How to Raise Development Funds for your Feature Film.

If you want to make a movie, you need to raise money. In order to raise any significant capital, you’ll need a package, and that cost money. Here’s where you raise the first money in.

Pretty much every filmmaker wants to find money to make their movie. Unfortunately, many don’t quite realize that in order to raise the kind of money you need to make anything above a micro-budget movie, you’ll generally need a lot already in place. It’s something of a catch-22. Investors need name talent to market the film, and distribution to make it available. Distributors need name talent and a tested team to give any meaningful commitments, and name taken need to know they’ll be paid. There are ways around all of this, but generally, they require money upfront. This blog is about how you raise it.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a magic bullet on any level of film funding. The best I can do is offer you tools and tactics to use to increase your chances of success. You will probably need more than one of these tools to get the job done.

Don't want to read? Check out the video on this topic below

Crowdfunding

Let’s get this one out of the way fast. Crowdfunding CAN be great for filmmakers not only as a way to raise partial funding, but also to engage yourself with your audience and provide market validation for both investors and distributors/sales agents. That said, it’s not without its drawbacks. Using crowdfunding as an early-stage race tool can cause your donors to question whether or not you’ll be able to get the whole film done. If you can’t, it can lead to problems. (Extra special shoutout to my patrons here, since we’re talking about crowdfunding.)

Friends and Family

I know, I know. This is the oldest piece of advice in the book. But, there’s a reason it’s still around. Your friends and family are (hopefully) among the people who are most likely to back and support you in this endeavor. If they’re like mine were when I was starting out, while they may be willing to help and actively want you to succeed, they’ll still need some proof it’s possible. However, the proof they’re like to need will probably be something easier to get than an investor would need. These

Equity

But Ben, didn’t you just say that you need more in place to get an investor? Yes and no. In order to raise a large round, you’ll need a lot in place, but if you’re only focusing on a smaller round you can get by with less. It is important to properly structure this investment though. You’ll either need to offer a more substantial stake in the company for the bigger risk taken for investing earlier, or you’ll need to do some other investment vehicle like Convertible debt.

Even at this stage, if you want to raise money from investors you’re going to need to create an independent film investment deck. You can learn more about it in this blog, or you can grab a template for free in my film business resource package in the button below.

Grants

Grants are great in that they don’t require you to pay back the money so long as you only use it for its intended purpose. They’re not so great in that they generally take a long time to be approved for the money, and you’re generally facing significant competition particularly for development stage grants.

Soft Costs and Deferrals

This essentially means calling in every favor you have to make sure that you have the best chance possible to succeed in developing a package for your film. This isn’t going to carry you the whole way though. Most people who do this for a living don’t work purely on a deferral or commission basis. I’m including myself in this, although I do defer a large portion of my fees and take on as much as I can on commission.

That said, while the higher-level connectors, Producers, Executive Producers, and the like are generally unwilling to work on a purely deferral or commission basis, the friends you need to make a great crowdfunding video, concept trailer, or something similar might not be. Getting their buy-in might help you make it to the next level.

Skin in the Game

Finally, we come down to the ever-present fallback of funding the development round yourself. This is generally the fasted way to complete the round, but it has the obvious drawback of needing deep enough pockets to just shell out and pay the money you need to get it done.

I know all of this is really hard to grasp, and quite frankly it’s a lot. While I do consult on this sort of stuff, I’m not cheap. (with good reason.) I try to make a lot of information available through my site, but there are times that you just kind of need someone to answer your questions and re-orient you. As such, I’ve decided to start a special mentorship group.

This special training group gets you access to additional content, an exclusive discussion group, and most importantly weekly group video calls where I’ll answer your questions personally, and occasionally bring on people who would also be of benefit to the group’s needs. Click the button below to go to a form and express interest in this group. Spots are limited.

Also, don’t forget about the Free indiefilm business resource package to get your free Investment deck template, e-book, white-paper, and more. .

Thanks so much for reading. Please share it! Also click the buttons below for more free content.

What Screenplays are Studios ACTUALLY Buying?

If you’re a screenwriter, you’ve probably toyed with the idea of selling your script. Here’s some advice from a script doctor and a rebuttal from an executive producer.

If you’re a screenwriter, you have two options. Produce it yourself, or option your work to a producer. In order to option your work, you need to understand who is going to buy your movie. Unfortunately, there’s more bad and incomplete information than there is good information out there. Recently, a client of mine forwarded an email he got back from a contact in Hollywood who worked as a script doctor. This email epitomized that bad information, so I thought I’d redact any contact information and publish it for others to learn from as well. (I did check with my client first, and he was good with it.)

Here’s what the script doctor said Hollywood wanted. Their responses in title, mine in the paragraphs following.

1. Contained Thriller or Horror: ideally one location about 5-8 actors (no A-listers needed). This is most scripts being bought or sold these days.

These are great if you’re producing the film yourself and looking to do it as cheaply as possible. Films like this can be shot on the cheap, so it's significantly easier to produce them. Given that horror or thriller movies are less execution or name-talent dependent they have a greater chance to sell on the strength of the genre alone. Given that, such producers are more interested in them. Unfortunately, these are the vast majority of the films made every year that find some degree of place in the market which has resulted in a massive glut in the market and each film makes next to nothing.

I know this because I've repped several of them. Most times the script doctors don’t actually know how the producers or production company end up getting paid, as the writers (and ESPECIALLY "Script Doctors”) are paid up-front

More than 20,000 films are made in the US every year, at most 10% of those get distribution to any meaningful degree. Thrillers and horror films are the only projects that have a chance at getting into that to 10% without IP or Talent, but in the end you still end up competing with 2,000 other films, most of which have better assets and positioning than you do. This is why I'm increasingly advocating other paths forward.

In general, the only way this is advantageous is if you produce it yourself. We're doing family films because that's what most every buyer wants right now, and there's an easier pipeline to follow that has a better chance of success if it gets done.

2. Something with an existing IP. A novel, a graphic novel/comic book, a short story, a short film... anything that already has a fan base or following ideally.

This is why I’m currently helping a client option the rights to some books, as it's the most reliable path to success even if its slightly longer path it is a better chance at success. If you want to get a film made first to make that part easier, it is a viable path. However, if you want to raise a larger amount of money so your film has a better chance at finding a bigger distributor and bigger audience, then you’ll need some level of recognizable IP. I heard Brett Ratner say in an interview at AFM several years back that if he was just starting out what he’d do is read voraciously and find the newest up-and-coming IPs. To option and use to build an audience. The alternative is to generate your own IP, but that in itself is a very long road fraught with danger, as this video from Lindsay Ellis illustrates very well.

RELATED VIDEO: HOW TO GET YOUR BOOK PUBLISHED IN 10 YEARS OR LESS!

Also: HA! He thinks expanded short films sell. That hasn't really been true for more than a decade since the amount of ready-to-sell feature films being made has ballooned, in fact, it's almost like features are the new shorts in terms of distribution revenue. But that's a topic for another day.

