What you CAN and CAN’T negotiate in an Indiefilm Distribution Deal

Negotiation is a skill, and it takes a while to understand it. Here are some things I’ve seen as an acquisitions agent for a US distributor, as well as from my time as a producer’s rep.

A HUGE part of my job as a producer’s rep has been to negotiate with sales agents and distributors on a filmmaker’s behalf. While I happen to think my contracts are exceptionally fair, most filmmakers tend to do some level of negotiation. However, others can overplay their hands and lose interest. I’ve checked up on some of the ones that did, and they didn’t make it anywhere. So, no matter who you intend to negotiate with here’s a list of what tends to be possible to negotiate.

One thing to keep in mind is your position as a filmmaker. Distributors tend to have more power in this negotiation. Filmmakers do still have power, as you own your film, but it’s important to keep in mind that in many circumstances, they’ll have significantly more options than you will.

It’s also important to note that these contracts are only as good as the people and companies you’re dealing with. So vetting them is important. The link below has more information on that.

Related: How to vet your sales agent distributor.

There are of course exceptions to these rules, but you knowing the general rules will help. Those exceptions are directly tied to the quality and marketability of your film.

What you CAN negotiate

These are things you CAN negotiate, within reason.

Exclusions

Distribution deals are all about rights transfers and sales. In general, you can negotiate a few exclusions to keep back and sell yourself. It’s important to note that you shouldn’t try for too many of these though, as the distributor needs to be able to recoup what they put into your film. Here are some of the common ones

Crowdfunding fulfillment

Website sales

Tertiary regions the film was shot in.

In general, all rights are given exclusively, but crowdfunding fulfillment might need to be carved out so you can fulfill your obligations to your backers. I’ve never had trouble with this one.

Generally, it’s wise to retain the right to sell your film transactionally through your own website using a platform like Vimeo OnDemand or Vimeo OTT. Distributors tend not to utilize these platforms, so they generally won’t have an issue with it so long as they get advisement on release timing AND it’s only available on said platform transactionally. That is to say, people must pay to purchase or rent the film.

If the film was shot in a very minor territory like the Caribbean, Paraguay, parts of Africa, or maybe parts of the Philippines, it might be possible for you to retain those territories and sell the film yourself. Be careful with how many of those you do.

Marketing Oversight (Home Territory)

Pretty much no matter what territory you’re from, you have some pretty meaningful ability to negotiate additional marketing oversight. This is not an unlimited right, however, and it’s common that final say will remain with the sales agent or distributor. It’s important to do your diligence on how they’ve used that oversight in the past.

Term (To an extent)

If a Distributor or sales agent brings you an agreement with a 25-year term and no MG, walk away. If a Distributor tries to get a 12-15 year term, try to get them down to 10. That’s the industry standard for what we work on.

Exit Conditions (to Some Extent)

You need to make sure that you have aa route out if things go sideways. In general, you need a bankruptcy exit, and I would push for an option to exit on acquisition of the distributor, or if a key person leaves.

What you CAN’T GENERALLY negotiate

(but should probably look out for)

Here’s what you generally can’t negotiate. There are exceptions to how much you can negotiate this, but no matter what these are things you need to fully understand.

The Payment Waterfall

I wrote about the waterfall fairly extensively in the related blog linked below. The biggest issue is that most distributors start taking their commissions BEFORE they recoup their expenses. I understand how and why they do it, but it’s generally not the best.

The biggest negotiation you MIGHT be able to get is what’s known as a producer’s corridor, which effectively helps you get a small amount of money from the first sale. Generally you’ll be placed (essentially) in line with the distributor or sales agent, which means it will take significantly longer for them to recoup their expenses. That said, any way you slice those numbers, you still get paid more.

Related: Indiefilm Distribution Payment Waterfalls 101

Related: The Problem with the Film Distribution Payments

Recoupable Expenses

Recoupable expenses are money a distributor or sales agent invest into the marketing of your film. They generally have to get this back before paying you. The exception above is notable. Generally, there is little ability to negotiate this but you should make sure you get the right to audit at least once per year.

Related: What is a Recoupable Expense in Indiefilm Distribution

Payment Schedule

The payment schedule is how often you receive Both a report and a check. In general, they start out quarterly and move to semi-annually over 2 years. There are exceptions, some of my buyers report monthly. However, in general, after 2 years most of the revenue has been made, and the reports will continue to get smaller and smaller.

DON’T EVEN BRING THESE ONES UP

These are issues you just can’t bring up. The distributor might walk away if you do.

Their Commission

Don’t bring up the sales agent’s commission. You probably don’t have the negotiating power to alter it beyond the corridor I mentioned above.

EXCLUSIVITY

I wrote a whole blog about this linked below, but the basics of it are that we’re essentially dealing with the rights to infinitely replicate media broken up by territory and media right type. The addition of exclusivity is the only way to limit the supply, which is the only reason the rights to the content have any value at all.

DIRECT ACCESS TO THEIR CONTACTS.

These contacts are generally very expensive to acquire, and the entire business model of the sales agent or distributor relies on maintaining good relationships with them. No distributor is ever going to give this to you. They’ll get very annoyed about you even asking.

Thanks so much for reading! If you think that this all sounds like a bit much, and would rather have help negotiating, check out Guerrilla Rep Media’s services which include producer’s representation. your film using the button below. If you need more convincing, join my email list for free educational and news digests and resources on the entertainment business which include an investment deck template, a contact tracking template to help you keep track of the distributors you’re talking to, and a whole lot more.

CHECK THE TAGS BELOW FOR MORE CONTENT

How COVID-19 Affected the Indie Film Industry

COVID-19 affected the entire world. To some degree, it still affects us all. Here’s 2023 update to some estimations I made in 2020 as to the effects of the pandemic on the industry.

Many Filmmakers, like everyone else affected by COVID-19, are itching for some level of a return to normalcy. Unfortunately, like many others think that there may never be a full return to normal. It may well end up as a pre-COVID and a Post COVID period. Similar to how the world changed before and after the great depression, 9/11, The internet, or World War II. Societal traumas tend to leave lasting scars, and that tends to effect the market as a whole and certain industries in meaningful ways. So let’s look at what one executive producer thinks is likely to happen in the film industry as a result.

2023 Update: I put some self-reflection on this blog commenting on how I think my predictions were, and adding more context to what’s happening in 2024 and beyond.

1. The Majors will bounce back quickly

Historically, the film is industry mildly reversely dependent on the economy. It remains one of the cheapest ways to get out and one of the best ways for families to bond while in isolation. The most unpredictable part about this recession’s likely impact on the film industry is the much greater presence of free or cheap entertainment options available right now as compared to the past.

In any case, A significant amount of the pain that’s likely to be felt from this crash is going to be on the lower end of the spectrum. Right now many of the major studios are already gearing up for their next projects since the projects they have will either be released ahead of schedule while people are quarantined or they’ll need to find alternative release plans.

2023 Update: This was right. The majors bounced back quickly. They may not bounce back as quickly from the strikes though.

2. Freelancers will be hurt in the short term.

There’s no sugarcoating this. Freelancers are going to be hurt in the short term. Government stimulus may help, but won’t solve the issue. If you’re in a position to help out by hiring someone to help with your web maintenance or other jobs they can do in isolation, you should do so.

As this crisis continues to drag on, it’s really important we band together as a community and help each other to get work made, even if it ends up making many of us less money than it normally would.

2023 Update: I was wrong, it wasn’t just freelancers that were hurt. As Aide dries up we’re likely to see a lot more pain on the lower 3 quintiles of the economic spectrum. I think this will hurt the entertainment industry as we’re a mass-market product that still only makes significant margins from transactional sales. I’m not sure film is still reversely dependent on the economy, and I’d write a blog about it if someone comments.

