The Underlying Cause of Many Issues Facing The Indiefilm Industry.

There are many issues independent filmmakers complain about when it comes to the indie film business, many all stem from the film industry coping with he same problem, Uncertainty. This article expands on that to help creatives better adapt to it.

As an independent filmmaker, you probably didn’t get into the game to sell widgets or do insurance paperwork as your primary 9-5. As such, it’s completely understandable that indie film producers wouldn’t really consider the distributor’s perspective when making their independent films. Filmmakers got into the industry to make movies, which is an all-encompassing goal in and of itself.

Speaking from the other side of the negotiation table, there’s an issue that most independent filmmakers just don’t consider when they’re setting out to monetize their work. That issue is around the uncertainty of market demand that really only matters at least three years after you write your script, as well as the uncertainty that requires distributors and studios to plan for the inevitable unpredictability of that faces the film industry and likely always will.

This article is meant to outline some of the issues associated with uncertainty for those creatives so that they can better account for it down the line.

Content is King, but only if it’s good

For a long time, I thought that the saying content is king was primarily a platitude said by speakers at conventions to keep filmmakers making films. Obviously, distributors need films to sell in order to run their business. What most speakers leave unsaid is that there is such a gargantuan dirth of under-monetized independent film out there I thought it was something primarily meant to keep the film buyers in a superior position so they could get away with some of the shenanigans we all know independent film distributors and sales agents for. Having led a distribution company for a few years, I can say that both I and the speakers who say content is king on stage were wrong. Content is king, but only if good.

Well-made, engaging, commercial films will get distributors fighting for the right to distribute. Bad films will get bad deals which means the filmmaker is unlikely to ever see a cent. Unfortunately, the same is true for good films in a non-marketable genre, or with a hard-to-define audience.

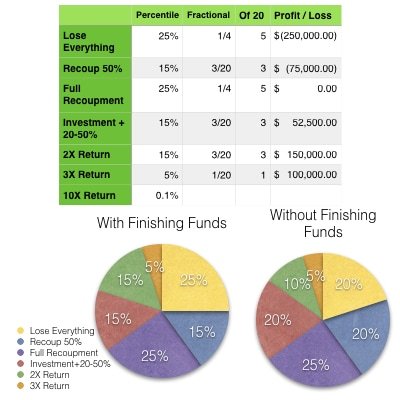

Only about 1 in 10 films makes money

After having released many movies, I can tell you from experience that only about 1 in 10 films will make enough money to cover their budget over the course of a 7-year term distribution agreement. I know that’s a rough pill to swallow, but you should know it going in. About 20-30% of the others can make a meaningful portion of their budget back over the same time period if they’re working with an ethical sales agent or distribution company. The rest will get little to nothing back. Again, all of that is assuming you have a distributor or sales agent who actually pays you and is transparent in their bookkeeping, which is rare. This basic reality of the business influences many more choices made by your distributor than you may realize and greatly informs the business model and operations of distributors.

Nobody can pick winners all the time.

In the words of William Goldman, nobody knows anything. Having said that, I think Goldman’s statement is overly broad. I think there are so many factors that weigh on a single film’s success there’s absolutely no way that even the best distributor or analyst in the world could Plan for and create hit after hit. Pixar did in their early days, but they also had a functional monopoly of hot new technology and the finances and resources of Disney, so it’s not exactly a realistic use case for those of us operating on the independent side of the industry. In the world of distribution, if you get about half of the acquisitions you make to over-perform expectations you’ve done extremely well and you would be inducted into the hall of fame if we had one. On average, the best of us only get around 35%, but even if you get around 25% you’re still doing pretty alright and will likely keep your job.

This functionally means that even if your sales agent or distributor is being entirely genuine about their expectations for the film there’s at least a 50% chance they won’t be able to live up to their most optimistic projections. Again, I don’t mean this as a slight to those of us who work in acquisitions. There are so many variables that are impossible to predict. One example of such unpredictable complications (at least for the time) would be the initial release of The Boondock Saints hitting theaters the same week as the Columbine Shooting in Colorado. While mass shootings are sadly a near-daily occurrence in the US in 2023, Columbine was one of the first of its kind. Due to a fear of inadvertently endorsing vigilante justice, most theaters that were set to play the film dropped it. For a while this made The Boondock saints was one of the biggest box office bombs in movie history.