3. A specific character piece for an actor looking to stretch themselves. If you’ve got a character-driven piece and can get an A-list actor attached because it is something they haven’t done before, you’re good to go.

I heard this a lot in film school, but the real-world applications are limited. That is to say, while there is a kernel of truth in this concept, when it comes down to the implementation it's really more a platitude or truism at this point. There’s a strong case to be made that casting against type has its merit. The issue is that in general, the only way you can make it work is if you have a direct path to the name talent you want to talk to, and even then you have to get lucky and catch them at the right time. There are reasons I know this that I can’t publicly say…

4. Anything that will do well overseas. With China eating up all of our movies, they need scripts that are, fun, fast, action-packed and translate well and easily (aka not a lot of dialogue).

Again, something of a platitude or truism. Of course, you have to think about overseas, which is one big reason that comedies and dramas are complete no gos. The books below go into that in more detail than I can in a blog. (yes, there are affiliate fees, but it's only pennies and I picked the books custom for this blog.)

That’s the basics right now. Of course, the caveat is if you write a brilliant script, it doesn’t matter what genre it is, but in reality, your chances of having it made, sold, and even optioned are very difficult roads ahead.

And here's the crux of the disagreement with this script doctor. The brilliant script isn't so much as a way of breaking through any of the other things you need to be listed above, it's more a prerequisite to succeeding with any of them. We all hear stories of films making it through the studio system, but these are the exceptions, not the rules.

If selling your script doesn’t seem worth it, you’ll need to produce it yourself. You’ll probably need money to do that. If you want to raise money, you’ll need a myriad of documents, starting with an investment deck. My Free indiefilm resource pack has you covered with a template for that, as well as a free e-book, whitepaper, and a bunch of other templates too. Snag it for free in the button below. Thanks for reading, and if you liked it, please share it with someone who needs to know about selling their script.

Check the tags below for related content!

The 4 Stages of Indiefilm Finance (And Where to Find the Money)

Financing a film is hard. It might be easier if you break it up into more manageable raises. Here’s an outline on that process.

Most of the time filmmakers seek to raise their investment round in one go. A lot of people think that’s just how it’s done. As such, they ask would they try anything else. If you have a route into old film industry money you can go right ahead and raise money the old way. If you don’t, you might want to consider other options.

Just as filmmakers shouldn’t only look for equity when raising money, Filmmakers should consider the possibility of raising money in stages. Here are the 4 best stages I’ve seen, and some ideas on where you can get the money for each stage.

1. Development

If you want to raise any significant amount of money, you’re going to need a good package. But even the act of getting that package together requires some money. So one solution to getting your film made is to raise a small development round prior to raising a much larger Production round.

If you want to do this with any degree of success, you’re going to have to incentivize development round investors in some way. There are many ways you can do it, but they fall well beyond my word count restrictions for these sorts of blogs. If you’d like, you can use the link at the end of the blog to set up a strategy session so we can talk about your production, and what may or may not be appropriate.

Related: 7 Essential Elements of an IndieFilm Package

Most often, your development round will be largely friends and family, skin in the game, equity, or crowdfunding. Grants also work, but they’re HIGHLY competitive at this stage.

Books on Indiefilm Business Plans

2. Pre-Production/Production

It generally doesn’t make sense to raise solely for pre-production, so you should raise money for both pre-production and principal photography. This raise is generally far larger than the others, as it will be paying for about 70-80% of the total fundraising. It can sometimes be combined with your post-production raise, but in the event there’s a small shortfall you can do a later completion funding raise.

It’s very important to think about where you get the money for the film. You shouldn’t be looking solely at Equity for your Raise. For this round, you should be looking at Tax incentives, equity, Minor Grant funding if applicable, Soft Money, and PreSale Debt if you can get it.

Related: The 9 Ways to Finance an Independent Film

Post Production/Completion

Some say that post-production is where the film goes to die. If you don’t plan on an ancillary raise, then too often those people are right. Generally you’ll need to make sure you have around 20-25% of your total budget for post. It’s better if you can raise this round concurrently with your round for Pre-Production and Principle Photography

The best places to find completion money are grants, equity, backed debt, and gap debt

4. Distribution Funding/P&A

It’s very surprising to me how difficult it is to raise for this round, as it’s very much the least risky round for an investor, since the film is already done.

Theres a strong chance your distributor will cover most of this, but in the event that they don’t, you’ll need to allocate money for it. Generally, I say that if you’re raising the funds for distribution yourself, you should plan on at least 10% of the total budget of the film being used for distribution.

Generally you’ll find money for this in the following places. Grants, equity, backed debt, and gap debt.

If you like this article but still have questions, you should consider joining my email list. You’ll get a free e-book, monthly digests of articles just like this, segmented by topic, as well as some great discounts, special offers, and a whole section of my site with FREE Filmmaking resources ONLY open to people on my email list. Check it out!

The 7 Essential Elements of A Strong Indie Film Package

If you want to get your film financed by someone else, you need a package. What is that? Read this to find out.

Most filmmakers want to know more about how to raise money for their projects. It’s a complicated question with lots of moving parts. However, one crucial component to building a project that you can get financed is building a cohesive package that will help get the film financed. So with that in mind, here are the 7 essential elements of a good film package.

1.Director

As we all know, the director is the driving force behind the film. As such, a good director that can carry the film through to completion is an essential element to a good film package. Depending on the budget range, you may need a director with an established track record in feature films. If you don’t have this, then you probably can’t get money from presales, although this may be less of a hard and fast rule than I once thought it was.

Related:What's the Difference between an LOI and a Presale?

Even if you have a first-time director, you’ll need to find some way of proving to potential investors that they’ll be able to get the job done, and helm the film so that it comes in on time and on budget

2. Name Talent

I know that some filmmakers don’t think that recognizable name talent adds anything to a feature film. While from a creative perspective, there may be some truth to that, packaging and finance is all about business. From a marketing and distribution perspective, films with recognizable names will take you much further than films without them. I’ve covered this in more detail in another blog, linked below.

Related: Why your Film Needs Name Talent

Recognizable name talent generally won’t come for free. You may need a pay-or-play agreement, which is where item 7 on this list comes in handy.

3. An Executive Producer

If you’re raising money, you should consider engaging an experienced executive producer. They’ll be able to help connect you to money, and some of them will help you develop your business plan so that you’re ready to take on the money when it comes time to. A good executive producer will also be able to greatly assist in the packaging process, and help you generate a financial mix.

Related: The 9 Ways to finance an Independent Film.

I do a lot of this sort of work for my clients. If you’ve got an early-stage project you’d like to talk about getting some help with building your package and/or your business plan I’d be happy to help you to do so. Just click the clarity link below to set up a free strategy session, or the image on the right to submit your project.

4. Sales Agent/Distributor

If you want to get your investors their money back, then you’re going to need to make sure that you have someone to help you distribute your independent film. The best way to prove access to distribution is to get a Letter of Intent from a sales agent. The blog below can help you do that.