3. SVOD Surge

Given people are going to be locked at home with less money than normal and lots of time, we can expect to see viewership and subscriptions to Subscription Video on Demand platforms go up significantly. Not all of these new subscribers will cancel when we return to the new normal. I’m not the only one seeing this, it looks like development and acquisitions are on the rise form many of these people.

It’s very possible that the balance of power between distributors and creators could see a minor shift in the coming months as distributors are going to need more content and the current embargo on production in many states, regions, and territories might cut down on the glut of content that’s been driving down acquisition prices recently.

2023 Update: The consolidation in streaming platforms ended up keeping license fees for the major streamers as low as they were pre-pandemic. It’s unlikely that trend will get much better any time soon.

4. AVOD Surge

Given the general financial issues that were facing the majority of Americans prior to this recession, many may seek to cut recurring subscription services. This may well give rise to AVOD platforms like TubiTV and PlutoTV. I bet Fox is really happy that they bought Tubi right about now.

2023 Update: This was very much true, but the amount of consolidation in the AVOD space is looking like there will be a royalty cut due in part to advertisers tightening their belts. This will cause a lot of problems for indie productions.

5. TVOD Plummets

Transactional VOD hasn’t been healthy for quite a while. If people are hurting for money, it’s unlikely they’ll continue to buy movies one at a time when there are so many films that are available for free or with a low subscription cost. This might not happen immediately, but as the crisis wears on and belts get tighter the TVOD crunch might well continue to worsen.

2023 Update: This one was right on the money. IT’s a rough time for micro-budget films outside of SVOD and AVOD.

6. Presale Surge

Given that we’re likely to see a surge in demand for content right as equity markets are drying up we may well see a surge in presales from distributors in order to fill the gap. This is somewhat speculative, but there is ample historical precedent, most recently in 2008 after the economic meltdown. However, it should be noted this can only go so far given production embargos.

2023 Update: Presales did surge, and they’re still growing for small and midsize films. I’m negotiating a few right now.

7. Theaters may fold at a high rate

Theaters have been in trouble for quite a while. Independent theaters have been very hard hit, but even giants like AMC may end up closing many of their locations instead of re-opening them. The possible Amazon Acquisition of AMC is really quite interesting for the entire landscape. Drive-throughs also seem to be seeing a bit of a resurgence.

2023 Update: Some indies folded, the chains largely survived, although some smaller chains took a haircut. Luckily, theatrical exhibition is still around.

8. Rise of legal simulstreaming

People are feeling lonely and isolated. Film is an inherently social medium. Given we can’t go to the theater as we did before, we might end up seeing the rise of simulcasts for consumers to watch content with their friends. This is something that happened with the Netflix computer App, and Alamo Drafthouse starting virtual streamings limited to certain territories is quite an interesting development.

2023 Update: Sadly I was wrong about widespread simulstreaming, but I am aware that it happened with families via zoom a lot at peak quarantine.

9. Death of DVD greatly Hastened

It’s no secret that physical media (DVD/Blu-Ray) has been in trouble for a while now. Now that it’s been confirmed COVID-19 can live on plastic (like a DVD case) for several days, I can see consumers being even more hesitant to buy movies like this when there are so many options available on Streaming for free.

2023 Update: I was right about this one, although there’s a bit of a nostalgic re-emergence of rental stores going on so there may still be a very limited niche market for physical media.

10. Easier Microbudget sales for a time.

I’ll end on a cheerier note for Most of my readers. Acquisitions seem to be picking up since so many catalogs are being watched much more quickly than originally expected. This spells an opportunity for many filmmakers.

2023 Update: It was easy for a little bit, but the WGA (And probably SAG) strike may still represent an opportunity for micro-budget filmmakers. That said, I stand in solidarity with the Union and I think the cause is just, but I don’t really think micro-budget films are similar enough to be called competition, so let’s get those low-budget films out there so we can swell the ranks of the guilds.

If you want someone to help you sell your movie, track down a presale, or strategize how to market your movie Check out Guerrilla Rep Media Services below.

Also If you’re not convinced about Guerrilla Rep Media Services yet, grab my Free Film Business Resource pack for an ebook, a whitepaper, an investment deck template, and a whole lot more.

Check out the tags below for more related content.

Filmmakers Glossary of Film Investment Terminology

It’s hard to raise funding for a film, and the contracts get confusing quickly. Here’s a glossary to help you understand the mountain of paperwork you’ll need to sign to get your film financed. This blog doesn’t mean you don’t still need a lawyer (I’m not one, and this isn’t legal advice), but it will help you understand the paperwork you’re sent.

Last week I laid out a glossary of general-use film business terms, but the blog ended up a bit too long and dense to be a single post. So, I broke it into two. Last week was the basics of business terms, this week is the next level, and focuses entirely on investment terms. Some of these may seem tangential and unnecessary, however if your goal is to close an investor, you’ll need to thoroughly speak their language. If there’s something you don’t see here, check out last week’s blog here. I’m not a lawyer, this isn’t legal advice, and you should have a solid attorney on your team before trying to close an investment round. With that out of the way, let’s get started.

Capital

While many types exist, The term most commonly refers to money.

Liquid Capital

Money that can be spent immediately, or near immediately. Non-liquid capital would be considered something like real estate holdings which would first need to be liquidated in order to sell.

Principle

In finance: it’s general the initial capital investment or the remaining balance on a debt.

Interest

A percentage fee is added on to the principle of a loan or line of credit.

Compound interest

Interest on the principle of the loan and interest.

Simply: interest on interest.

High-Risk Investment

An investment where an investor may lose most or all of the money they put in. Independent Films are always high-risk investments

Securities and Exchanges Commission (SEC)

The main financial regulatory agency in the United States. It oversees most forms of investment.

Accredited Investor

A person of means who is generally considered to have enough business know-how to appraise an investment, pay someone to appraise it for them, or who wouldn’t be completely destitute from taking a high risk-gamble. As of the date of this publishing, according to the SEC the investor must meet either (NOT both of) the income or net worth requirement in order to be considered an accredited investor.

Income Requirements

1.If filing individually, a person must have made 200,000 USD a year for the past 2 years, and be likely to do the same this year.

2.If filing Jointly, a household must have made 300,000 USD a year for the past 2 years, and be likely to do the same this year.

Net Worth.

The investor or household must have 1 million dollars in net worth OUTSIDE of their primary residence.

High Net Worth Individual (HNWI)

Outside the obvious, this term is generally a financial industry term for accredited investor

Edgar Database

A database of high-risk investments maintained by the SEC that is only accessible to Accredited investors and licensed brokerage or investment firms.

Financing Round

A round of financing or funding that is large enough to take an organization or project to the next major milestone. For how this works in film, check out the youtube video I’ve linked below, and the blog linked below that.

Related Video: The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Financing

Related Blog: The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Financing

Business Plan

A document written by an entrepreneur or filmmaker outlining their investment. In the film industry, this document will also often educate the investor on how the industry functions as a whole. This document is also known as a prospectus, but that term is not as commonly used as it once was.

Private Placement Memorandum (PPM)

A document that’s filed with the SEC for investors to consider investing in your project. Frequently an attorney will base this document off of the filmmaker or entrepreneur’s business plan. In most cases, a PPM will be registered with the aforementioned Edgar database for a modest filing fee.

Pro-Forma Financial Statements

Financial documents consisting of an expected income breakdown, cash-flow statement, and top sheet budget to be invaded in the business plan and function as the basis for many of the financial sections of other documents

The Three points above are heavily outlined in my business planning blog series.

Related: How to write an independent Film Business Plan (1/7)

Backed Debt

A secured loan backed by something like a tax incentive or pre-sale agreement.

