6 Things stopping a sustainable investor class in film.

If you’ve ever raised money to make a film, you know it’s hard. It’s not because individual films can’t be good investments, it’s that the problems with the industry are systemic. Here’s a look at why.

Much of this series has been focused on the numbers behind film investment. While metrics like ROI and APR are very important when considering an investment, they’re not the only reason that high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) tend to shy away the film industry. Here are 6 things that are stopping them.

In order for independent film to develop a sustainable investor class, the asset class itself needs to be taken more seriously. The reason that no one has yet been able to create a sustainable asset class out of film and media is much more complicated than the numbers not being in our favor. In this post, we’re going to examine some of the other things stopping independent film from becoming a sustainable asset class. This list is in no particular order, except how it flows best.

1. LACK OF INVESTOR EDUCATION

Investors tend not to invest in things they don’t know or understand, at least as anything more than an ego play. The Economics behind film investment is difficult to understand even before you factor in how difficult it is to find reliable information on film finance from an investor’s perspective.

Even the basics of the industry can be difficult to learn. Generally, film investors are forced to read older, often out-of-date books on film financing targeted more at filmmakers than at investors. This industry is in the midst of a reformation, so much of the information is out of date before it’s published. Most investors don’t really spend a long time learning information from a different perspective which may or may not be correct.

Whit that in mind, many Investors learn how money flows in the Film industry from the filmmakers they invest in. Apart from the conflicts of interest, there’s another rather large problem with that strategy.

2. FILM SCHOOLS DON’T TEACH BUSINESS AS WELL AS THEY NEED TO

Film Schools can be great at teaching you how to make a film, but they’re generally not good at teaching necessary business skills. Even things as basic as general marketing principles, how best to finance a film, or how to make money with a film under current market conditions.

While film and media are an artistic industry, focusing solely on the quality of the film is not going to recoup the investor’s money. Film Schools aren’t great at teaching branding filmmakers how to define their core demographic, or how to access them once they have.

3. DISTRIBUTION ISN'T WHAT IT USED TO BE.

The big risk in film distribution used to be the gatekeepers. You had to make a good enough film to attract a distributor so you could get your film out there. However, that problem has been traded for an entirely different one, oversaturation of content. I would argue that a new problem is harder to overcome.

The old model was that the home video sales would be able to make a genre film profitable, even if it wasn’t that good. Essentially, if you had access to a wide-scale VHS or DVD replicator, you could make a mint selling the licenses. There wasn’t much competition, so a cottage industry sprung up around film markets.

That model worked when it was much more expensive to make a film. Given the high barrier to entry from needing to raise enough money to shoot on film, as well as develop the skills to expose it correctly, there was relatively little competition compared to the demand. However, now that anyone can make a film with an iPhone and 500 bucks the marketplace has been flooded.

Additionally, since the DVD Market has all but dried up, it’s difficult to make a return for newer filmmakers. VOD (Video On Demand) Numbers haven’t risen to the occasion, since most people can get their fix from watching Netflix. It used to be easy to sell DVDs as an impulse buy at the checkout line. Now that everyone has hundreds of free movies at their fingertips, Why should they pay 3 bucks to watch something when there’s an adequate alternative I can get for free?

So the problem is now less how to get distribution, and more how to market the film once you’ve got it. It’s both hard and expensive to market a film. Generally, it’s best to create something of a hybrid between these two types of Distribution. However, there are issues with that as well, and these are less associated with expertise.

4. SEVERE LACK OF TRANSPARENCY IN INDEPENDENT FILM

I’ve written before about the lack of transparency in Distribution, so I won’t go into too much detail here. In Essence, the black box that is the world of film distribution is very intimidating to many investors. Investors want to be able to know when their money is coming back, and many filmmakers are unable to make any real promises about that. However, there’s another issue with transparency from an investor’s perspective.

Unfortunately, many filmmakers don’t communicate well with their investors or other stakeholders. I’ve spoken with many film commissioners, investors, and others about their frustrations with filmmakers not keeping them in the loop.

Filmmakers understandably focus on the admittedly difficult task of making the film happen. Between all of the tasks like scheduling and budgeting the film, finding the locations, confirming the crew, making the shotlist and storyboards, sending out call sheets, and a whole lot more, it’s easy to let communication fall by the wayside.

