It’s totally free, so what are you waiting for?

Understanding Money

If you want to make movies, you need money. If you want to raise money, you mist first understand it.

Since my background is at the Institute for International Film Finance, and I put in a year at Global Film Ventures, I get a lot of filmmakers contacting me asking me to help them fund their films. Some of them are good pitches, but most are not. Getting investment for your film is incredibly difficult, if not nearly impossible. There are many reasons for this, but one that is not often talked about is the fact that many filmmakers have a mindset that money shouldn’t come with strings, and that all they should need to worry about is making the film.

There’s this attitude filmmakers have that someone should just give them a check and then go away so they can make the film. I’ve had many filmmakers say that flat out to me, and the ignorance of it is incredibly disturbing. There’s a lot more to investment than just writing checks.

Angel investors didn’t get their money by giving it to just anybody. Investors generally do quite a lot of legwork to research those with who they invest in, and they’ll never invest in someone they don’t trust. This attitude of “just give me the money and let me be” is a huge red flag, and makes an investor far less likely to trust you. If they don’t trust you, they won’t invest in you.

Once you take money from someone, you have a responsibility to them to send periodic updates and let them know how everything is progressing. You need to be available to take their calls at most any reasonable time and always return their correspondence within at most two business days. All money has strings, and you can’t expect an investor to just write you a check and then never check in on you.

Another attitude problem a lot of filmmakers have is that they feel they don’t need to understand business. Many feel just need to make the best film possible and money will come to them. While there’s a kernel of truth in that, relying solely on making the best film possible is a great way to end up broke with a film that never goes anywhere. The best product without a marketing team will never make money. Filmmakers

do need to make a great film, but they also need to understand at least the basics of how to promote a movie and how it will see revenue.

Distributing a film, promoting a film, and selling a film are all incredibly different skill sets that require decades to master. Filmmakers can’t be expected to be experts in every job involved in making a movie. They do, however, need to understand what they don’t know and compensate for that by getting people on their team that do understand how to do those jobs.

In essence, this is the difference between a producer and a production manager, or the difference between an executive producer and a line producer. Line producers and production managers are great at understanding how to manage a crew and get a film in the can. Producers need to have a good understanding of business, negotiation, deal-making, finance, and distribution. Executives do the latter almost to the exclusion of everything else. Every film needs at least one of each of these people, and really they shouldn’t be the same person filling multiple roles.

Every film needs people who understand money, how to raise it, how to make it back, and creative ways to save it. Filmmakers of all kinds can be excellent at the last part of that. Innovative bootstrapping is a skill perfected by many guerilla filmmakers. That said, you still need money, and people who understand how to make a film see revenue on your team.

Even if you find an intermediary who can help you get the money from angels, you’re still going to have to have regular phone calls and meetings with that intermediary. In fact, that intermediary is probably going to have more contact with you than an investor would because they understand both investment and filmmaking. You need people like this on your team, and you need to understand that you’re creating more than just a film. Every film is in essence a business, and in order to run a successful business you need skilled business people just as much as skilled artists and visionary directors.

Whenever you seek investment, it is into your business. You need to understand that the business side of the indusry is necessary. You also need to have an appreciation and at least a basic understanding of what it takes to make money in business. This should not be your sole consideration, but it does need to be part of your plan when creating a film. If you do not include this in your plan, you’ll never actually see revenue from your projects.

So readers, if you’ve ever thought that all you need is someone to write you a check; remove that notion from your head. In order to get money, you need to understand money. Only if you understand how money works, and have a good business plan will you be able to successfully get investment and make a profitable film.

The Importance of Specialization to Film Communities.

We all know that there are a lot of problems with most film schools. The foremost being that while they’re great at teaching you how to make a movie, they suck at teaching you how to make money doing it. There’s another one that isn’t generally talked about.

We all know that there are a lot of problems with most film schools. The foremost being that while they’re great at teaching you how to make a movie, they suck at teaching you how to make money doing it. While I’m personally working to fix that one, there’s another one that isn’t generally talked about.