There’s no way a studio executive, writer, producer, or anyone involved in the release of this film could have predicted that, and as a direct result the film massively underperformed. Since it was a pretty modest budget for the time and the film found a second life as a cult classic it’s likely it remained as big a flop as it started.

Granted, this is an extreme example, but it is indicative of the butterfly effect that can cause even the best film with the best team to underperform.

Producers can’t always be relied on to help market their work.

Marketing a film is expensive and time-consuming. If you don’t have a big name to help you make a big splash, you’re going to need to help your distributor spread the word about your movie if you want it to find success. There are so many films released on a weekly basis that without the filmmakers helping to push the film to rise above the white noise caused by the glut of feature film releases the film doesn’t stand much of a chance of finding an audience. Unfortunately, not all producers can be relied upon to help market their own work.

Even at this late date, many producers feel that it should be entirely on the distributor to make their film a success. After all, isn’t that what their commission and their fees are for? While I can understand the sentiment and I even agree that most distributors should do more to earn their commissions it’s not as simple as it sounds. Independent Film Distributors have a lot more to do than it may initially appear. Delivery to each platform is extremely time-intensive, and we also need to handle a lot of regular pitches, shifting mandates, filmmaker relations, investor relations, buyer relations, press relations, and a whole lot more. If you work with us to make our job easier, you’ll get more meaningful attention paid to your film as we won’t have to spend time identifying and engaging with the core audience.

In the end, if you won’t promote your own work, how can you expect anyone else to? For more, read this blog.

RELATED: Why you NEED to help your distributor market your film (If they’ll let you)

A known cast helps everything, but the competition is fierce, and not everyone is honest.

In general, the best way to rise above the white noise created by the glut of independent films released on a regular basis is to attach a star to your film. I know, I know. Everyone says this, and it’s both hard and expensive. While it’s not as hard or expensive as you may think if you do it properly, it’s still outside the reach of most sub-100k feature filmmakers. If you do get a celebrity attached to your feature film, you’ll almost certainly get a lot of distributors coming to you in an attempt to procure the rights to your film.

Unfortunately, a mediocre genre film with a B list name in it is more likely to garner a decent return than a great film of the same genre without a name in it. Of course, exceptions exist but it is a key indicator that’s likely to lead to success.

The issue here is that while you may be able to get multiple distribution offers for your film, not all of them will be companies you want to work with. Most sales agents and distributors will do whatever they need to in order to get the film from you. After they get the film, whether they even live up to their own contract isn’t a guarantee. In most cases, it’s exceptionally difficult to get your rights back.

The outcome? Consolidation and risk aversion, Exploitation of Filmmakers, or sales agents make their own micro-budget content.

There have been massive industry-spanning consequences resulting from the high level of uncertainty coupled with dwindling revenue from physical media and transactional video-on-demand sales. Many of the resulting decisions that have led to extreme consolidation of the industry are made simply out of a need for the sales agent or distributor to make payroll, although often those issues extrapolate into something else. Additionally, almost all of them are bad for filmmakers.

The most obvious example of negative consequences for filmmakers is the fact that many contracts are structured in a way that exploits filmmakers by passing through disproportionate risk and falsified expenses. This is covered across the internet so I won’t go too far into it here. Additionally, in the last few years, the industry has been consolidating into the hands of fewer and fewer companies. This leads to less competition for acquisitions, which means lower payments, less transparency, and an explosion of growth in the exploitation mentioned above. Simply put, when there are fewer companies who can buy your film, they don’t have to do as much to get it.

Given all of this uncertainty, sales agents and distributors are less likely to acquire content outside of the standard genre fare they know they can sell. This means newer voices and content are likely to get lost in the shuffle. In order to combat this, some sales agents have started their own production lines to develop content that fits the needs of their buyers. The most notable recent example of this was Winnie The Pooh, Blood & Honey Which was made by ITN Studios. ITN was a distributor and sales agent for quite a while before Stuart decided the best move was to create a bespoke model for his buyers. It worked wonders and many sales agents are following their example.

The problem with the direct production model is primarily that it creates a new kind of competition for filmmakers, and could quite easily mean that the traditional method of acquisition for independent films is disrupted in a way that leaves independent artists completely out in the cold.

Again, all of these issues are greatly influenced if not caused by the issue of uncertainty of the independent film industry. Uncertainty faces every industry, but the level of it is significantly greater than in most other industries outside of early-stage high-growth startups or perhaps certain types of small businesses. However, there is one thing that is certain for filmmakers. If you sign up for my Newsletter you’ll get my independent film resource package which includes an independent film investment deck template, festival promotional brochure template, monthly content digests segmented by topic, a free e-book, white paper, and more! Click the button below to add it.