5. INVESTORS LAST TO BE PAID

Now I know that Filmmakers are reading this thinking “BUT I GET PAID AFTER THEY GET 120% BACK!?!?” To a level, you’re right. However, unless you waived your producer’s fees, you got paid before they did. Sure, you did a lot of work for often too little money to make your film happen, but you did get a fee to produce this film. If your investor wanted to be cynical about it, you produced or directed a movie for hire that you got to take most of the credit for.

Here’s what a waterfall for a film normally looks like. Investors generally did a lot of work to get their money, and now they’ve paid you to make a film and it’s unlikely they’ll ever get all of their money back.

1.Buyer Fees

2.Sales Agent Commission

3.Sales Agent Expenses

4.SAG/Union Residuals

5.Producers Rep (If Applicable.)

6.Production Company

7.Gap Debt (+Interest)

8.Backed Debt (+Interest)

9.Equity Investor

I may be persuaded to do a financial analysis of what that would actually look like in terms of money. Oh look, I did a blog explaining exactly what this means. Click here to read it.

6.LACK OF ACCESS TO TASTEMAKERS AND CURATION

We explored the numbers of why indexed film slates just don’t work in part two. However it takes a fair amount of training, experience, and a bit of luck to recognize what films will hit and what films won’t. While William Goldman is famous for saying “nobody knows anything,” there has to be a balance between a dart board with script titles and industry experts guiding the ship.

Developing an eye for what makes a successful film is something that most prospective film investors don’t want to take the time to learn, especially since many get burned on their first investment. it takes a lot of time to understand what projects have what fit in the market, and that’s generally not something that an investor has time for.

Having a few sets of experienced eyes looking over what investments would be good to fund is something that could make independent film a more sustainable asset class, and not enough investors have access to it to avoid getting burned.

So, what is there to be done about it? Check the next post for the final installment, How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

Also, if you like this content you can get a lot more of it through my mailing list. You’ll also get a FREE film business resource package that includes an investment deck template, contact tracking templates, money-saving resources, a free e-book, and a whole lot more. Again, totally free. Get it below.

Click the tags below for more articles on similar topics.

Why Angels Invest and Why they Choose Tech

Most Filmmakers need Investors to make their movies. To convince an investor to back in your indiefilm, you need to understand why they invest in anything,

Why should those Rich Tech [People] Invest in your Film, Part 2/7

In order to understand why an investor should invest in your film, you need to understand why investors invest at all. What is an angel investor? What does it take to be a successful angel investor? Why don’t they just buy that Second Third yacht?

To answer the first question, an angel investor is person of means, who generally has a sizable amount of liquid assets and wants to do something more interesting and potentially lucrative than buying stocks or mutual funds. In order to be an accredited investor, an unmarried person must have made at least 200,000 USD for two consecutive years, and be likely to do the same in the current year. If they’re married, that number is more like 300,000 USD. They could also have 1,000,000 in liquid assets, not including their primary residence.

The reason this came about was to protect individuals from being taken by scam artists. The theory behind the income threshold is that if you’re that affluent, you would either have the education or sense to know if you’re being taken, or the means to hire someone who does.

Apart from the aforementioned asset requirement, what does it take to be a professional angel investor? It basically requires two things. Access to capital and deal flow. In layman’s terms, money to invest and projects to invest in. Most of the time, Investors generally assume that about half of their investments will tank and they’ll lose everything due to an inability of the company to exit.

So why do Angel Investors invest? This question is more difficult to answer and actually has several answers that we’ll explore throughout this blog series. But, essentially it boils down to the fact that These investments have the potential to breakout in a big way.

Below is a chart illustrating that point. It has been simplified and assumes very early-stage investments. This chart is generally based on loose feelings and assumptions asserted by many investors I’ve talked to. Just like it’s very difficult to estimate how many films break out, it’s very difficult to estimate how many investments are completely lost. It’s very easy to track winning bets, but much harder to track losing ones. This data is accurate to the dozens of investors I know as to their top-level assumption and the data around films is accurate to my experience as a distributor.