Most film schools take a rather blanket approach to filmmaking. They teach everyone the skills of all positions on set, instead of focusing on being really good at one part of it. Because of this, many film schools are failing to prepare students for the real world they will compete in.

The attitude of being a jack of all trades often leads to being decent at everything, but excellent at nothing. Which is alright for someone who wants to make their own ultra low budget movies or make a few not great corporate clients. Unfortunately, we live and work in a highly specialized and extremely competitive industry. In order to find success, you must to be excellent at your craft. Unfortunately, Few Film Schools operate this way. Most teach you to be a jack of all trades, and it's just not possible for anyone to master all the skills necessary to do every job on set.

Not all of this is the fault of the schools. Most of them do offer specialization into Cinematography, Directing, Producing, Editing, Writing, and often even acting. However even with this specialization, many filmmakers are forced to perform most of the jobs on set, and get an attitude that they must do it all. Filmmaking is an incredibly collaborative medium, and it is an incredibly collaborative medium, and an attitude of one person being able to fill any and all jobs on set is counter-productive for the creation of high quality projects.

This is not the case for all film schools. The ones considered to be the best still prepare you to be excellent at one job. USC and UCLA foremost among them. However the same cannot be said for most film schools

Directing is always a difficult specialty. Nearly everyone wants to be a director. However if you want to be a director, then the best thing you can do is learn to direct actors. Directors need to have a vision, and they need to understand every part of the film, but the best directors are the ones who truly understand how to work with actors.

A director is responsible for nearly every creative element of the film, but much of it is delegated. Cinematographers handle the camera, Gaffers the lights, and editors the cuts. Performance is the only element left entirely to the director. It's important it be the director's primary focus, for better or worse, The performances will carry much of the project.

Cinematography is a skill that’s extremely transferrable, if you do it well. And a good cinematographer can always find work. But it is also good for a Cinematographer to know not just how to Light, but why to light. How can you paint a picture with shadow, and how can your dynamic range effect the feel of the shot. As a cinematographer, you must understand how to use every tool in your toolbelt.

A backing in photography is excellent for this, and can lead to a lot of work while you build your career and client base. Having your own gear and an understanding of how to create a stylized look can help you land a very good job with an ad agency or find your own clients while you network to get on projects you're more excited to be working on.

However, there's a lot of exciting things going on in the world of content marketing.

Writing is tough, the competition is high and everyone thinks they can do it. I've had bartenders and Lyft Drivers ask me to represent their scripts while in LA on business. As we all know, while anyone can write, few do it well. Even if you can write well, it is often difficult to break in. The most useful specialization for a screenwriter is learning to give coverage. It's hugely important and incredibly useful, and it also helps you develop relationships with producers. Another thing that writers, and everyone if I'm honest, is to write good copy. Spending a few hours learning the basics of copywriting will help you go so much farther in the world of independent film.

This whole Idea of specialization will help you to fit better into a larger film community. If you have something you can bring to the table for your community, it’s a lot more likely you’ll be able to find success. If we’re to really grow vibrant film communities outside of New York and LA, then the idea of specialization really needs to reach the local level that can compete with the production quality of the major hubs. That’s not possible without specialization.

There’s not much more specialized than being an executive producer. We focus solely on the business of entertainment and our skillsets are not always easy to find. If you’d like to know more, you should check out my free film business resource package for time and money-saving resources, templates, and even a free e-book! Join below.

If you want to stay specialized where you are, you might want to consider hiring a producer’s rep so you can focus on what you do best. If so, check out our services page. If you just like the content, and want to see more, check out my patreon and substack.

Why Film Needs Venture Capital

Part of creating a sustainable revolution in the film industry is creating a new system of finance. For that, we should look to other industries starting with Private Equity and Venture Capital. Here’s how we do that.

A lightbulb next to a chart outlining the allocation of venture funds in 2011 above a text blurb outlining the data source.