Thanks for reading, more next week, and please share this if you liked it!

Check out the tags below for related content!

6 Things stopping a sustainable investor class in film.

If you’ve ever raised money to make a film, you know it’s hard. It’s not because individual films can’t be good investments, it’s that the problems with the industry are systemic. Here’s a look at why.

Much of this series has been focused on the numbers behind film investment. While metrics like ROI and APR are very important when considering an investment, they’re not the only reason that high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) tend to shy away the film industry. Here are 6 things that are stopping them.

In order for independent film to develop a sustainable investor class, the asset class itself needs to be taken more seriously. The reason that no one has yet been able to create a sustainable asset class out of film and media is much more complicated than the numbers not being in our favor. In this post, we’re going to examine some of the other things stopping independent film from becoming a sustainable asset class. This list is in no particular order, except how it flows best.

1. LACK OF INVESTOR EDUCATION

Investors tend not to invest in things they don’t know or understand, at least as anything more than an ego play. The Economics behind film investment is difficult to understand even before you factor in how difficult it is to find reliable information on film finance from an investor’s perspective.

Even the basics of the industry can be difficult to learn. Generally, film investors are forced to read older, often out-of-date books on film financing targeted more at filmmakers than at investors. This industry is in the midst of a reformation, so much of the information is out of date before it’s published. Most investors don’t really spend a long time learning information from a different perspective which may or may not be correct.

Whit that in mind, many Investors learn how money flows in the Film industry from the filmmakers they invest in. Apart from the conflicts of interest, there’s another rather large problem with that strategy.

2. FILM SCHOOLS DON’T TEACH BUSINESS AS WELL AS THEY NEED TO

Film Schools can be great at teaching you how to make a film, but they’re generally not good at teaching necessary business skills. Even things as basic as general marketing principles, how best to finance a film, or how to make money with a film under current market conditions.

While film and media are an artistic industry, focusing solely on the quality of the film is not going to recoup the investor’s money. Film Schools aren’t great at teaching branding filmmakers how to define their core demographic, or how to access them once they have.

3. DISTRIBUTION ISN'T WHAT IT USED TO BE.

The big risk in film distribution used to be the gatekeepers. You had to make a good enough film to attract a distributor so you could get your film out there. However, that problem has been traded for an entirely different one, oversaturation of content. I would argue that a new problem is harder to overcome.

The old model was that the home video sales would be able to make a genre film profitable, even if it wasn’t that good. Essentially, if you had access to a wide-scale VHS or DVD replicator, you could make a mint selling the licenses. There wasn’t much competition, so a cottage industry sprung up around film markets.

That model worked when it was much more expensive to make a film. Given the high barrier to entry from needing to raise enough money to shoot on film, as well as develop the skills to expose it correctly, there was relatively little competition compared to the demand. However, now that anyone can make a film with an iPhone and 500 bucks the marketplace has been flooded.

Additionally, since the DVD Market has all but dried up, it’s difficult to make a return for newer filmmakers. VOD (Video On Demand) Numbers haven’t risen to the occasion, since most people can get their fix from watching Netflix. It used to be easy to sell DVDs as an impulse buy at the checkout line. Now that everyone has hundreds of free movies at their fingertips, Why should they pay 3 bucks to watch something when there’s an adequate alternative I can get for free?

So the problem is now less how to get distribution, and more how to market the film once you’ve got it. It’s both hard and expensive to market a film. Generally, it’s best to create something of a hybrid between these two types of Distribution. However, there are issues with that as well, and these are less associated with expertise.

4. SEVERE LACK OF TRANSPARENCY IN INDEPENDENT FILM

I’ve written before about the lack of transparency in Distribution, so I won’t go into too much detail here. In Essence, the black box that is the world of film distribution is very intimidating to many investors. Investors want to be able to know when their money is coming back, and many filmmakers are unable to make any real promises about that. However, there’s another issue with transparency from an investor’s perspective.

Unfortunately, many filmmakers don’t communicate well with their investors or other stakeholders. I’ve spoken with many film commissioners, investors, and others about their frustrations with filmmakers not keeping them in the loop.

Filmmakers understandably focus on the admittedly difficult task of making the film happen. Between all of the tasks like scheduling and budgeting the film, finding the locations, confirming the crew, making the shotlist and storyboards, sending out call sheets, and a whole lot more, it’s easy to let communication fall by the wayside.