Before we get into any numbers, I should preface I’m not a financial advisor, this is not financial advice, nor am I soliciting for any particular project. This is all conjecture and an extrapolation and explanation of personal experience.

If you’re a filmmaker reading this, you might be thinking to yourself, why are they hunting mythical horses and WTF is a decacorn? A Unicorn is a company valued at more than 1 billion before exiting. If you’re a decacorn, your company is valued at more that 10 billion prior to exit. The reason that you don’t really see it on that pie chart is that it’s only about 1 in 1000 to 1 in 10,000 chance of happening.

So how do investors get their money back from a tech investment? in order for a tech investor to get their money back, generally the company has to be acquired, or go public [IPO.] Films on the other hand, simply need to find profitable distribution, or self-distribute the product. Each exit in each sector have its pros and cons, but in the end the boils down to which is more accessible. So what does the return look like in both cases?

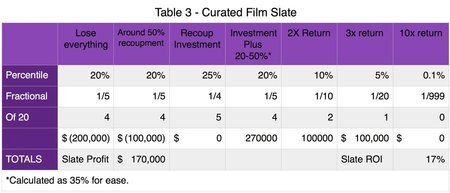

Let's assume an investor invested One Million Dollars across 20 tech sector investments, each investment is made equally. I know that these tables are going to be hard to fully understand, so I’ll have a better data visualizations after table 3.

As you can see the overall ROI is about 85%, which means they nearly doubled their money on the entire portfolio. This is assuming that the investor isn’t completely green and has some idea of what they’re doing, so they make better picks. At some level, this looks very similar to the studio tentpole system. Experts making bets are confident that the ones that hit will cover the losses of the ones that miss. Unfortunately, the numbers don't back that up in the way we would like, partly due to the fact that most angels in the film stlate are not experts, and many filmmakers don't package as well as they should to maximize potential returns.

What does the picture look like for the investor going with no real knowledge of film look like? Well, from my more than a decade marketing and distributing features, here’s about how that would break out.

That’s not Pretty, but it is making a fair amount of negative assumptions about the slate of films. These numbers are assuming they don’t have distribution going in, don’t know what sells, and the film is financed entirely by private equity. The hypothetical investor made the investment at the outset of the project assuming the entirety of the risk. AND the film isn’t well cast with an eye for international sales.

BUT, if you structure your slate look to get at least a letter of intent for distribution a North American distributor and work with an international sales company to ensure the best casting for international saleability. It’s at least possible that you could have a slate that looks more like this.

That’s better, but a well-managed tech portfolio still obliterates it if we go solely by total return potential. The Graph I mentioned is below, to help illustrate my point. Trying to convince a tech investor to break from what they know to invest in something that has less potential to return is a hard sell.

Edit From the Website Transfer: If I were to re-do this, I would probably put the 10x return at more like 0.5-1% as opposed to 0.1%, assuming we account for one in 10 portfolios of 20 films gets a breakout hit, the potential average returns end up around 20-22% depending on which of the pool the breakout comes from. if 2 out of 10 of the portfolios happen to have a breakout it’s closer to an average return of 24-26%

Filmmakers, this is what you’re up against. But fear not, you may have an ace in the hole. In fact you may have more than one. The first ace in the whole is the speed of exit for film projects compared to that of tech startups. Due to that, film projects can return money to the investor faster than a startup would, which matters significantly in increasing the ability for an investor to re-invest and increasing the overall Annual Percentage Rate (or APR) of the investment. Check out part 3 linked below for more information on that.

Part 1:

Why Don’t those “Rich Tech [People]” invest in Your Film?

Part 2: (This Part)

Why Angels Invest, and Why they Choose Tech.

Part 3:

Examining APR: How does Film Stack up to Tech Portfolios?

Part 4:

Breakouts vs Decacorns

Part 5:

Diversification and Soft Incentives.

Part 6:

What’s really stopping Tech Investors from investing in Film?

Part 7:

How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

Thanks for Reading! The numbers in this blog have evolved since I wrote it, but only slightly. If you want to stay up to date on resources, livestreams, and other awesome content I have to offer, you should join my mailing list! You’ll stay up to date on all of my latest content, plus get a free e-book, monthly blog digests, and even a great resource package to help you talk to investors about your film. It’s totally free, so what are you waiting for?