There’s an old joke that goes something like this. Three artists move to Los Angeles, a Fine Artist, a poet, and a Filmmaker. The first day they’re in town, they check out the Mann’s Chinese Theater. When they get there, a wave of inspiration overtakes them. The fine artist says, “This is incredible, I have to draw something! Does anyone have a piece of chalk?” Low and behold a random passerby happens to have one, and hands it over. The fine artist does a beautiful rendering on the sidewalk.

Watching this, the poet says, “I’ve had a flash of inspiration, I must write! Does anyone have a pen and paper?” It happens to be a friendly sort of Los Angeles day, and someone hands over a pen and paper. He writes a beautiful Shakespearean sonnet about his friend’s artistry with the chalk.

The filmmaker says “This is amazing, I’ve got to make a movie about it! Does anyone have any money?”

Even though the costs of making a film have been cut drastically, the joke remains true. I mentioned in my last post that the film world is in need of new money, and that what the film world really needs is something akin to Venture Capital. I think the topic deserves more exploration than a couple paragraphs in a post about transparency.

Venture capitalists bring far more than money to the table. They also bring connections and a vast knowledge of financial and industry specific business knowledge to the table. Essentially these people are experts at building companies, and when you really break it down the best films really are just companies creating a product.

The contribution of connections and knowledge is just as vital to the success of the startup as the money is. We have something somewhat similar in the film world, it’s generally the job of the executive producer to find the money for the film and put the right people in place to run the production and complete the product.

The biggest problem is that good executive producers with contact to money are few and far between, and there are very few connection points between the big money hubs and the independent film world. Filmmakers often don’t only need money, they need to have an understanding of distribution and finance that many simply do not have, and most film schools just do not teach. These positions are generally not full time positions, and most filmmakers just don’t have the money they need to pay people like this. If a venture capital model were to be adapted in film, the firm could link to these experts, and included in the budget for the film at a cost far less than it would normally be, because the person could split their time between all of the projects represented by the firm.

Most people understand that filmmakers need money, what many people do not understand is that there are very valid reasons for an investor to invest in film.A good investor knows that a diverse portfolio is far better than one that focuses solely on one industry. Industries can change and the revenue brought in by any single industry can crash with little notice. Savvy investors will seek to have money in many pots as it really helps to weather through downturns. Film is considered to be a mature industry, and has grown steadily over the past several years, even in the economic downturn. In fact, the film industry is moderately reversely dependent on the economy, so it often does better in economic downturns.

The biggest problem is that most investors just don’t invest in things they don’t know. Investors need to understand an investment before they put money into it.

Film is a highly specialized and inherently risky business. All the money goes away before any comes back, and that can scare off many investors. Especially since they often don’t understand what a good use of resources for a film is and are often incapable of seeing when the project should be stop-lossed as to not lose any more money.

One solution a venture capital firm could bring to this industry that single investors simply cannot is stage financing. Stage financing is a system of finance that is widely used in Silicon Valley. The concept is basically that the investors only release funds once certain checkpoints are met. Single angel investors do not have the time or expertise to act in this way, which is a big part of the reason for the standard escrow model. If a project that makes it through the screening process is only given the money they need for pre production up front, they must pass a review to have funds released for principle photography then it becomes a far more sustainable investment.

Filmmakers may balk at the idea of review, but quite frankly so long as the production is being well managed, they should be able to complete the checkpoints and have the additional funds released with little difficulty, assuming that the right review panel is put in place. The fund itself has every reason to see it’s projects through to completion, so it will only be filmmakers who are not doing their jobs that end up not passing the review process.

Edit: Additionally, there are deals that can be made to help agents and bankable talent feel more comfortable with such a process. This may be a subject of a later blog, and is mentioned in the comments.

Why does the fund have every reason to see films through to completion? Because if the films are not completed, then the fund will have lost all the money it put in with no chance of getting it back. That said, if the production is a disaster, and it’s clear that additional funds would not actually result in a finished and marketable film, then it is far better to cut losses and move on with other projects that have higher potential for revenue.

As mentioned in the last blog, a lack of transparent accounting is also a big issue with investors.

A single filmmaker does not really have the ability to negotiate with a distributor, at least not to a level necessary to resolve the transparency issue. In the relationship, the distributor has all of the power and there’s really very little most filmmakers, especially those just starting out, can do to change that.