Unbacked Debt

An unsecured loan, or debt without backing. Generally very high interest.

Financial Gap

The space between what you are able to raise and the amount you need to finish your project.

Financial Markets

A market where stocks, bonds, derivatives, or other securities are bought and sold. Common examples in the US would be the DOW and the NASDAQ.

Film Market

A convention where films are bought and sold primarily by sales agents and distributors. For more, check out the link below.

Related: What is a film market and how does it work?

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

The total value of all newly finished goods in a given country during a set timespan. Most commonly calculated on an annual basis.

Recession

A macroeconomic term signifying a period of a significant decline in economic activity. It’s generally only recognized after two consecutive quarters of down financial markets.

Depression

A severe recession that lasts longer than 3 years and corresponds with a drop in GDP of at least 10%

Bull Market

A market that’s strong and growing. It’s called a bull market as the upward trending graph looks like a bull nodding its head according to some people on Wall Street.

Bear Market

Yes, I spelled that right. It’s a financial market that’s going down, or staying stagnant. The name comes from a bear swiping its claws down. Probably the same wall street guy came up with it.

Thanks so much for reading! If you liked this, please make sure to check out last week’s general financing glossary, as well as my glossary of distribution terms. Also, please share. It helps A LOT.

Filmmakers Glossary of Business Terms

Additionally, make sure you grab my free Film Business Resource Package to get a print ready PDF version of all 3 glossaries.

Check the tags below for more related content.

Filmmakers Glossary of Film Business Terminology.

I’m not a lawyer, but I know contracts can be dense, confusing, and full of highly specific terms of art. With that in mind, here’s a glossary of Art. Here’s a glossary to help you out.

A colleague of mine asked me if I had a glossary on film financing terms in the same way I wrote one for film distribution (which you can check out here.) Since I didn’t have one, I thought I’d write one. After I wrote it, it was too long for a single post, so now it’s two. This one is on general terms, next week we’ll talk about film investment terms. As part of the website port, I’m re-titling the first part to a general film business glossary of terms, to lower confusion on sharing it. It’s got the same terms and the same URL, just a different title.

Capital

While many types exist, it most commonly refers to money.

Financing

Financing is the act of providing funds to grow or create a business or particular part of a business. Financing is more commonly used when referring to for-profit enterprises, although it can be used in both for profit and non-profit enterprises.

Funding

Funding is money provided to a business or non-profit for a particular purpose. While both for-profit and non-profit organizations can use the term, it’s more commonly used in non-profit media that the term financing is.

Revenue

Money that comes into an organization from providing shrives or selling/licensing goods. Money from Distribution is revenue, whereas money from investors is financing, and donors tend to provide funding more than financing, although both terms could apply.

Equity

A percentage ownership in a company, project, or asset. While it’s generally best to make sure all equity investors are paid back, so long as you’ve acted truthfully and fulfilled all your obligations it’s generally not something that you will forfeit your house over. Stocks are the most common form of equity, although films tend not to be able to issue stocks for complicated regulatory reasons and the fact that films are generally considered a high-risk investment.

Donation

Money that is given in support of an organization, project, or cause without the expectation of repayment or an ownership stake in the organization. Perks or gifts may be an obligation of the arrangement.

Debt

A loan that must be paid back. Generally with interest.

Deferral

A payment put off to the future. Deferrals generally have a trigger as to when the payment will be due.

“Soft Money"

In General, this refers to money you don’t have to pay back, or sometimes money paid back by design. In the world of independent film, it’s most commonly used for donations and deferrals, tax incentives, and occasionally product placement. It can have other meanings depending on the context though.

Investor

Someone who has provided funding to your company, generally in the form of liquid capital (or money.)

Stakeholder

Someone with a significant stake in the outcome of an organization or project. These can be investors, distributors, recognizable name talent, or high-level crew.

Donor

Someone who has donated to your cause, project, or organization.

Patron

Similar to donors, and can refer to high-level donors or financial backers on the website Patreon. For examples of patrons, see below. you can be a patron for me and support the creation of content just like this by clicking below.

Non-Profit Organizations (NPO)

An organization dedicated to providing a good or service to a particular cause without the intent to profit from their actions, in the same way, a small business or corporation would. This designation often comes with significant tax benefits in the United States.

501c3

The most common type of non-profit entity file is to take advantage of non-profit tax exempt status in the US.

Non-Government Organization (NGO)

Similar to a non-profit, generally larger in scope. Also, something of an antiquated term.

Foundation

An organization providing funding to causes, organizations and projects without a promise of repayment or ownership. Generally, these organizations will only provide funding to non profit organizations. Exceptions exist.

Grantor

An organization that funds other organizations and projects in the form of grants. Generally, these organizations are also foundations, but not necessarily.

Fiscal Sponsorship

A process through which a for-profit organization can fundraise with the same tax-exempt status as a 501c3. In broad strokes, an accredited 501c3 takes in money on behalf of a for-profit company and then pays that money out less a fee. Not all 501c3 organizations can act as a fiscal sponsor.

Investment

Capital that has been or will be contributed to an organization in exchange for an equity stake, although it can also be structured as debt or promissory note.

Investment Deck (Often simply “Deck”)

A document providing a snapshot of the business of your project. I recommend a 12-slide version, which can be found outlined in this blog or made from a template in the resources section of my site, linked below.

Related: Free Film Business Resource Package

Look Book

A creative snapshot of your project with a bit of business in it as well. NOT THE SAME AS A DECK. There isn’t as much structure to this. Check out the blog on that one below.

Related: How to make a look book

Audience Analysis

One of 3 generally expected ways to project revenue for a film. This one is based around understanding the spending power of your audience and creating a market share analysis based on that. I don’t yet have a blog on this one, but I will be dropping two videos about it later this month on my youtube channel. Subscribe so you don’t miss them.

Competitive Analysis

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. This method involves taking 20 films of a similar genre, attachments, and Intellectual property status and doing a lot of math to get the estimates you need.

Sales Agency Estimates

One of 3 ways to project revenue for an independent film. These are high and low estimates given to you by a sales agent. They are often inflated.

Related: How to project Revenue for your Independent Film

Calendar Year

12 months beginning January 1 and ending December 31. What we generally think of as, you know, a year.

Fiscal year

The year observed by businesses. While each organization can specify its fiscal year, the term generally means October 1 to September 30 as that’s what many government organizations and large banks use. Many educational institutions tie their fiscal year to the school year, and most small businesses have their fiscal year match the calendar year as it’s easier to keep up with on limited staff.

Film Distribution

The act of making a film available to the end user in a given territory or platform.

International Sales

The act of selling a film to distributors around the world.

Related: What's the difference between a sales agent and distributor?

Bonus! Some common general use Acronyms

YOY

Year over Year. Commonly used in metrics for tracking marketing engagement or financial performance on a year-to-year basis.

YTD

Year to Date. Commonly used in conjunction with Year over year metrics or to measure other things like revenue or profit/loss metrics.

MTD

Month to Date. Commonly used when comparing monthly revenue to measure sales performance. Due to the standard reporting cycles for distributors, you probably won’t see this much unless you self-distribute.

OOO

Out of Office. It generally means the person can’t currently be reached.

EOD

End of Day. Refers to the close of business that day, and generally means 5 PM on that particular day for whatever the time zone of the person using the term is working in.

Thanks for reading this! Please share it with your friends. If you want more content on film financing, packaging, marketing, distribution, entrepreneurialism, and all facets of the film industry, sign up for my mailing list! Not only will you get monthly content digests segmented by topic, but you’ll get a package of other resources to take you film from script to screen. Those resources include a free ebook, whitepaper, investment deck template, and more!