Why Film Needs Venture Capital

Part of creating a sustainable revolution in the film industry is creating a new system of finance. For that, we should look to other industries starting with Private Equity and Venture Capital. Here’s how we do that.

A lightbulb next to a chart outlining the allocation of venture funds in 2011 above a text blurb outlining the data source.

There’s an old joke that goes something like this. Three artists move to Los Angeles, a Fine Artist, a poet, and a Filmmaker. The first day they’re in town, they check out the Mann’s Chinese Theater. When they get there, a wave of inspiration overtakes them. The fine artist says, “This is incredible, I have to draw something! Does anyone have a piece of chalk?” Low and behold a random passerby happens to have one, and hands it over. The fine artist does a beautiful rendering on the sidewalk.

Watching this, the poet says, “I’ve had a flash of inspiration, I must write! Does anyone have a pen and paper?” It happens to be a friendly sort of Los Angeles day, and someone hands over a pen and paper. He writes a beautiful Shakespearean sonnet about his friend’s artistry with the chalk.

The filmmaker says “This is amazing, I’ve got to make a movie about it! Does anyone have any money?”

Even though the costs of making a film have been cut drastically, the joke remains true. I mentioned in my last post that the film world is in need of new money, and that what the film world really needs is something akin to Venture Capital. I think the topic deserves more exploration than a couple paragraphs in a post about transparency.

Venture capitalists bring far more than money to the table. They also bring connections and a vast knowledge of financial and industry specific business knowledge to the table. Essentially these people are experts at building companies, and when you really break it down the best films really are just companies creating a product.

The contribution of connections and knowledge is just as vital to the success of the startup as the money is. We have something somewhat similar in the film world, it’s generally the job of the executive producer to find the money for the film and put the right people in place to run the production and complete the product.

The biggest problem is that good executive producers with contact to money are few and far between, and there are very few connection points between the big money hubs and the independent film world. Filmmakers often don’t only need money, they need to have an understanding of distribution and finance that many simply do not have, and most film schools just do not teach. These positions are generally not full time positions, and most filmmakers just don’t have the money they need to pay people like this. If a venture capital model were to be adapted in film, the firm could link to these experts, and included in the budget for the film at a cost far less than it would normally be, because the person could split their time between all of the projects represented by the firm.

Most people understand that filmmakers need money, what many people do not understand is that there are very valid reasons for an investor to invest in film.A good investor knows that a diverse portfolio is far better than one that focuses solely on one industry. Industries can change and the revenue brought in by any single industry can crash with little notice. Savvy investors will seek to have money in many pots as it really helps to weather through downturns. Film is considered to be a mature industry, and has grown steadily over the past several years, even in the economic downturn. In fact, the film industry is moderately reversely dependent on the economy, so it often does better in economic downturns.

The biggest problem is that most investors just don’t invest in things they don’t know. Investors need to understand an investment before they put money into it.

Film is a highly specialized and inherently risky business. All the money goes away before any comes back, and that can scare off many investors. Especially since they often don’t understand what a good use of resources for a film is and are often incapable of seeing when the project should be stop-lossed as to not lose any more money.

One solution a venture capital firm could bring to this industry that single investors simply cannot is stage financing. Stage financing is a system of finance that is widely used in Silicon Valley. The concept is basically that the investors only release funds once certain checkpoints are met. Single angel investors do not have the time or expertise to act in this way, which is a big part of the reason for the standard escrow model. If a project that makes it through the screening process is only given the money they need for pre production up front, they must pass a review to have funds released for principle photography then it becomes a far more sustainable investment.

Filmmakers may balk at the idea of review, but quite frankly so long as the production is being well managed, they should be able to complete the checkpoints and have the additional funds released with little difficulty, assuming that the right review panel is put in place. The fund itself has every reason to see it’s projects through to completion, so it will only be filmmakers who are not doing their jobs that end up not passing the review process.

Edit: Additionally, there are deals that can be made to help agents and bankable talent feel more comfortable with such a process. This may be a subject of a later blog, and is mentioned in the comments.

Why does the fund have every reason to see films through to completion? Because if the films are not completed, then the fund will have lost all the money it put in with no chance of getting it back. That said, if the production is a disaster, and it’s clear that additional funds would not actually result in a finished and marketable film, then it is far better to cut losses and move on with other projects that have higher potential for revenue.