Related: 5 Rules for Getting an LOI From a Sales Agent

5. Deck/Business Plan

If you’re going to seek investors unfamiliar with the film industry, you’re going to need a document illustrating how they get their money back This can be done with either a 12-slide deck, or a 20-page business plan. I’ve linked to some of my favorite books on business planning for films below.

6. Pro-Forma Financial Statements

Pro forma financial statements are essentially documents like your cash flow statement, breakeven analysis, top sheet budget, Capitalization Table, and Revenue Distribution charts that help you include in the latter half of the financial section of a business plan.

There’s a lot more information on these in the book Filmmakers and Financing by Louise Levinson. I’m also considering writing a blog series about writing a business plan for independent film. If you’d like to see that, comment it below.

7. Some Money already in place

Yes, I know I said that you need a package to raise money, but often in order to have a package you need to have some percentage of the budget already locked in. Generally, 10% is enough to attach a known director and known talent. If you’re looking for a larger Sales Agent then you’ll also need to have some level of cash in hand.

This is essentially a development round raise. For more information on the development round raises, check out this blog!

Thanks for reading, for more content like this in a monthly digest, as well as a FREE Film Market Resources Package, check out the link below and join my mailing list.

Check the tags below for related content.

Why You Still Need Name Talent in Your IndieFilm

If you don’t think having recognizable names in your film will help you grow your career, you’re wrong. Here’s why.

In the age of easily accessible self-distribution, cheap gear, and the ability to make and distribute a feature film for less than 10,000 dollars it’s understandable to wonder why you would want to spend 10,000-100,000 dollars a day on recognizable name talent. Many proclaim that hiring recognizable name talent is simply a waste of time and money.

Speaking as someone who makes most of their living from film distribution, these people are wrong. Here are 5 reasons why.

Recognizable Name Talent Significantly increases the Profile of the Film

In an age where anyone can make a film, the challenge becomes less one of making a film, and more one of rising above the white noise created by others also making films. Recognizable name talent can be a great help you set yourself apart. The notoriety brought by recognizable name talent helps raise public awareness of your project and greatly increases interest from high profiles sales agents and distributors. Also, if they have a large social media presence and agree to help promote your film, it will have a tangible impact on the profile of your film.

Recognizable Name Talent Significantly increases the chance of meaningful press coverage.

With the higher profile that names talent brings to your project. Press coverage will compound the impact on the awareness of your film that name talent brings. If your film gets enough coverage, then a lot of the marketing will be done for you, and you’ll be able to attract the pieces of the puzzle that you’d otherwise need to chase. These puzzle pieces can be anything from additional tickets sold, to in-kind product placement, and potentially even completion funding once your film is in the can.

Several of my pre-completion press articles have been due in large part to having recognizable names attached to the project.

Recognizable Name Talent Increases the likelihood of getting into festivals

I know this isn’t going to be a popular thing to say, but film festivals don’t solely look at the quality of a film in deciding which ones should be programmed. They also consider the fit with the festival’s brand, the current political climate, as well as the profile of the film and what showcasing the film, would bring to the festival.

Given that the profile of the film is greatly raised by recognizable name talent, it’s something that festival programmers will consider when deciding whether or not to program your film

Name Talent Increase Your Distribution Options

From my personal experience in distribution and sales, it is easier to sell a mediocre film with names than a great film without them. This is true regardless of genre, although certain genres absolutely necessitate recognizable names if you want any international distribution.

Recognizable Name Talent is a great way to make both sales agents and distributors stand up and take notice. Getting a star in your film has a direct and tangible impact on your chances of getting a profitable distribution deal.

Without recognizable name talent, it’s almost impossible to get a minimum guarantee. Further, many of your international sales will be revenue share only. With Name Talent, it’s far more likely that you’ll get a minimum guarantee from the sales agent, and the deals with international buyers will be license fees or MGs instead of revenue share deals.

Name Talent Increases Self-Distribution Sales

Finally, even if you plan on self-distributing your film, recognizable name talent will help you move units. Raising the profile of your film by having a star in your film will help you place higher in Amazon and iTunes search results, which will have a tangible impact on your bottom line.

Thanks so much for reading. If you enjoy my blog and want more, you should sign up for my FREE independent film business resources package. It’s got an e-book with a lot of articles like this one you can’t find elsewhere, as well as templates to help you grow your film career. One of the articles in the e-book includes a script for calling actors’ agents. Click the button below for more information.

5 Rules for Vetting Your Producer’s Rep

We producer’s reps are generally known to be slimy used car salespeople. It’s not always the case, but there’s a reason the stereotype exists. Heres’ how to vet your rep, (include me on these too)

The term producer’s rep has been given a bad name. A lot of people think that Producer’s reps are just money-grubbing middlemen (or middlewomen, or middlethems) who don’t add any value to your project. As a producer’s rep myself, I’d like to take issue with the narrative that producer’s reps are slimy con artists who will overcharge you without adding value. Unfortunately, I can’t. For the most part, the rumors exist for a reason.

So with that in mind, here are 5 ways to vet your producer’s rep. If you want to sign up with me, do the same.

Ask what their upfront fees are.

If you’re simply looking for a rep to broker your completed film, then the upfront fees should be very low, or nonexistent then they’ll take a piece of the pie for the length of the deal. There are producer’s representatives who operate on a service basis, I.E. they’ll be paid a few thousand dollars with half up front, half on success. In theory, you end up paying less this way, but the incentives are not always in line with the filmmaker’s best interest.

I’ve heard stories of other reps charging 5000 dollars to represent a film to various sales agencies. If the Rep got you a deal, the rep would then retain 35% of all money from that deal. This is without even negotiating for a better deal with the sales agency, essentially just making a few calls and writing a few emails.

Not all service deals are bad, but you have to do extra diligence if that’s how your rep operates.

Also, it should be noted that if you want your rep to do anything other than basic brokering, you should expect to pay them. When I work with filmmakers at an early stage to guide investment decks, help attach talent, write business plans, or any other consulting-oriented services, you should expect to pay some not-insignificant fees. Nobody on a film shoot should be asked to work for free, including us. We still have bills, and it took a lot of investment for us to develop our skills and contacts.

Related: What Does a Producer's Rep DO Anyway?

For straight representation/brokerage services, I charge nothing upfront, and as of this writing, I don’t even charge recoupable expenses. I charge 10% for connection to sales agents, and 18% if I sell directly to buyers. (Generally only domestically.) I also negotiate with sales agencies and buyers to get you/us the best possible deal.

That being said, brokerage tasks for completed films are the only thing I don’t charge upfront for. For other tasks, I either charge by the hour or by the job, sometimes with performance bonuses or deferments.

2. Ask them if they watched your movie.

If they’re offering to represent your movie, they had better have watched it. If they try to say that they don’t remember the film because they watched 8 last week, they’re probably lying. I watch 5-8 a week. If I’m making an offer I’ve probably watched it all. If I don’t think I can sell it, I stop after 20 minutes.