Check the tags below for more related content!

The 6 Steps to Negotiating an Indiefilm Distribution Deal

If you want the best distribution deal for your independent film, you have to negotiate. Here’s a guide to get you started.

Much of my job as a producer’s rep is negotiating deals on behalf of filmmakers. However, now that I’m doing more direct distribution, I’m realizing there are several things about this process that most filmmakers don’t understand. As I tend to write a blog whenever I run into a question enough that I feel my time is better spent writing my full answer instead of explaining it again, here’s a top-level guide on the process of negotiating an independent film distribution deal.

Submission

Generally, the first stage of the independent distribution process is submitting the film to the distributor. There are a few ways this can happen. Some distributors have forms on their website (mine is here) Others will reach out to films their interested in directly. Some will have emails you can send your submissions to. There are a few things to keep in mind here, but in the interest of brevity, just check out the blog I’ve linked to below. There’s a lot of useful information in that blog, but I will say that YES, THE DISTRIBUTOR NEEDS A SCREENER IF THEY’RE ASKING FOR ONE.

Related: What you NEED to know BEFORE submitting to film distributors

Initial Talk

Generally, the next step is for the distributor to watch the film. I have a 20-minute rule, and that’s pretty common. Generally, if I make it through the entire film, I’ll make an offer. If I don’t, I won’t ever make an offer. If I’m requesting a call, I’m normally doing so to size up the filmmaker and see if they’re going to be a problem to work with.

This is not an uncommon move for distributors that actually talk to filmmakers and sales agents. Generally, we want to discuss the film as well as size up the filmmaker before we send them a template contract.

Template Contract

Generally, when we send over the template contract, it will be watermarked and a PDF so that the filmmaker can understand our general terms. This also won’t have any identifying information for the film on there. We’ll also attach it. Few appendices to the contract can change more quickly than the contract itself. My deliverables contract is pretty comprehensive as of right now, but honestly, I think I’ll pare it down soon as I haven’t had to use much of what’s in there yet.

Red-Lining

The next major step in the process of the distribution deal is going through and inserting modifications and comments using the relevant function on your preferred word processor. Most of the time they’ll send it in MSWord, but you can open Word with pretty much any word processor and this is unlikely to be too affected by the formatting changes that happen as a result of putting the document into pages or open office. That said, version errors around tracking changes do happen, and if you find yourself in that situation comment on everything.

What you should go through and do is make sure track changes are turned on, and then comment on anything you have a question about and cross out anything that simply won’t work for you.

NOTE FROM THE FUTURE: Since someone commented on this at a workshop, I’m aware that Redlining has another historical context in the US, but it is the common parlance for this form of contract markup as well. I’m in favor of negotiating distribution deals, and not in favor of racist housing policies.

Counter-Offers

Generally, distributors and sales agents will review your changes, accept the ones they can, reject the ones they can’t, and offer compromises on others. While there are some exceptions to this framework, after the first round of negotiations, it’s often a take-it-or-leave-it arrangement. If it’s good enough, sign it and you’re in business. If not, walk away.

Quality control

Most sales agents and distributors will have you send the film to a lab to make sure the film passes stringent technical standards. If you have technically adept editor friends, you’ll want them to do a pass first, as each time you go through QC it will cost you between 800 & 1500 bucks. You will need to use their lab, but it’s best for everyone if it passes the first time.

If you need help negotiating with sales agents or just need distribution in general, that’s what I do for a living. Check out my services using the button below. If you want more content like this, sign up for my email list so you can get content digests by topic in your inbox once a month, plus some great film business and film marketing resources including templates, ebooks, and money-saving resources.

Check the tags below for related content

How to Make LookBook for an Independent Film

Decks and lookbooks are not the same. Here’s how you make the latter.

I’ve written previously about what goes into an indie film deck, but as I get more and more submissions from filmmakers, I’m realizing that most of them don’t fully understand the difference between a lookbook and a deck. So, I thought I would outline what goes into a lookbook, and then I’ll come back in a future post to outline when you need a lookbook when you need a deck, and when you need a business plan.

What goes in a lookbook is less rigid than what goes in a deck. It’s also designed to be a more creatively oriented document than a deck. But in general, these are the pieces of information you’ll need in your lookbook. I’ve grouped them into 4 general sections to give you a bit more of a guideline.

You’ll often see the term stakeholder. I use this to mean anyone who might hold a stake in the outcome of your project, be they investors, distributors, or even other high-level crew.

Basic Project Information

This section is to give a general outline of the project and includes the following pieces of information.

Title

Logline

Synopsis

Character Descriptions

Filmmaker/Team bios

The title should be self-explanatory, but if you have a fancy font treatment or temp poster, this would be a good place to use it.

The logline should be 1 or 2 sentences at most. It should tell what your story is about in an engaging way to make people want to see the movie. You probably want to include the genre here as well,

The synopsis in the lookbook should be 5-8 sentences, and cover the majority of the film’s story. This isn’t script coverage or a treatment. It’s a taste to get your potential investors or other stakeholders to want more.

Character descriptions should be short, but more interesting than basic demographics. Give them an heir of mystery, but enough of an idea that the reader can picture them in their head. Try something like this. Matt (white, male, early 20s) is a bit of a rebel and a pizza delivery boy. He’s a bit messy, but nowhere near as bad as his apartment. He’s more handsome than his unkempt appearance lets on, If he cleaned up he’d never have to sleep alone. But one day he delivers pizza to the wrong house and gets thrust into time-traveling international intrigue.

Even that’s a little long, but I wasn’t actually basing it on a movie, so tying it into the film itself was trickier than I thought it would be. That would be alright for a protagonist, but too long for anyone else.

Filmmaker and Team bios should be short, bullet points are good, list achievements and awards to put a practical emphasis on what they bring to the table DO NOT pad your bio out to 5000 words of not a lot of information. Schooling doesn’t matter a lot unless you went to UCLA, USC, NYU or an Ivy League school.

Creative Swatches

These are general creative things to give a give the prospective stakeholder an idea of the creative feel of the film. They can include the following, although not all are necessary.

Inspiration

Creatively Similar Films

Images Denoting the General Feel of the Film

Color Palette

The inspiration would be a little bit of information on what gave you the vision for this film. It shouldn’t be long, but it definitely shouldn’t be something along the lines of “I’ m the most vissionnarry film in the WORLD. U WILL C MAI NAME IN LAIGHTS!” (Misspellings intentional) Check your ego here, but talk about the creative vision you had that inspired you to make the film. Try to keep it to 3-4 sentences.

Creatively similar films are films that have the same feel as your film. You’re less restricted by budget level and year created here than you would be in a comp analysis, that said, don’t put the Avengers or other effects-heavy films here if you’re making an ultra-low budget piece. I’d say pick 5, and use the posters.

Images denoting the general feel of the film are just a collection of images that will give potential stakeholders an idea of the feel of the film. These can be reference images from other films, pieces of art, or anything that conveys the artistic vision in your head. This is not a widely distributed document, so the copyright situation gets a bit fuzzy regarding what you an use. That said, the stricter legal definition is probably that you can’t use without permission. #NotALawyer

The color palette would be what general color palette of the project. This is one you could leave out, but if there’s a very well-defined color feel of the film like say, Minority Report, then showing the colors you’ll be using isn’t a terrible call, Also,, it's generally best to just let this pallet exist on the background of the document on your look book.

Technical/ Practical swatches

This section is a good indicator of what you already have, as well as some more technical information about the film in general. It should include the following.