As mentioned in the last blog, a lack of transparent accounting is also a big issue with investors.

A single filmmaker does not really have the ability to negotiate with a distributor, at least not to a level necessary to resolve the transparency issue. In the relationship, the distributor has all of the power and there’s really very little most filmmakers, especially those just starting out, can do to change that.

But in film as in any industry, money talks. If there were a venture capital firm for film that only worked with distributors who have transparent books, and those distributors could then turn around and propose new projects to the venture capital firm, then some of the issues of transparent accounting could start to change. Many distributors, especially those working in the low budget sphere, are continually raising money for their own projects. So, having a good relationship with a venture capital firm is a big incentive to maintain good books and responsible business practices for filmmakers.

It got listed in the comments section of Black Box that filmmakers shouldn’t necessarily need to have that much business sense, since it takes their whole being to create. Filmmaking is indeed a collaborative effort, and it’s not a director’s job to think about target demographics and marketing strategies. The problem is the people in the film world that truly understand investment and recoupment are few and far between. Many of them also take advantage of filmmakers, as evidenced by the stories of studio accounting from Black Box. Part of what’s needed is the creation of teams that have what it takes to both tell quality stories with high production values, also get the films to market and figure out exit strategies, target demographics, and general budget recoupment tactics.

Many Film Schools just don’t teach this part of the business. Film schools focus everything on how you can make the film, and what it takes to do it, but few of them really give you the ability to actually go raise money. So what’s really needed is a new class of producer that understands the executive side. What’s really needed is a new class of investor that understands what it takes to invest in film, the risks, the rewards, and how it’s diversified. What’s really needed in film is a company that can successfully link the two together, and create a new class of media entrepreneur. What’s really needed is an incubator for independent film with a team that can execute both of these aspects and create a sustainable business model out of it.

Right now no such organization really exists. Legion M has some elements of it, but they miss the new talent discovery elements in favor of risk abatement. Slated works similar to AngelList, but I’m not sure their track record is what it needs to be to justify their price point. I’ve been trying to start one between my various projects with angel groups, Mutiny Pictures, Producer Foundry, and other ventures. It’s clear that the industry is changing, but quite frankly it needs to. The best way to effect the change in practices that need to happen in the industry is to change the way the industry is financed. The entrance of a film fund that operates on principles more akin to the aspiraations of a venture capital firm would do just that, and is exactly why it needs to happen.

If you enjoyed this blog, please share it to your social media. You should also join my mailing list for some curated monthly blog digests built around categories like financing, investment, distribution, marketing, and more. As well as some templates (including a deck template) as well as other discounts, templates, and other resources.

Check out the content tags below for related content

Black Box - a Call for Transparency in Film

The concept that Film Distributors aren’t telling you the whole truth isn’t unknown. However, the problem is deeper than you may realize. Here’s why.

A Black cube on grass in a yard, with the Title “Black Box” in the upper left corner and the subtitle “An In Depth Analysis of ‘Hollywood accounting” in the lower right corner, and logos for Guerrilla Rep media and PRoducer Foundry in the lower left corner.

Photo Credit thierry ehrmann Via Flickr, Modifications made to add title, subtitle, and logos

The process of Filmmaking has been evolving rapidly over the past decade. With the massive change in the availability of equipment, negating the need for tapes or stock, and bringing the professional quality down to a price point thought unfathomable merely a decade ago, the barrier to entry for making a film has been almost completely obliterated. Additionally, education on how to make a film has become widely available, from the massive emergence of film schools to a plethora of information available in special edition DVDs, anyone can learn how to make a film. However, the same cannot be said for Film Distribution. Film distribution is still a black box from where no light or information emerges. There is a very palpable air of secrecy around film distribution, and now that film production has become available for anyone curious enough to seek it, it’s time the same is done for film distribution.

I’ve always loved movies, and I’ve been making films in some fashion for nearly a decade. Even though that’s really not that long, I realized that when I started, camcorders were still fairly rare among middle-class families, and far rarer among high school students. Even the local Access channel worked with three-chip cameras, and those who could afford it swore by the film. That landscape is now nearly unrecognizable, now every other high school freshman carries a 1080p camera in their back pocket anywhere they go. This process has been going on for decades, far longer than my personal experience.