Most sales agents and Producer's Reps have a similar system. If they can't say some specifics about your film, they're probably lying about watching it.

3. Look them up on imdb.

You want someone who’s not all talk. You want to see some associate, co-, and executive producing credits on their IMDb. I generally ask to be credited as an executive producer because it’s the most accurate credit for the job I do.

If you want to check out what I’ve done, here’s my imdb,

4. Ask them who they have direct relationships with

Any good rep will have existing relationships with some sales agencies. That’s why you would want to hire them in the first place. Great reps will have direct relationships with buyers. If they can’t list out a few sales agencies that they’ve worked with in the past off the top of their head, then they’re probably not going to do their job very well.

While I won’t list the ones I’ve worked with here, I will tell you if you ask me when on a call or after you submit your film below.

5. Call 3 of their previous clients

This is true for both Producer’s Reps and Sales Agencies. You’ve GOT to call the clients of your rep and ask for a reference. If you ask for references and your rep gets upset, then it’s likely a sign you shouldn’t use their services. Honestly, It’s better if you just look up those filmmakers on IMDb and call them yourself. You can find all the necessary info on imdbPro.

Thanks so much for reading! If you’re looking for a producer’s rep, you should check out my services page. If you’re not quite there yet, but want to more know about the film biz, you should join my mailing list and get my FREE Film market resource package. Links below in the buttons.

Check the Tags for more indie film biz content.

5 Rules for Getting a Letter of Intent (LOI) From a Sales Agent for Your Film.

If you want someone else to finance your movie, you need to prove access to distribution. While a hard presale is best, it’s not always possible. Here’s a guide for getting a Letter of intent form a sales agent.

In order to properly package a movie, you need three things. Recognizable Name Talent, First Money in, and at least a letter of intent from a distributor. I’ve covered steps for preparing for calling agents in the Entrepreneurial Producer, (Free E-Book Here.) I’ve covered some of the ways you can get first money in this blog. So now, I’ll cover some rules for approaching sales agencies in the blog you’re about to read

The reason you need an LOI is that the cause of films not recouping their investor’s money is that they can’t secure profitable distribution. Your investors want to know you have a place to take the film once it’s done, so they can begin to get their money back. Before you start thinking that you’ll just try to start a bidding war after the film is done, you should be aware that generally doesn’t happen.

Before we begin, This Packaging concepts blog series was recommended by my friend Brittany, in the Producer Foundry group on facebook. I occasionally look to answer questions people have there, so if you want me to answer something join the group. Or, if you want definitely want to get some questions answered, you should join my Patreon. I’m very active in the comments.

1. This document isn’t a Pre-Sale.

It’s important to note that there’s a big difference between a Pre-Sale and a Letter of Intent. A Pre-Sale is something that you may well be able to take to the bank to take out a loan against. That is, if you’ve got a presale agreement from a reputable distributor or sales agency. If you’re working on making your first film, that’s probably not going to happen though.

To get a Pre-sale, you need to have a known director with a proven track record, a film that’s not Execution Dependent, and likely some noteworthy cast. Even then, the Pre-Sale often only covers the cast.

An LOI is a much less serious document. It’s essentially a letter guaranteeing that a sales agent will review the film on completion, and if it fits their business needs they will represent the film. Generally, the producer will give the sales agency an exclusive first look for the privilege of using their name to help package and finance the film. Sales Agencies can’t just give these to everyone, as it waters down their brand. You’ve got to compensate them in some way for taking a risk on you.

This is not the final document, you’ll negotiate a distribution agreement once the film is done. Don’t try to negotiate one at this point, since you’ll be in an inferior negotiation position.

2. Make sure there’s a time window on the sales agent’s first look

If you fail to put a time window on the sales agent's first look, you can lock yourself up and potentially lose the first window on the film. Generally, I’ll say something like 14 or 30 days from initial submission on completion of the film. This gives the sales agency time for review but doesn’t hurt the filmmaker’s options if they take too long. This also prevents them from tying you into a contract.

3. Only approach agencies that sell films like the one you want to make.

This may sound obvious, but if you’re looking for an LOI for a horror film, don’t approach sales agencies that deal primarily in family films. If all goes according to plan, this sales agency will be distributing your film when it’s done. You want to make sure they’re well-suited to sell your film when the time comes.

4. Look at the track record of the agency you want to work with

You need to look into what films the sales agent has made in the past, and how widely those films have been distributed. At this stage, doing this isn’t as important as when you negotiate the final distribution deal, but it is something you should know when going after a letter of intent.

Also, the track record of the sales agency or distributor has a direct impact on how valuable the LOI is. An LOI from Lionsgate means a lot more than an LOI from someone on the third floor at AFM this year. Looking at the track record can help you more accurately assess the value of the document you hold, so you can better present that information to potential investors.

5. Getting an LOI is Heavily Dependent on the Relationship with the Sales Agency.

If you walk in cold and start asking for an LOI on the first meeting, you’re not likely to be successful. It takes time and a fair amount of correspondence to get to the point where a sales agency is willing to take a risk on you.

If you don’t want to spend the time and money to establish these relationships by going to markets and having calls and emails with the sales agency, you may want to consider a Producer’s Rep.

Most producer’s rep will require some level of upfront payment for this sort of work. I charge a relatively small amount upfront and a larger amount on success for this sort of work. That said, I’m relatively selective about what I take on. If you’d like to find out more click the links below to submit your project, or book a call with me on Clarity to pick my brain about the next steps. Alternatively, you can sign up for a free strategy session and talk about what the best next steps for you would be. I also offer educational programs that will teach you how to get these for yourself. Those start with a one-hour strategy session. In this one-hour strategy session, I'll help you figure out where you are, what the next steps for you are, and what the best course of action for helping you get there would be.

Thanks so much for reading! This is only a primer, and in order to succeed you’ll need a lot more information on the business of indie film. If you want help getting that, you should check out Guerrilla Rep Media’s independent film business resource package. You’ll get a free-ebook, lots of templates, money-saving resources, and even a monthly content digest delivered to your inbox to help you grow your indie film company and premier. It’s completely free and linked in the button below.

Check the tags below for more related content.