Locations You’d like to shoot at

Cities You’d Like to shoot in

Equipment you plan on using

Photos are great here, if you use cities or states include the tax incentives for them, The equipment should only be used if it’s the higher end like an Arri or Red. If you’re getting it at a fantastic cost, you should mention that here as well. People tend not to care about the equipment you’re using, but if you’re going to put it in any pitch document, this is the one.

Light Business Information

The lookbook is primarily a creative document, but since most of the potential stakeholders you’re going to be showing it to are business people, you should include the basics. When they want more, send them a deck.

Here’s what you should include

Ideal Cast list & Photos

Ideal Director List

Ideal Distributors

These are important to assess the viability of the project from a distribution standpoint. It can also affect different ways to finance your film. If your director is attached, don’t include that. If you have an LOI from a distributor, don’t mention potential distributors. Unless your film is under 50k, don’t say you won’t seek name talent for a supporting role. You should consider it if it’s even remotely viable.

If this was useful to you but you need more, you should snag my FREE indiefilm resource package. I’ve got lots of great templates you get when you join, and you also get a monthly blog digest segmented by topic to make sure you’re informed when you start talking to investors. Click below to get it.

What Filmmakers NEED to Know BEFORE Submitting to Distributors

As distributors, we get dozens of submissions a week. Here’s how you can make sure to stand out.

I get a lot of submissions to my portal in the upper right of my website. In fact, it’s how I get most if not all of the films I distribute. As such, I’ve noticed some trends filmmakers tend to have. So as with most recurring things that happen to me in the business, I decided to write a blog about it.

1. Yes, we do need a screener and the password.

If we’re going to distribute a film, we need to watch it. Generally, that’s the first step, not the second or the third. We’ll probably want to talk to you before we sign you, but the first step is to see if the product is any good. It’s easiest for us to be impartial about the market potential of your film if we watch it cold first. I always get back to people who submit, and I do a strategy call before I sign them,

We understand that you’re sensitive about your intellectual property and that your film is your baby. The good ones among us also expect that you’ll do some legwork and diligence on use before you submit. Don’t make us email you for a password. I use google forms to manage my submissions portal, and only I have access to it. The only reason I didn’t create more of a custom solution is that the security protocols for G Suite apps are better than most anything else that would be cost-effective to use or create.

2. Get a Vimeo Subscription

While I like Youtube for a lot of reasons, reviewing films is not one of them. Vimeo’s player is higher quality than youtube’s, and when I’m reviewing a film one of the things I’m looking for is if there are likely to be any expensive quality control problems. Youtube makes that very difficult to gauge, due to the compression of the files that go up on the site.

Also, it looks cheap to send an unlisted youtube link. Vimeo isn’t expensive, and there will be costs associated with distribution that get passed on to the filmmaker at least in part. If you can’t pay for a Vimeo subscription, we worry about the viability of your business.

3. We generally only watch a film once, if we watch the whole thing at all.

I get a fair amount of submissions to my portal, most of which I decline to represent. A lot of the films I decline are ones I stopped watching after 20 minutes. I give every film 20 minutes, but if it doesn’t grab me in that time I don’t continue to watch it, and if I don’t continue to watch it it’s an automatic decline.

Most of the time, if I watch a film all the way through, I’m going to represent it. There have been exceptions due to some self-imposed content restrictions.

That being said, we have to watch A LOT of movies. We almost never watch them twice. So don’t keep submitting with minor changes. If it’s a decline, it’s a decline. Also, don’t submit it until it’s where you need it to be.

As an aside: If you’re going to make changes to the film after we’ve made an offer, we’ll probably rescind the offer unless you talk to us about it. We made an offer to the film we saw. If you make substantive changes, it’s not going to endear you to us.

Films Brought to Market by Guerrilla Rep Media

4. Festivals provide some level of validation but are far from the be-all and end-all of the film.

Similar to how festivals aren’t likely to get you distribution (discussed in this blog, right here.) they’re far from the only thing that matters to distributing the film. The laurels mean less than you probably think they do to the sales of a film. Unless it got into one of the top festivals, it’s not going to help you as much as you may think. For more, read the link below.

Related: Why you won’t get Distribution from your film festival

5. Yes, we do need to know about your social media, but not why you think.

Yes, I ask about your social media. Sure, it has a bit to do with assessing your total reach, but it has more to do with your engagement in your community. Distribution on a budget requires working together with filmmakers.

Also, it helps us know your voice is authentic. We, distributors, do tend to have favored niches, but we also want to make sure that the films we’re distributing are authentic. Your being heavily involved in relevant online communities is a great indicator of that authenticity.

I think I might write more on why distributors care about social media, but I definitely will if someone tweets to me about it or comments below.

Anyway, thanks so much for reading this blog! If you learned something, but still want more, you should grab my FREE Indiefilm resource Package. It’s got an e-book on the film biz, a whitepaper on the industry, templates to help you track your contact with distributors, plus a while lot more! Check it out via the button below!

5 Takeaways from AFM 2018

A legacy port of my breakdown of the 2018 American Film Market.

I’ve been going to the American Film Market® for 9 years now, and I’ve been chronicling what’s going on with the market in many ways from podcasts to blogs and even a book or two. So given that AFM® 2018 wrapped up yesterday, I thought I would do something of a post-mortem. While I’ll outline my feelings on the whole thing in this blog, the long and short of it is that the state of the American Film Market is mixed

But before I dive into it too deeply, I’d like to say this. My vantage point on this is purely my own, and subject to the flaws that one would expect from experiences of someone only attending the market for a few days this year. I went on an industry badge because I simply needed to take a few meetings to check in on things I’ve already placed with Sales Agents, as well as shop a couple of my newer projects to the people I prefer to do business with.

I considered exhibiting this year but decided against it after hearing how slow Cannes was in May, as well as the massive drop in buyers AFM Experienced last year. We’ll see how that changes next year. One last note, I wrote this blog in traffic in LA, while my wife drove. I normally don't publish first drafts, but it's time-sensitive, so apologies for any typos.

So without Further Adieu, let’s get into the post-game.

1. Buyer numbers appear to be up, and they’re buying

Word in the corridors last year was that AFM went from around 1800 buyers in 2017 to around 1200 buyers in 2017. After talking to a few sales agents who shall remain nameless, it appears that the total buyer count at this year’s AFM is somewhere in the vicinity of 1325. While walking the corridors I definitely saw a lot more green badges than last year.

Not only were there more buyers there. It appears that they’re actually buying films. I heard several sales agents remarking that they had closed multiple sales at the market, and the buyers were sticking around much longer than they have in years previous. Overall, this is good for the market, especially given that for many years almost all of the business was done in follow-up not actually during the market, especially for smaller-budget films.

2. Exhibitor numbers appeared to be down

In previous years, both the second and third floors of AFM were packed with smaller sales agencies, This year, only the third floor was booked and even then it seemed as though fewer offices were booked. Also, it appeared that many of the offices on the 8th floor seemed to be vacant.

After talking with a few exhibitors, it appears likely that this trend is going to continue next year. Several I talked to were unsure of whether or not they would continue to exhibit at AFM. Although we’ll see if new names come up to take their places.

3. The Entirety of the Loews required a badge to access

This made a lot of headlines prior to the market. I was hesitant to believe that this would be a good thing for the market, particularly for the high priced film commission exhibitors on the 5th floor. I only showed up to the market on Saturday, but apparently it was extremely quiet for the days preceding it. The market seemed somewhat slow to me, but mildly busier than I expected it to be on Saturday, and, but began steadily dropping off on Sunday and Monday, and Tuesday was VERY slow, even by the generally slow standards of what is functionally the last day of the market.

Word on the street is that many of the regular exhibitors on the 5th floor were not too happy with it, especially for the first few days. Although I’ll keep my sources on that anonymous. One notably missing 5th-floor exhibitor was Cinando. It’s possible they moved, but the spot that they normally occupied was vacant. This could be due in part to the growing prominence of MyAFM.