But in film as in any industry, money talks. If there were a venture capital firm for film that only worked with distributors who have transparent books, and those distributors could then turn around and propose new projects to the venture capital firm, then some of the issues of transparent accounting could start to change. Many distributors, especially those working in the low budget sphere, are continually raising money for their own projects. So, having a good relationship with a venture capital firm is a big incentive to maintain good books and responsible business practices for filmmakers.

It got listed in the comments section of Black Box that filmmakers shouldn’t necessarily need to have that much business sense, since it takes their whole being to create. Filmmaking is indeed a collaborative effort, and it’s not a director’s job to think about target demographics and marketing strategies. The problem is the people in the film world that truly understand investment and recoupment are few and far between. Many of them also take advantage of filmmakers, as evidenced by the stories of studio accounting from Black Box. Part of what’s needed is the creation of teams that have what it takes to both tell quality stories with high production values, also get the films to market and figure out exit strategies, target demographics, and general budget recoupment tactics.

Many Film Schools just don’t teach this part of the business. Film schools focus everything on how you can make the film, and what it takes to do it, but few of them really give you the ability to actually go raise money. So what’s really needed is a new class of producer that understands the executive side. What’s really needed is a new class of investor that understands what it takes to invest in film, the risks, the rewards, and how it’s diversified. What’s really needed in film is a company that can successfully link the two together, and create a new class of media entrepreneur. What’s really needed is an incubator for independent film with a team that can execute both of these aspects and create a sustainable business model out of it.

Right now no such organization really exists. Legion M has some elements of it, but they miss the new talent discovery elements in favor of risk abatement. Slated works similar to AngelList, but I’m not sure their track record is what it needs to be to justify their price point. I’ve been trying to start one between my various projects with angel groups, Mutiny Pictures, Producer Foundry, and other ventures. It’s clear that the industry is changing, but quite frankly it needs to. The best way to effect the change in practices that need to happen in the industry is to change the way the industry is financed. The entrance of a film fund that operates on principles more akin to the aspiraations of a venture capital firm would do just that, and is exactly why it needs to happen.

If you enjoyed this blog, please share it to your social media. You should also join my mailing list for some curated monthly blog digests built around categories like financing, investment, distribution, marketing, and more. As well as some templates (including a deck template) as well as other discounts, templates, and other resources.

Check out the content tags below for related content

Black Box - a Call for Transparency in Film

The concept that Film Distributors aren’t telling you the whole truth isn’t unknown. However, the problem is deeper than you may realize. Here’s why.

A Black cube on grass in a yard, with the Title “Black Box” in the upper left corner and the subtitle “An In Depth Analysis of ‘Hollywood accounting” in the lower right corner, and logos for Guerrilla Rep media and PRoducer Foundry in the lower left corner.

Photo Credit thierry ehrmann Via Flickr, Modifications made to add title, subtitle, and logos

The process of Filmmaking has been evolving rapidly over the past decade. With the massive change in the availability of equipment, negating the need for tapes or stock, and bringing the professional quality down to a price point thought unfathomable merely a decade ago, the barrier to entry for making a film has been almost completely obliterated. Additionally, education on how to make a film has become widely available, from the massive emergence of film schools to a plethora of information available in special edition DVDs, anyone can learn how to make a film. However, the same cannot be said for Film Distribution. Film distribution is still a black box from where no light or information emerges. There is a very palpable air of secrecy around film distribution, and now that film production has become available for anyone curious enough to seek it, it’s time the same is done for film distribution.

I’ve always loved movies, and I’ve been making films in some fashion for nearly a decade. Even though that’s really not that long, I realized that when I started, camcorders were still fairly rare among middle-class families, and far rarer among high school students. Even the local Access channel worked with three-chip cameras, and those who could afford it swore by the film. That landscape is now nearly unrecognizable, now every other high school freshman carries a 1080p camera in their back pocket anywhere they go. This process has been going on for decades, far longer than my personal experience.