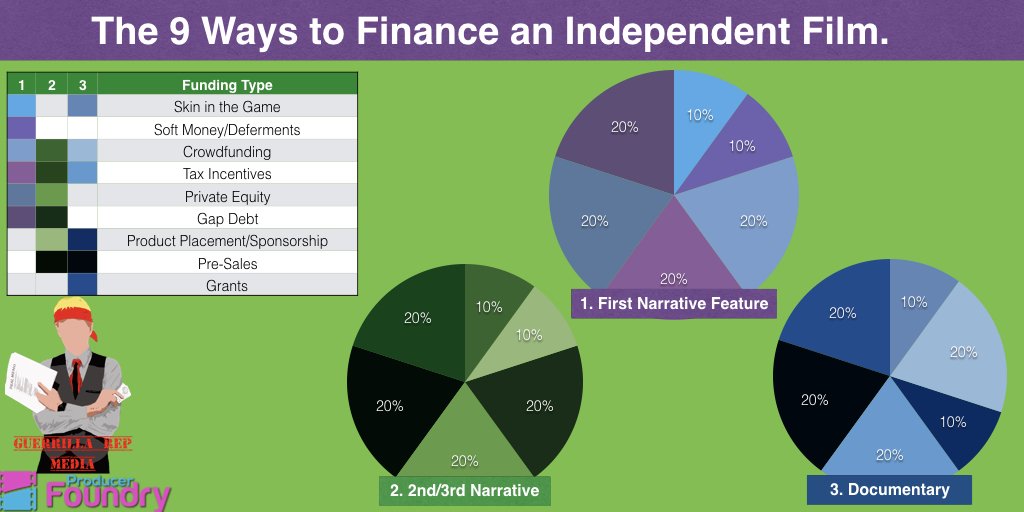

The 9 Ways to Finance an Indiependent Film

There’s more than one way to finance an independent film. It’s not all about finding investors. Here’s a breakdown of alternative indie film funding sources.

A lot of Filmmakers are only concerned with finding investors for their projects. While films require money to be made well, there’s are better ways to find that money than convincing a rich person to part with a few hundred thousand dollars. Even if you are able to get an angel investor (or a few ) on board, it’s often not in your best interest to raise your budget solely from private equity, as the more you raise the less likely it is you’ll ever see money from the back end of your project.

Would you Rather Watch or Listen than Read? I made a video on this topic for my YouTube Channel.

So here’s a very top-level guide to how you may want to structure your financial mix. The mixes in the image above loosely correspond to the financial mix of a first-time film, a tested filmmaker’s film, and a documentary. They’re also loose guidelines, and by no means apply to every situation, and should not be considered financial or legal advice under any circumstance. This is just the general experience of one Executive producer.

Piece 1 — Skin in the game. 10–20%

Investors want you to be risking something other than your time. The theory is that it makes you more likely to be responsible with their money if you put some of yours at risk. This can be from friends and family, but they prefer it come directly from your pocket.

I've gotten a lot of flack for this. However, the fact investors want skin in the game is true for any industry or any business. Tech companies normally have skin in the game from the founders as well, not just time, code, or intellectual property.

However, if you’ve got a mountain of student debt and no rich relatives, then there is another way…

Piece 2 — Crowdfunding 10–20%

I know filmmakers don’t like hearing that they’ll need to crowdfund. I understand it’s not an easy thing to do. I’ve raised some money on Kickstarter and can verify that It’s a full-time job during the campaign if you want to do it successfully. However, if you can hit your goal, not only will you be able to put some skin in the game, and retain more creative control and more of the back end but you’ll also provide verifiable proof that there’s a market for you and your work. Investors look very kindly on this.

That said, just as success provides strong market validation as a proof of concept, failing to raise your funding can also be seen as a failure of concept. and make it more difficult to raise than it would otherwise have been. Make sure you only bite off what you can chew.

Due to the difficulty in finding money for an independent film, the skin in the game or crowdfunding portion of the raise for a director’s first project is often a much higher percentage of the raise than it will be for their future projects.

Piece 3 — Equity 20–40%

Next up is equity. This is when an investor gives you money in return for an ownership stake in the company. From a filmmaker's perspective, it’s good in that if everything goes tits up, you don’t owe the investors their money back. Don't misunderstand what I mean by this. You ABSOLUTELY have a fiduciary responsibility to do your due diligence and act in the best interest of your investors to do absolutely everything in your power to make it so they recoup their investment. If you do that, or if you commit fraud, your investors can and likely will sue the pants off of you. You’ll have an uphill battle on that as well since they probably have more money for legal fees than you do.

Also, you will need a lawyer to help you draft a PPM. You shouldn't raise any kind of money on this list without a lawyer, with the possible exception of donation-based crowdfunding or grants. In general, just remember that I’m a dude who produced a bunch of movies who writes blogs and makes videos on the internet. Not a lawyer or financial advisor. #Notlegaladvice #Notfinancialdvice #mylawyermakesmewritethesesnippets.

It’s bad in that if everything goes extremely well, they get a huge percentage of your film. So it deserves a place in your financial mix, but ideally a small one.

For a longer list of my feelings on this topic, check out Why film needs Venture Capital, or One Simple Tool to Reopen Conversations with Investors

Piece 4 — Product Placement 10–20%

Product placement is when you get a brand to compensate you for including their product in your film. It’s more common in the form of donations or loans for use than hard money, but both can happen with talent and assured distribution. If you’re a first-timer, it’s difficult to get anything other than donated or loaned products.

Piece 5 — Presale Backed Debt 0–20%

Everything you read tells you the presale market has dried up. To a certain degree, that is true. However, it’s more convoluted than you may think. According to Jonathan Wolfe of the American Film Market, the presale market has a tendency to ebb and flow with the rise and fall of private equity in the filmmaking marketplace. There’s been a glut of equity for the past several years that’s quickly drying up.

That said, there are a lot of other factors that will determine where pre-sales end up in a few years. The form has shifted, in that it’s generally reputable sales agents that give the letters instead of buyers and territorial distributors. You then take that letter to a bank where you can borrow against it at a relatively low rate.

Piece 6 — Tax incentives 10%-20%

While many states have cut their filmmaking tax incentives, it’s still a very viable way to cover some of the costs of making your project. It is worth noting that the tax incentive money is generally given as a letter of credit, which you can then borrow against or sell to a brokerage agency. It’s not just a check from the state or country you’re shooting in. This system of finance is significantly more viable in Europe than it is in the US, but no matter where you plan on shooting it needs to be part of your financial mix.

Piece 7 — Grants 0–20%

There are still filmmaking grants that can help you to make your project. However, that’s not something that is available to all filmmakers, especially when they’re first making their projects. Don’t think grants don’t exist for you and your project, because they probably do, spend an afternoon googling it. My friend Joanne Butcher of www.FilmmakerSuccess.com suggests applying for one grand a month for the indefinite future, as when you do so you’ll develop relationships with the foundations you contact which can be invaluable for your career growth.

Grants are much easier to get as a completion fund once you’ve shot your film. Additionally, films made overseas are more likely to be funded by grants than those shot here in the US.

Piece 8 — Gap/Unsecured Debt 10–40%

Gap debt is an unsecured loan used to create a film or television series. This means that the loan has no collateral, be it product placement, Presale, or tax incentive. It used to be handled by entertainment banks for a very high interest rate, I can’t say who my source was on this, but I have heard of interest rates in excess of 50% APR. That market has been largely taken over by private investors loaning money through slated, which did bring interest rates down. Unsecured debt almost certainly requires a completion bond, which generally means that it’s only suitable for projects over 1mm USD in budget.

In general, you should use this form of financing as little as possible, and pay it back as quickly as possible. Again, Not legal or financial advice.