In some ways, it was nice, though. It was never too hard to find a seat, and once you got into the building there were no additional security checks. Not sure if that makes up for the drawbacks though.

4. The Location Expo on the 5th floor was fantastically useful, but under-attended

AFM opened one of the Loews Hotel Ballrooms for use by film commissions and specialty service providers starting on Saturday. It was really useful to be able to talk to various commissions and compare incentives. However, there very few times I saw more than a handful of people there, and I dropped by at least 8 or 9 times because of various sorts of business I had to do with some of the vendors in the rooms. (More soon)

Overall I hope to see it again, but I can’t help but think it would be more useful to all involved if it were in an area that did not require a badge to check out.

5. Early Stage Money exists there (For the Right Projects

I was surprised to see how much traction my team got for an early stage project, despite the fact it has a first time feature director. Admittedly, we came in with a good amount of money already in place, and it’s a good genre for this sort of thing but the fact that there might be a decent amount to come out and report in blogs early next year.

Thanks so much for reading! If you haven’t already, check out the first book on film markets, written by yours truly. Also, join my mailing list for free film market resources so you’re ready for future film markets.

All opinions my own. AFM and the American Film Market are registered trademarks of the Independent Film and Television Alliance (IFTA) This article has not in any way beed endorsed by the IFTA, AFM, or any of its affiliates.

Why Genre is VITAL to Independent Film Marketing & Distribution

If you’re going to make a movie, you need to be able to make an independent film, you need to

This is a topic that’s a little basic, but it’s a fundamental building block of understanding how to market your film. So I thought I would do a breakdown of why genre is so important to independent filmmakers in terms of marketing and distribution. I do touch on in my book The Guerrilla Rep: American Film Market Distribution Success on No Budget, but even there I only cover it in a sense as it pertains to the market. Let’s get started.

Before we begin, we should talk about what a genre actually is. At its core, the genre of your film is primarily a simple tool for categorizing how your film compares to other films. It’s a broad bucket of similar elements that lump films together in a way that makes it easier to sell them and easier to convey the general experience of a film succinctly. Knowing this will inform everything else on this list.

Generally, there are both genres and sub-genres. Sub-genres can generally pair with any genre, but some pairings work better than others. Here’s a somewhat complete list of genres and sub genres. Genres tend to focus on plot elements and overall feel whereas Sub Genres also have more to do with themes or settings.

Genres

Action

Horror

Thriller

Family

Comedy

Drama

Documentary

Sub-Genres

Adventure

Sci-Fi

Fantasy

Crime

Sports

Faith Based

LGBT

Romance

Biographical

Music/Musicals

Animated

So Why is Genre So Effing Important?

Genre provides a general set of guidelines for filmmakers to follow when crafting a story.

Since there are certain elements that are inherent in any particular genre, understanding the tropes of any particular genre can be very helpful in crafting your narrative and in shooting your film. If you know you’re shooting an action film, then there had better be fight scenes, shootouts, and car chases. If you’re making a thriller, there should be a lot of suspense. If you’re shooting a horror, a good amount of your budget will go on buckets of blood. Knowing the tropes in advance can really help frame your story and what you need to shoot your film.

Genre categorizes it for potential customers

As mentioned above, genres are simply categorizations of similar elements of a film. As such, certain viewers will develop an affinity for a certain genre. Some people will like some genres more than others. Sometimes a viewer will be in the mood for one genre, but not in the mood for another. Kind of like how sometimes you’re craving Mexican food, and other times you’re craving Chinese.

Genre helps to find an audience for the film

Think of this as the reverse of the point above. If your film has a well-defined genre, it can be great for discovery by the audience that’s seeking it out. Again, think about the food example. If you’re a Mexican food restaurant in an area where the community is all huge fans of Mexican cuisine, you’re likely to do well. However, if you’re a barbecue joint in a city known for its insanely high levels of Veganism, you might be in for a rough go of it. Of course, this kind of ignores the problem of oversaturation but there’s only so much I can tackle in 600-800 words.

Genre categorizes your film for Distributors and sales agents

Distributors and Sales agents understand the issues above. In addition, they often build a brand around certain genres so that there’s a high degree of audience recognition from them. Buyers and distributors often continually serve the same end viewer, and as such their brand is particularly important, and they often seek a similar sort of film time and time again. Think about the difference between the programming on Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network, or the difference between Comedy Central and MTV.

Sales agents generally develop deep relationships with the same buyers. As such, they become acutely aware of that buyer’s brand, and the sort of content they normally buy. As such, that’s the sort of content they look to acquire.

What happens if I cross-Genres?

So this is somewhat beyond the scope of this blog, but it’s a point that should be made and I don’t think I could spend an entire blog on it. So keep in mind that cross-genre is different than a genre and a sub-genre. A Cross Genre would be a horror comedy or an action thriller. Those are two examples that generally work, at least in the right circumstances. Other genre-crossing like Action Drama or Family Horror probably don’t work so well.

Here are a couple of things to keep in mind about going cross-genre.

It doesn’t add to the audience it limits it

If you make a film that’s both horror and comedy, it doesn’t sell to people who like either Horror and Comedy, it generally only appeals to people who like BOTH horror AND Comedy. So instead of expanding your horizons, it limits them. However, people who like both of these genres are going to be far more likely to really enjoy your film, just because they don’t get as much horror/comedy content as they might like. That said, getting to these people can be both difficult and expensive.

If done poorly, it confuses the message.

As you can see from the later two examples above, if you cross genre poorly it can be very creatively limiting. A horror family movie doesn’t sound like it would be possible to do very well. I know that Indiana Jones and the Temple of doom had elements of this, as did Gremlins, but The Temple of Doom was primarily an Action Adventure movie, and Gremlins would be very difficult to package in this day and age.

If you'd like to learn more about film marketing and distribution, you should join my mailing list. You'll get access to a FREE set of film market resources, as well as several digests over a few months of articles just like this one, organized by topic, delivered directly to your inbox.

Check The tags below for related content

The 7 Essential Elements of A Strong Indie Film Package

If you want to get your film financed by someone else, you need a package. What is that? Read this to find out.

Most filmmakers want to know more about how to raise money for their projects. It’s a complicated question with lots of moving parts. However, one crucial component to building a project that you can get financed is building a cohesive package that will help get the film financed. So with that in mind, here are the 7 essential elements of a good film package.

1.Director

As we all know, the director is the driving force behind the film. As such, a good director that can carry the film through to completion is an essential element to a good film package. Depending on the budget range, you may need a director with an established track record in feature films. If you don’t have this, then you probably can’t get money from presales, although this may be less of a hard and fast rule than I once thought it was.

Related:What's the Difference between an LOI and a Presale?

Even if you have a first-time director, you’ll need to find some way of proving to potential investors that they’ll be able to get the job done, and helm the film so that it comes in on time and on budget

2. Name Talent

I know that some filmmakers don’t think that recognizable name talent adds anything to a feature film. While from a creative perspective, there may be some truth to that, packaging and finance is all about business. From a marketing and distribution perspective, films with recognizable names will take you much further than films without them. I’ve covered this in more detail in another blog, linked below.

Related: Why your Film Needs Name Talent

Recognizable name talent generally won’t come for free. You may need a pay-or-play agreement, which is where item 7 on this list comes in handy.

3. An Executive Producer

If you’re raising money, you should consider engaging an experienced executive producer. They’ll be able to help connect you to money, and some of them will help you develop your business plan so that you’re ready to take on the money when it comes time to. A good executive producer will also be able to greatly assist in the packaging process, and help you generate a financial mix.