In the 70s, even Super 8 home movies were few and far between. To make a movie in the 70s involved an incredible amount of time, effort, and skill. Many learned by trial and error, with limited training and education often in the form of watching the great films of their eras. In those days, no one went to Film School, because there really weren’t that many of them. You pretty much had to go to New York or LA.

Even those who entered the industry in the 60s and ’70s often went to school for something else. Today, there are 389 Film Schools spread across 43 states, which considerably changes the landscape for Education.

However the same cannot be said for film distribution. Despite the fact that technology has evolved beyond what even the most visionary filmmakers could scarcely imagine back in the 70s. Much of it is still a black box where even the most simple information about budgets and returns are kept largely under lock and key. Studio accounting and net proceeds are just as secret now as they have been since Jimmy Stewart became the first Actor to be a net profit participant back in the 50s.

Even if you made a film that’s being represented by a distributor, many of them will not share accurate information regarding the returns you’ve made. A simple balance sheet is difficult to track down, and even if you can get one it’s often hindered by studio accounting, and the breakeven point is never reached, so the filmmaker never sees his or her share in the net proceeds, also known as profit participation. If filmmakers don’t make money making films, then all they have is an expensive hobby that is unsustainable in the long term. The problem is so vast that even Star Wars Episode 6 never made a profit. Even if they can get their first project bankrolled, unless they can make a profit on their film it is unlikely that they will get to make another one. In the independent film world, most times if the producer never sees their share in the net proceeds, then neither does the investor who footed the bill.

If the investor doesn’t see profit, then they won’t be an investor for long. Unlike the filmmaker, most of them won’t continue to do this just for the vision. The first thing any savvy investor will tell you is that they only invest in what they know. And while they may now be easily able to find information on the process of making the film, the metrics measuring the performance of independent films are unclear and almost always unreliable. If an investor can’t decode and project revenue through clearly definable analytics, most of them are far less likely to close an investment deal. Even if they do invest, if they feel like the distributor is not telling them the whole story, they generally won’t invest again.

If the Industry is to change, new money to enter it. The old money is tied up in sequel after sequel, and rehashes of old stories. The movie-going public is fed up with it and want something new, different from the old franchises. This leaves a demand in the industry for quality content that is simply not being filled to the extent it needs to be. In a way it’s similar to the ’60s and early ’70s here in San Francisco when Venture Capital was just starting, there are many talented young people with great ideas, but little business sense.

The studios are entrenched in the old ways of thinking, and behemoth companies don’t adapt well to change. Startups do adapt well to change, and they really can change thought processes through ideas that take hold. The Film Industry is changing more rapidly than ever before, it will likely be just as unrecognizable in another 5 years as it was 10 years ago. Anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The old companies and the old money can’t adapt as quickly as things are changing, so logically we need new ideas and new money to enter the industry and shake things up.

This is exactly the effect that Venture Capital had when the Traitorous Eight left Shockley Semiconductor to start Fairchild, and then left to start other companies that eventually became Silicon Valley. Fairchild was only able to be started due to a new idea that evolved into what is now known as Venture Capital. In order to effect change as quickly as is needed, something similar must happen in the film industry. But Venture Capital can’t enter an industry where the risks are incalculable. Without a more transparent method of accounting, the risks are indeed incalculable.

The industry is evolving more rapidly than ever before. The future is unclear. It’s a wide-open frontier where anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The process of film production has moved out from the dark rooms and light-proof magazines of old and exposed for all to see. It is time for the business side to do the same. It is time for every filmmaker and investor to have a clear understanding of Distribution. It is time for daylight to expose the studios’ accounting practices. It is time for transparent accounting in film.

While there's not a lot an individual can do about the lack of transparency in the film industry as a whole, there are ways that we as individuals can band together to have an impact. Those tactics are some of what I tried to implement at Mutiny Pictures, and what I address in my content, groups, and consulting. One of the goals of porting over my website was to greatly lessen advertising and sales, but check the links below to learn more about ways you can impact not only your career but the industry as a whole. More details on each of the buttons found below.