Piece 9 — Soft money and Deferments — whatever you can

Soft money is funding that isn’t given as cash. This can be your crew taking deferred payment for their services, or receiving donated or loaned products, locations, and anything else meant to get your film made. This isn’t so much funding as cost-cutting. It often includes donations or loans from product placement.

If you like this content and want to learn more about film financing, you should consider signing up for my mailing list. Not only will you a free e-book, but you’ll also get a free deck template, contract tracking templates, and form letters. Plus you’ll stay in the know about content, services, and releases from Guerrilla Rep Media.

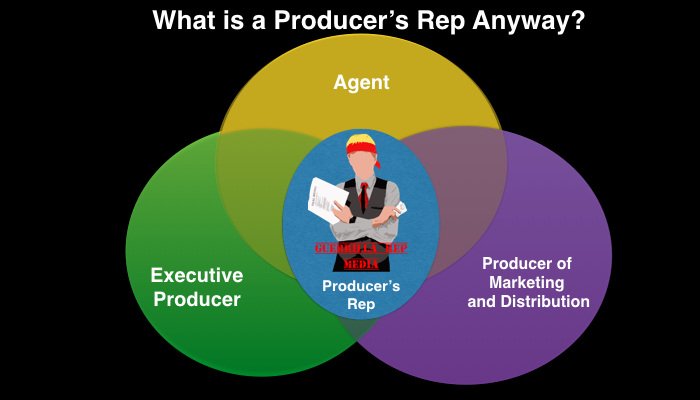

What does a Producer’s Rep Do Anyway?

Outside of the film industry, few people understand what a producer does. Inside of the indusrt, the jargon gets even deeper. This article examines the difference between Agents, Executive Producers, Producer’s of Marketing and Distribution, and Producer’s reps, as well as their roles and responsibilities.

As stated in the article What's the difference between a sales agent and a distributor, one of the most common questions I get is What does a producer’s Rep Do? Since that post teaches the major distribution players are by type, (you should read it first.) I will now thoroughly answer what a producer’s rep does.

Simply put, a Producer’s rep is a mix between a PMD and an executive producer. A Producer’s Rep takes on a lot of the business development jobs for a film. We wear a lot of hats. Most often we'll connect filmmakers with completed projects to sales agents and negotiate the best possible deal. We're skilled negotiators with a deep knowledge of the film distribution scene, and entrenched connections there.

Would you rather watch or listed to a video instead of reading an article? Check out this video on my youtube channel for most of the same information.

If a producer's rep comes on in the beginning, we’ll do the job of an executive producer. We'll help you finance the film in the best way possible. not just through equity investment, but planning proper utilization of tax incentives, pre-sales, crowdfunding, occasional product placement, and sometimes helping to connect you to some of our angel contacts. That said, if we’ve never met, you have no track record and want us to start raising money for you, that probably won’t happen.

Not all producer’s reps will work with first-time directors and producers, I will, but generally only on completion or near the end of post-production. I will not help someone who I have not worked with before garner investment for their projects, except in very limited circumstances. I will help filmmakers get their financial mix in order. If a rep makes connections for investment, we need to know if the filmmakers I'm working with can deliver a quality product and get our investment contacts their money back.

A Good Producer’s Rep will also be able to act as a PMD, or at least refer you to a good one. We don't just work in traditional distribution, but we can help plan and implement other tactics including proper use of VOD. We’ll help you plan your marketing and distribution, then we’ll tell you how to implement it, helping you along the way. We’ll help you develop the best package in order to mitigate the risk taken by our investors. If we do bring on investors, you’d best believe we’re with you through the end of the project, to make sure that everyone ends up better off. We’ll check in and act as a coach to help you grow to the next level.

In a lot of ways, we’re agents for producers and films. Good reps, like good agents, won’t just think about this project, they’ll help you use your projects to move to the next step in your career.

So how do you pay a Producer’s Rep? Since the services we offer are so varied, our pay scale is as well. Some things are based primarily on commission. Sometimes that commission will come with a small[ish] non-refundable deposit that would be things like connecting to distribution. That commission is generally around 10%, but can range between 5-15%. Some things [like document and plan creation] are a flat fee, others are hourly plus commission on completion. That would apply primarily to packaging.

It is worth noting that not all producers reps are trustworthy. There are some that charge 5 figures upfront with no guarantee of performance. Admittedly, no one can guarantee they can sell your film, or get it financed investment. If they guarantee it and ask for a large upfront payment, you should be very wary of them. However, there are some with a strong track record of doing so. Just as you would when talking with sales agents, talk to people who have worked with them in the past.

Most reps will give you a discount based on doing multiple services. Remember to check last week's post for an idea of what each major player in indiefilm distribution Does!

If reading this made you think you want a producer’s rep, check out the Guerrilla Rep Media Services section!

If you like this content but aren’t ready to look into hiring us, but would like educational content you should for my Resources list to receive monthly blog digests segmented by topic. Additionally, you’ll get a FREE E-book of The Entrepreneurial Producer, plus a heaping helping of templates and money-saving resources to make your job finding money or the right distribution partner significantly easier.

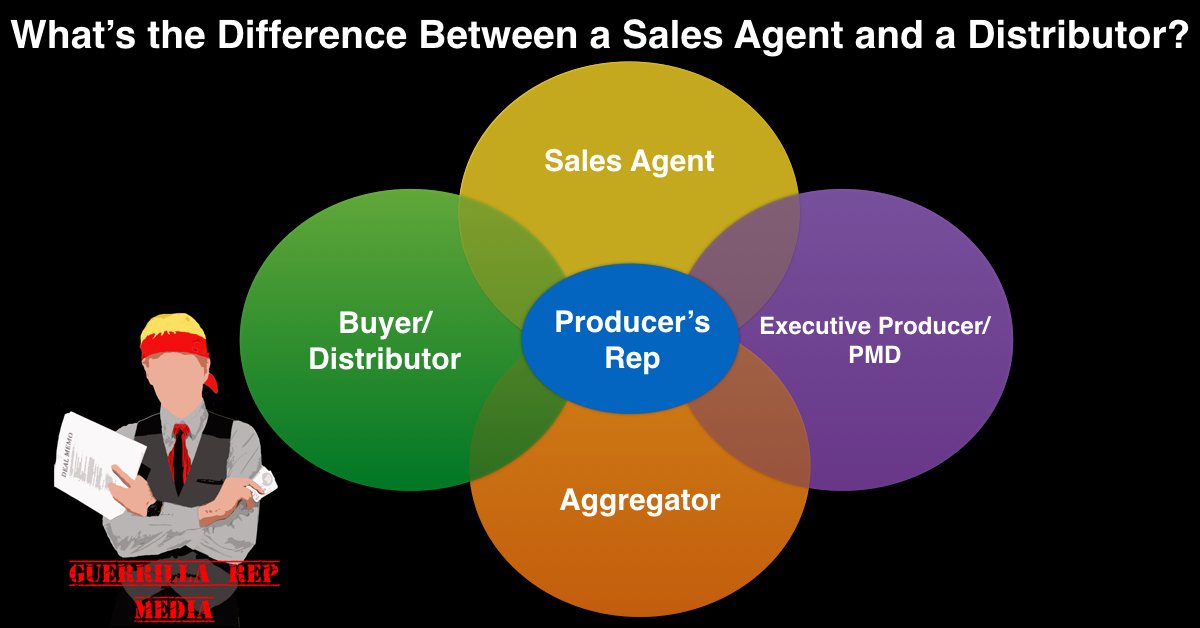

What’s the Difference between a Sales Agent and Distributor?