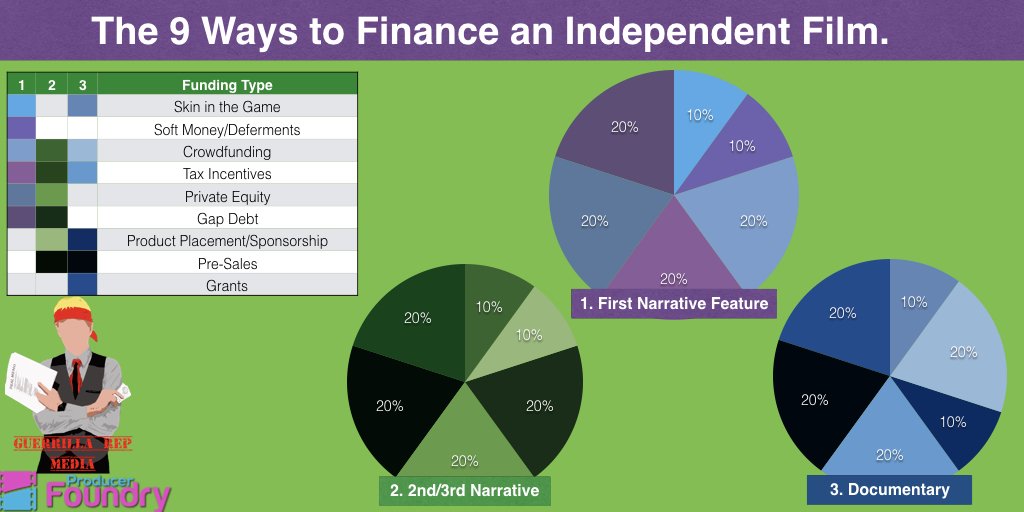

Related: The 9 Ways to finance an Independent Film.

I do a lot of this sort of work for my clients. If you’ve got an early-stage project you’d like to talk about getting some help with building your package and/or your business plan I’d be happy to help you to do so. Just click the clarity link below to set up a free strategy session, or the image on the right to submit your project.

4. Sales Agent/Distributor

If you want to get your investors their money back, then you’re going to need to make sure that you have someone to help you distribute your independent film. The best way to prove access to distribution is to get a Letter of Intent from a sales agent. The blog below can help you do that.

Related: 5 Rules for Getting an LOI From a Sales Agent

5. Deck/Business Plan

If you’re going to seek investors unfamiliar with the film industry, you’re going to need a document illustrating how they get their money back This can be done with either a 12-slide deck, or a 20-page business plan. I’ve linked to some of my favorite books on business planning for films below.

6. Pro-Forma Financial Statements

Pro forma financial statements are essentially documents like your cash flow statement, breakeven analysis, top sheet budget, Capitalization Table, and Revenue Distribution charts that help you include in the latter half of the financial section of a business plan.

There’s a lot more information on these in the book Filmmakers and Financing by Louise Levinson. I’m also considering writing a blog series about writing a business plan for independent film. If you’d like to see that, comment it below.

7. Some Money already in place

Yes, I know I said that you need a package to raise money, but often in order to have a package you need to have some percentage of the budget already locked in. Generally, 10% is enough to attach a known director and known talent. If you’re looking for a larger Sales Agent then you’ll also need to have some level of cash in hand.

This is essentially a development round raise. For more information on the development round raises, check out this blog!

Thanks for reading, for more content like this in a monthly digest, as well as a FREE Film Market Resources Package, check out the link below and join my mailing list.

Check the tags below for related content.

Understanding the difference between an LOI and a Pre-Sale

A Letter of Intent (LOI) and a Pre-Sale are not the same thing, here’s what they are before you ask a sales agent or distributor for one.

A few weeks back I did a post on how to get a Letter of Intent from a Sales Agent. You can read that post here. However, I realized it might not be a bad idea to step back and examine the differences between a Letter of intent and a Pre-Sale. While I touch on it in the Rules for Getting a Letter of Intent blog, It seemed like the topic was worth a little bit more explanation.

At its core, the primary difference between the two is that a pre-sale is a document that has a tangible value, and an LOI does not. It’s a document that says once you deliver the completed film to the sales agent/distributor you will receive a check for an agreed-upon amount. Generally, they’ll come coupled with a completion bond. If you get a presale from the right sales agent/distributor, then this document is serious enough that you could take it to an entertainment bank and take out a loan against it.

A letter of intent is a much less serious document. It essentially guarantees that a sales agent will review a film once it’s completed and if it passes quality concerns, they’ll make an offer to represent the film at that point in time. This document has no monetary value but proves to investors that you have access to distribution.

RELATED: 5 RULES FOR AN LOI FROM A SALES AGENT

The reality is that while pre-sales still happen, the likelihood of getting one isn’t very high for the vast majority of filmmakers.

In an ideal world, every filmmaker would be able to get presales and fund most if not all of their movie on them. Unfortunately, we do not live in an ideal world. With the glut of content currently being produced, most filmmakers should consider themselves lucky to get a Letter of Intent.

The reason a Sales Agent or a Distributor would pre-buy a movie is so they know they’ll be able to fill the programming slots when the time comes. It used to be that if they pre-bought content, they could get it at a lower cost than when they bought it after it was completed.

Unfortunately, due to a glut of equity financing in the market that is no longer the case. With how many films are being made every year, the likelihood of them being unable to find suitable content is slim. That’s why the only people still buying content require reputable directors and recognizable name talent.

Now as then, the only reason to pre-buy is so you can get the films you need when you need them. Given the glut of content filling the marketplace at the lower levels, the only films worth pre-buying have to be very high quality, with very high-quality assets.

In order to get a presale, you need 3 things:

The director must have a proven track record of 3+ films in a similar genre to the movie you’re producing now

some level of recognizable name talent,

The film must not be execution dependent.

All of this really boils down to distributors wanting to know that the movie they’re buying before it’s made will meet the needs of the outlets the distributor intends to release the film on.

That’s why the director’s track record is so important, and the notoriety of the cast is also a huge selling point. It’s also where the idea of execution dependence comes in. By Execution dependent, I mean that the film must not rely on the intricacies of good execution to be profitable. Something like Moonlight is very execution dependent, whereas The Expendibles 4 is not.

Pre-selling your film is also if the film is based on well-known existing source material. This could be a long-running series of books that might have flown under the radar of other movie producers, a recognizable web series, or even a video game. Uwe Boll made his career by pre-selling terrible movies based on video games. Of course, he also had the help of some very lenient German Tax incentives.

Letters of intent are much easier to get, as they’re a much less severe document. If you have a strong relationship with a filmmaker, it’s very possible you could get a letter of intent. It’s also possible that if you or your producer’s rep know what they’re doing, they can work with the right sales agents to escalate the document into a pre-sale once the package comes together.

Thank you very much for reading. As always, there’s a lot more to this than I could explain in a 600-word article. If you want to get more support in getting an LOI, you should go ahead and grab my free film business resource pack. It’s got a free e-book, lots of templates, money and time-saving resources, and even a monthly digest of content segmented by topic to help you continue to grow your career on a manageable schedule. Get it via the button below.

Check out more related content using the tags below.

The Two Main types of Financial Projections for an IndieFilm

If you’re seeking investment for your movie, you need to know how much it will make back. Here are the 2 primary ways to do that.

As a key part of writing a business plan for independent film, a filmmaker must figure out how much the film is likely to make back. This involves developing or obtaining revenue projections.

There are generally two ways to do this, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The first way is to do a comparative analysis. This means taking similar films from the last 5 years and plugging them into a comparative model to generate revenue estimates. The second way is to get a letter of intent from a sales agent and get them to estimate what they could sell this for in various territories across the globe.