In the 70s, even Super 8 home movies were few and far between. To make a movie in the 70s involved an incredible amount of time, effort, and skill. Many learned by trial and error, with limited training and education often in the form of watching the great films of their eras. In those days, no one went to Film School, because there really weren’t that many of them. You pretty much had to go to New York or LA.

Even those who entered the industry in the 60s and ’70s often went to school for something else. Today, there are 389 Film Schools spread across 43 states, which considerably changes the landscape for Education.

However the same cannot be said for film distribution. Despite the fact that technology has evolved beyond what even the most visionary filmmakers could scarcely imagine back in the 70s. Much of it is still a black box where even the most simple information about budgets and returns are kept largely under lock and key. Studio accounting and net proceeds are just as secret now as they have been since Jimmy Stewart became the first Actor to be a net profit participant back in the 50s.

Even if you made a film that’s being represented by a distributor, many of them will not share accurate information regarding the returns you’ve made. A simple balance sheet is difficult to track down, and even if you can get one it’s often hindered by studio accounting, and the breakeven point is never reached, so the filmmaker never sees his or her share in the net proceeds, also known as profit participation. If filmmakers don’t make money making films, then all they have is an expensive hobby that is unsustainable in the long term. The problem is so vast that even Star Wars Episode 6 never made a profit. Even if they can get their first project bankrolled, unless they can make a profit on their film it is unlikely that they will get to make another one. In the independent film world, most times if the producer never sees their share in the net proceeds, then neither does the investor who footed the bill.

If the investor doesn’t see profit, then they won’t be an investor for long. Unlike the filmmaker, most of them won’t continue to do this just for the vision. The first thing any savvy investor will tell you is that they only invest in what they know. And while they may now be easily able to find information on the process of making the film, the metrics measuring the performance of independent films are unclear and almost always unreliable. If an investor can’t decode and project revenue through clearly definable analytics, most of them are far less likely to close an investment deal. Even if they do invest, if they feel like the distributor is not telling them the whole story, they generally won’t invest again.

If the Industry is to change, new money to enter it. The old money is tied up in sequel after sequel, and rehashes of old stories. The movie-going public is fed up with it and want something new, different from the old franchises. This leaves a demand in the industry for quality content that is simply not being filled to the extent it needs to be. In a way it’s similar to the ’60s and early ’70s here in San Francisco when Venture Capital was just starting, there are many talented young people with great ideas, but little business sense.

The studios are entrenched in the old ways of thinking, and behemoth companies don’t adapt well to change. Startups do adapt well to change, and they really can change thought processes through ideas that take hold. The Film Industry is changing more rapidly than ever before, it will likely be just as unrecognizable in another 5 years as it was 10 years ago. Anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The old companies and the old money can’t adapt as quickly as things are changing, so logically we need new ideas and new money to enter the industry and shake things up.

This is exactly the effect that Venture Capital had when the Traitorous Eight left Shockley Semiconductor to start Fairchild, and then left to start other companies that eventually became Silicon Valley. Fairchild was only able to be started due to a new idea that evolved into what is now known as Venture Capital. In order to effect change as quickly as is needed, something similar must happen in the film industry. But Venture Capital can’t enter an industry where the risks are incalculable. Without a more transparent method of accounting, the risks are indeed incalculable.

The industry is evolving more rapidly than ever before. The future is unclear. It’s a wide-open frontier where anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The process of film production has moved out from the dark rooms and light-proof magazines of old and exposed for all to see. It is time for the business side to do the same. It is time for every filmmaker and investor to have a clear understanding of Distribution. It is time for daylight to expose the studios’ accounting practices. It is time for transparent accounting in film.

While there's not a lot an individual can do about the lack of transparency in the film industry as a whole, there are ways that we as individuals can band together to have an impact. Those tactics are some of what I tried to implement at Mutiny Pictures, and what I address in my content, groups, and consulting. One of the goals of porting over my website was to greatly lessen advertising and sales, but check the links below to learn more about ways you can impact not only your career but the industry as a whole. More details on each of the buttons found below.