Too few filmmakers understand distribution. Even something as basic as the disfference between each industry stakeholder is often lost in translation. This blog is a great place to start

As a Producer’s Rep, one of the questions I get asked the most is what exactly do I do? The term is somewhat ubiquitous and often mean different things to different people. So I thought it might be a good idea to settle the matter. In this post, I’ll outline what a producer’s rep is, and how we interact with sales agents, investors, filmmakers, and direct distribution channels. But first, we need a little background on some of the terms we’ll be using, and what they mean. These terms vary a bit depending on who you ask, but this is what I’ve been able to gather.

Would you rather watch/listen than read? Here’s a video on the same subject from my Youtube Channel.

Like and Subscribe! ;)

DISTRIBUTOR / BUYER

A distributor is someone who takes the product to an end user. This can be anything a buyer for a theater chain, a PayTV channel, a VOD platform, to an entertainment media buyer for a large retail chain like Wal-Mart, Target, or Best Buy. The rights Distributors take are generally broken up both by media type and by territory.

For Instance, if you were to sell a film to someone like Starz, they would likely take at least the US PayTV and SVOD rights, so that it could stream on premium television and their own app which appears on other SVOD services like Amazon Prime, or Hulu. They make take additional territories as well.

Conversely, it’s not uncommon to sell all of France or Germany in one go. It should are often sold by the language, so sometimes French Canada will sell with France. This is less common as of late.

Generally, these entities will pay real money via a wire transfer, and almost deal directly only with a sales agent. Although sometimes to a producer’s rep, and VOD platforms will generally deal with an aggregator. The traditional model of film finance is built around presales to these sorts of entities, but that presale model has recently shifted.

Recently, more sales agents have begun distributing in their territory of origin. XYZ is a good example of this. Some distributors have branched out into international sales. This is something that we did while I was at the Helm of Mutiny Pictures, to allow us to deal with filmmakers directly in a more comprehensive way.

Sales Agents

A Sales agent is a person or company with deep connections in the world of international sales. They specialize in segmenting and selling rights to individual territories. Often, they will be distributors themselves within their country of origin. This business is entirely relationship based, and the sales agents who have been around a while have very long-term business relationships with buyers all around the world. That’s why they travel to all of the major film markets.

Examples on the medium-large end would be Magnolia Pictures international, Tri-Coast Entertainment, and Multivissionaire. WonderPhil is up and coming as well, as is OneTwoThree Media. Lionsgate and Focus Features would also be considered distributors/sales agents, but they’re very hard to approach. They also both focus on Distribution over sales.

Generally, these sales specialists will work on commission. They may offer a minimum guarantee when you sign the film but that is not common unless you have names in your movie. Generally, they will charge recoupable expenses which mean you won’t see any money until after they’re recouped a certain amount. In general, these expenses will range between 10k and 30k, with the bulk falling between 20 and 25k. If it’s higher than 30k without a substantial screen guarantee, you should probably find another sales agent. There are ways around this, but I’ll have to touch on this in a later blog [or book].

A sales agent commission will be between 20% and 35%, this is variable depending on several factors, but generally 25% or under is generally good, and over 30% is a sign you should read more into this sales agent. Lately, this has been trending towards 20% with a slight uptick in expenses.

Aggregators

Aggregators are companies that help you get on VOD platforms. The most important service they provide is helping you conform to technical specifications required by various VOD platforms. This job is not as easy as you would think it is, which is why they charge so much. Additionally, they have better access to some VOD platforms than others. These days, it’s very difficult to get on iTunes or most platforms other than Amazon’s Transactional section without one.

Generally, aggregators charge a not insubstantial fee to get you on these platforms, and they offer little to help you market the project. Companies like this include Bitmax and arguably filmhub or IndieRights.

There are merits to going this this route, but they can be expensive, often costing about one thousand USD upfront and growing from there. If they operate on a commission like Filmhub or Indierights, they won’t help you with marketing so you’ll have to spend a decent amount there in order to get your film seen.

Producer of Marketing & Distribution (PMD)

In the words of Former ICM agent Jim Jeramanok, PMDs are worth their weight in gold. A PMD is a producer who helps you develop your marketing and social media strategy, your Festival strategy, and your distribution strategy. They’re also quite likely to have some connections in distribution. They’re there to give your film the best possible chance at making money when it’s done.

Generally, they’re paid just as any other producer would be, but if they’re good, they’re worth every penny. With a good PMD on board, your project’s chances for monetary success are exponentially better.

If you’re an investor reading this, you want any film you invest in to at least have access to a PMD or Producer’s Rep, if not a preferred sales agent or at least domestic distribution. (Not Financial Advice)

Executive Producer (EP)

In the independent film world, these are producers who are hyper-focused on the business of independent film. They either help raise money to make the film, or they help bring money back to those who put money into it in the first place. As such, the traditional definition in of an indiefilm executive producer is someone who helps you package projects by attaching, bankable talent, investors, or other forms of financing. They’ll also help you design a beneficial financial mix, [I.E. where can you best utilize tax incentives, presales, brand integration, and equity, and gap debt.] in order to help your project have the best chance of success. They can also play a significant role in distribution. The latter is where most of my EP credits come from.

Often, they’ll take a percentage of what they raise or what they bring in. sometimes they’ll require a retainer, but most of the time they should have some degree of deliverables such as business plans, decks, or similar as part of that. These fees should not be huge, but they will be enough to give you pause due to the amount of specialized work involved in doing these jobs.

Producer’s Reps

I’ll go into this much more deeply next week, But Producer’s Reps are essentially a connector between all of these sorts of people and companies. Producer’s Reps will connect you do sales agents, aggregators, buyers, and investors. But more than that, a good one will help you figure out how and when to contact each one. Most often, they’re credited as an executive producer or a consulting producer as the PGA does not have a separate title that applies to this particular skillset. For a more detailed analysis of what exactly a Producer's Rep does, Check out THIS BLOG!

Thank you so much for reading! If you found it useful, please share it to your social media or with your friends IRL. If you want more content like this in your inbox segmented by month, you should sign up for my resources pack. I send out blog digests covering the categories and tags on this site once per month. You’ll also get a free EBook of The entrepreneurial producer with this blog and 20 other articles in it, as well as templates, form letters, and money-saving resources for busy producers.

If this all seems like a lot, and you need your own personal docent to guide you through the process, check out the Guerrilla Rep Media Services page. If you’d rather just get a map or an audio tour and explore the industry on your own, the products page might have some useful books or courses for you. Finally, if you just appreciate the content and want to support it, check out my Patreon and substack.