This blog will compare and contrast these two methods (Both of which I do regularly for clients) in an effort to help you better understand which way you want to go when writing the business plan for your independent film.

Would you Rather Watch/Listen to this than read it? Here’s a corresponding video on my YouTube Channel!

Comparative Analysis - Overview

A comparative analysis is when you comb IMDb Pro and The-Numbers.com to come up with a set number of comparable films to yours. These are films that have a similar genre, similar budgets, similar assets, are based on similar intellectual property, and are generally within the last 5 years. If you can match story elements that are a plus, but there are only so many films with the necessary data to compare.

When I do it, I compare 20 films, average their ROIs from theatrical, pull numbers from home video wherever I can (Usually the-numbers.com), and then run them through a model I’ve developed to come up with revenue estimates. Honestly, I don’t do a lot of this work. Most of the time I refer it to my friends at Nash Info Services since they run The-Numbers.com and the brand behind these estimates means a lot to potential investors.

I will do it when a client asks though, generally as a part of a larger business plan/packaging service plan.

Sales Agency Estimates - Overview

Sales Agency Estimates are when you get a letter of intent from a sales agent, and as part of that deal the sales agent prepares estimates on what they think they can sell the film for on a territory-by-territory basis. Generally, they work from what buyers they know they have in these territories, whether or not they buy content like this, and what they normally pay for content like yours.

These estimates are heavily dependent on the state of your package, who’s directing your film, and who’s slated to star in it. If you don’t have much of a package and a first-time director, then you’re not going to get very promising numbers.

Comparative Analysis - Benefits

Generally, anyone can get these estimates. Some people figure out the formula and do it themselves, others pay someone like me or Bruce Nash to do it for them. There’s either a not insubstantial fee involved or a lot of time involved in getting them. They’ll generally satisfy an investor, especially if Bruce does it.

Sales Agency Estimates - Benefit

The biggest benefit to a sales agency approach is that if they’re doing estimates for you, they’re probably going to distribute your film. Also, these estimates have the potential to be more accurate, because they’re based on non-public numbers on what buyers are paying in current market conditions. Finally, if a sales agent has given you an LOI, these estimates are generally free.

Comparative Analysis - Drawbacks

The first drawback is likely that they’re either very time intensive or somewhat costly to produce. Also, because VOD Sales data is kept under lock and key, it’s very difficult to estimate total revenue from VOD using this method. Given how important VOD is, that’s a somewhat substantial drawback.

Further, these estimates are greatly helped by the name value of who made them. Likely, if the filmmaker makes them themselves, then they’re not as viable as if someone like Bruce or Me does them. This is not only because we both have a track record in them, (Bruce much Moreso) but also because we’re mostly impartial third parties.

These revenue estimates can be very flawed if a filmmaker makes them because many filmmakers have a tendency to only pick winners, not the films that lost money. In business, we call this painting too blue a sky, as it makes everything look sunny with no chance of rain. In film, there’s always a substantial chance of rain.

Sales Agency Estimates - Drawbacks

The biggest drawback to these estimates is that not everyone can get these estimates. You have to have a relationship with the sales agency for them to consider giving them to you. Generally, you’ll need to have convinced them to give you an LOI first. That’s not always the case though.

If you have a producer’s rep, they can sometimes get you through the relationship barrier, but they’ll often charge for doing so when we’re talking about a film that’s still in development.

Also, Sales agencies can sometimes inflate their numbers to keep filmmakers happy and convince them to sign. This does not look good to investors if that money never comes in

Conclusion

Overall, which method you use to estimate revenue depends entirely on what situation you find yourself in. If you have the ability to get the sales agency estimates, they can be VERY strong, if you don’t, the comparative estimates are reliable enough to do what you need them to do. That being said, I wouldn’t advise taking a comparative analysis to a sales agency.

Thanks for Reading! Creating revenue estimates is only part of raising money for your film. There’s a lot more you’ll need to know if you want to succeed. That’s a large part of why I created my indie film resource package, to help filmmakers get the knowledge and resources they need to grow their careers. It’s totally free and has things like a deck template, free e-book, and even specialized blog digests sent out on a monthly basis to help you understand how to answer the questions your investors will almost certainly have. Check it out at the button below.

Get more related content through the tags below.

5 Rules for Getting a Letter of Intent (LOI) From a Sales Agent for Your Film.

If you want someone else to finance your movie, you need to prove access to distribution. While a hard presale is best, it’s not always possible. Here’s a guide for getting a Letter of intent form a sales agent.

In order to properly package a movie, you need three things. Recognizable Name Talent, First Money in, and at least a letter of intent from a distributor. I’ve covered steps for preparing for calling agents in the Entrepreneurial Producer, (Free E-Book Here.) I’ve covered some of the ways you can get first money in this blog. So now, I’ll cover some rules for approaching sales agencies in the blog you’re about to read

The reason you need an LOI is that the cause of films not recouping their investor’s money is that they can’t secure profitable distribution. Your investors want to know you have a place to take the film once it’s done, so they can begin to get their money back. Before you start thinking that you’ll just try to start a bidding war after the film is done, you should be aware that generally doesn’t happen.

Before we begin, This Packaging concepts blog series was recommended by my friend Brittany, in the Producer Foundry group on facebook. I occasionally look to answer questions people have there, so if you want me to answer something join the group. Or, if you want definitely want to get some questions answered, you should join my Patreon. I’m very active in the comments.

1. This document isn’t a Pre-Sale.

It’s important to note that there’s a big difference between a Pre-Sale and a Letter of Intent. A Pre-Sale is something that you may well be able to take to the bank to take out a loan against. That is, if you’ve got a presale agreement from a reputable distributor or sales agency. If you’re working on making your first film, that’s probably not going to happen though.

To get a Pre-sale, you need to have a known director with a proven track record, a film that’s not Execution Dependent, and likely some noteworthy cast. Even then, the Pre-Sale often only covers the cast.

An LOI is a much less serious document. It’s essentially a letter guaranteeing that a sales agent will review the film on completion, and if it fits their business needs they will represent the film. Generally, the producer will give the sales agency an exclusive first look for the privilege of using their name to help package and finance the film. Sales Agencies can’t just give these to everyone, as it waters down their brand. You’ve got to compensate them in some way for taking a risk on you.

This is not the final document, you’ll negotiate a distribution agreement once the film is done. Don’t try to negotiate one at this point, since you’ll be in an inferior negotiation position.

2. Make sure there’s a time window on the sales agent’s first look

If you fail to put a time window on the sales agent's first look, you can lock yourself up and potentially lose the first window on the film. Generally, I’ll say something like 14 or 30 days from initial submission on completion of the film. This gives the sales agency time for review but doesn’t hurt the filmmaker’s options if they take too long. This also prevents them from tying you into a contract.

3. Only approach agencies that sell films like the one you want to make.

This may sound obvious, but if you’re looking for an LOI for a horror film, don’t approach sales agencies that deal primarily in family films. If all goes according to plan, this sales agency will be distributing your film when it’s done. You want to make sure they’re well-suited to sell your film when the time comes.

4. Look at the track record of the agency you want to work with

You need to look into what films the sales agent has made in the past, and how widely those films have been distributed. At this stage, doing this isn’t as important as when you negotiate the final distribution deal, but it is something you should know when going after a letter of intent.

Also, the track record of the sales agency or distributor has a direct impact on how valuable the LOI is. An LOI from Lionsgate means a lot more than an LOI from someone on the third floor at AFM this year. Looking at the track record can help you more accurately assess the value of the document you hold, so you can better present that information to potential investors.

5. Getting an LOI is Heavily Dependent on the Relationship with the Sales Agency.