Peruse the tags below for related free content!

Why Film Needs Venture Capital

Part of creating a sustainable revolution in the film industry is creating a new system of finance. For that, we should look to other industries starting with Private Equity and Venture Capital. Here’s how we do that.

A lightbulb next to a chart outlining the allocation of venture funds in 2011 above a text blurb outlining the data source.

There’s an old joke that goes something like this. Three artists move to Los Angeles, a Fine Artist, a poet, and a Filmmaker. The first day they’re in town, they check out the Mann’s Chinese Theater. When they get there, a wave of inspiration overtakes them. The fine artist says, “This is incredible, I have to draw something! Does anyone have a piece of chalk?” Low and behold a random passerby happens to have one, and hands it over. The fine artist does a beautiful rendering on the sidewalk.

Watching this, the poet says, “I’ve had a flash of inspiration, I must write! Does anyone have a pen and paper?” It happens to be a friendly sort of Los Angeles day, and someone hands over a pen and paper. He writes a beautiful Shakespearean sonnet about his friend’s artistry with the chalk.

The filmmaker says “This is amazing, I’ve got to make a movie about it! Does anyone have any money?”

Even though the costs of making a film have been cut drastically, the joke remains true. I mentioned in my last post that the film world is in need of new money, and that what the film world really needs is something akin to Venture Capital. I think the topic deserves more exploration than a couple paragraphs in a post about transparency.

Venture capitalists bring far more than money to the table. They also bring connections and a vast knowledge of financial and industry specific business knowledge to the table. Essentially these people are experts at building companies, and when you really break it down the best films really are just companies creating a product.

The contribution of connections and knowledge is just as vital to the success of the startup as the money is. We have something somewhat similar in the film world, it’s generally the job of the executive producer to find the money for the film and put the right people in place to run the production and complete the product.

The biggest problem is that good executive producers with contact to money are few and far between, and there are very few connection points between the big money hubs and the independent film world. Filmmakers often don’t only need money, they need to have an understanding of distribution and finance that many simply do not have, and most film schools just do not teach. These positions are generally not full time positions, and most filmmakers just don’t have the money they need to pay people like this. If a venture capital model were to be adapted in film, the firm could link to these experts, and included in the budget for the film at a cost far less than it would normally be, because the person could split their time between all of the projects represented by the firm.

Most people understand that filmmakers need money, what many people do not understand is that there are very valid reasons for an investor to invest in film.A good investor knows that a diverse portfolio is far better than one that focuses solely on one industry. Industries can change and the revenue brought in by any single industry can crash with little notice. Savvy investors will seek to have money in many pots as it really helps to weather through downturns. Film is considered to be a mature industry, and has grown steadily over the past several years, even in the economic downturn. In fact, the film industry is moderately reversely dependent on the economy, so it often does better in economic downturns.

The biggest problem is that most investors just don’t invest in things they don’t know. Investors need to understand an investment before they put money into it.

Film is a highly specialized and inherently risky business. All the money goes away before any comes back, and that can scare off many investors. Especially since they often don’t understand what a good use of resources for a film is and are often incapable of seeing when the project should be stop-lossed as to not lose any more money.

One solution a venture capital firm could bring to this industry that single investors simply cannot is stage financing. Stage financing is a system of finance that is widely used in Silicon Valley. The concept is basically that the investors only release funds once certain checkpoints are met. Single angel investors do not have the time or expertise to act in this way, which is a big part of the reason for the standard escrow model. If a project that makes it through the screening process is only given the money they need for pre production up front, they must pass a review to have funds released for principle photography then it becomes a far more sustainable investment.

Filmmakers may balk at the idea of review, but quite frankly so long as the production is being well managed, they should be able to complete the checkpoints and have the additional funds released with little difficulty, assuming that the right review panel is put in place. The fund itself has every reason to see it’s projects through to completion, so it will only be filmmakers who are not doing their jobs that end up not passing the review process.

Edit: Additionally, there are deals that can be made to help agents and bankable talent feel more comfortable with such a process. This may be a subject of a later blog, and is mentioned in the comments.

Why does the fund have every reason to see films through to completion? Because if the films are not completed, then the fund will have lost all the money it put in with no chance of getting it back. That said, if the production is a disaster, and it’s clear that additional funds would not actually result in a finished and marketable film, then it is far better to cut losses and move on with other projects that have higher potential for revenue.

As mentioned in the last blog, a lack of transparent accounting is also a big issue with investors.

A single filmmaker does not really have the ability to negotiate with a distributor, at least not to a level necessary to resolve the transparency issue. In the relationship, the distributor has all of the power and there’s really very little most filmmakers, especially those just starting out, can do to change that.

But in film as in any industry, money talks. If there were a venture capital firm for film that only worked with distributors who have transparent books, and those distributors could then turn around and propose new projects to the venture capital firm, then some of the issues of transparent accounting could start to change. Many distributors, especially those working in the low budget sphere, are continually raising money for their own projects. So, having a good relationship with a venture capital firm is a big incentive to maintain good books and responsible business practices for filmmakers.

It got listed in the comments section of Black Box that filmmakers shouldn’t necessarily need to have that much business sense, since it takes their whole being to create. Filmmaking is indeed a collaborative effort, and it’s not a director’s job to think about target demographics and marketing strategies. The problem is the people in the film world that truly understand investment and recoupment are few and far between. Many of them also take advantage of filmmakers, as evidenced by the stories of studio accounting from Black Box. Part of what’s needed is the creation of teams that have what it takes to both tell quality stories with high production values, also get the films to market and figure out exit strategies, target demographics, and general budget recoupment tactics.

Many Film Schools just don’t teach this part of the business. Film schools focus everything on how you can make the film, and what it takes to do it, but few of them really give you the ability to actually go raise money. So what’s really needed is a new class of producer that understands the executive side. What’s really needed is a new class of investor that understands what it takes to invest in film, the risks, the rewards, and how it’s diversified. What’s really needed in film is a company that can successfully link the two together, and create a new class of media entrepreneur. What’s really needed is an incubator for independent film with a team that can execute both of these aspects and create a sustainable business model out of it.

Right now no such organization really exists. Legion M has some elements of it, but they miss the new talent discovery elements in favor of risk abatement. Slated works similar to AngelList, but I’m not sure their track record is what it needs to be to justify their price point. I’ve been trying to start one between my various projects with angel groups, Mutiny Pictures, Producer Foundry, and other ventures. It’s clear that the industry is changing, but quite frankly it needs to. The best way to effect the change in practices that need to happen in the industry is to change the way the industry is financed. The entrance of a film fund that operates on principles more akin to the aspiraations of a venture capital firm would do just that, and is exactly why it needs to happen.

If you enjoyed this blog, please share it to your social media. You should also join my mailing list for some curated monthly blog digests built around categories like financing, investment, distribution, marketing, and more. As well as some templates (including a deck template) as well as other discounts, templates, and other resources.