5. INVESTORS LAST TO BE PAID

Now I know that Filmmakers are reading this thinking “BUT I GET PAID AFTER THEY GET 120% BACK!?!?” To a level, you’re right. However, unless you waived your producer’s fees, you got paid before they did. Sure, you did a lot of work for often too little money to make your film happen, but you did get a fee to produce this film. If your investor wanted to be cynical about it, you produced or directed a movie for hire that you got to take most of the credit for.

Here’s what a waterfall for a film normally looks like. Investors generally did a lot of work to get their money, and now they’ve paid you to make a film and it’s unlikely they’ll ever get all of their money back.

1.Buyer Fees

2.Sales Agent Commission

3.Sales Agent Expenses

4.SAG/Union Residuals

5.Producers Rep (If Applicable.)

6.Production Company

7.Gap Debt (+Interest)

8.Backed Debt (+Interest)

9.Equity Investor

I may be persuaded to do a financial analysis of what that would actually look like in terms of money. Oh look, I did a blog explaining exactly what this means. Click here to read it.

6.LACK OF ACCESS TO TASTEMAKERS AND CURATION

We explored the numbers of why indexed film slates just don’t work in part two. However it takes a fair amount of training, experience, and a bit of luck to recognize what films will hit and what films won’t. While William Goldman is famous for saying “nobody knows anything,” there has to be a balance between a dart board with script titles and industry experts guiding the ship.

Developing an eye for what makes a successful film is something that most prospective film investors don’t want to take the time to learn, especially since many get burned on their first investment. it takes a lot of time to understand what projects have what fit in the market, and that’s generally not something that an investor has time for.

Having a few sets of experienced eyes looking over what investments would be good to fund is something that could make independent film a more sustainable asset class, and not enough investors have access to it to avoid getting burned.

So, what is there to be done about it? Check the next post for the final installment, How do you make a sustainable asset class out of film?

Also, if you like this content you can get a lot more of it through my mailing list. You’ll also get a FREE film business resource package that includes an investment deck template, contact tracking templates, money-saving resources, a free e-book, and a whole lot more. Again, totally free. Get it below.

Click the tags below for more articles on similar topics.

Can a Film Slate Make More than a Tech Portfolio?

Most people know film is a bad investment. There is one potential saving grace though.

Edit from the future: Maybe, but probably not, and don’t count on it.

In a quote often attributed to Albert Einstein, “The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.” He also called it “The 8th wonder of the world, he who understands it, earns it. He who doesn’t pays it.” In this post, we’re going to be examining how we can use the notion of compound interest in comparison to tech and film investments.

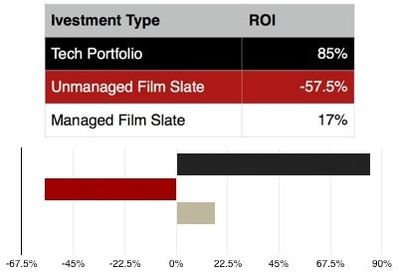

In the previous installment, we looked at the average ROI of a film slate vs. an early stage tech portfolio. Here’s what we came up with before. For the full tables and Metrology, check out last week’s post.

Unfortunately, the numbers don’t look good for film. By the math above, we can see that tech portfolios make on average of 7.5X what a film slate would over their lifespans.

But, film does have one advantage over tech. The amount of time that it takes for a film to recoup [if it’s going to] is much shorter than what it would take for a tech exit would be.

For instance, the average time from when an Angel becomes involved in a project to when they see their money back is around 12 years. For a film to at least start recouping investment, that time period is around 2-3 years, if it’s done well and distribution is planned from the beginning.

Why is that? Generally, for a tech investor to get their money back, the company they invested in has to either be acquired by a larger company or make an initial public offering [IPO] and be listed on a stock exchange. Sometimes an investor will be able to list their stock on a secondary exchange, but that’s a little beyond the scope of this article. Acquisitions tend to happen more quickly than IPOs, but there’s generally less money and less prestige.

Given that the size of venture capital [as opposed to angel investment] rounds have ballooned in the last decade, many venture capital firms are pushing their companies to IPO instead of be acquired. This may make the time from an early round angel investment to exit take even longer than the 12 years mentioned above.

Films, on the other hand, start getting some of their money back shortly after they start distributing the film. If the filmmakers get a minimum guarantee [MG] they may get a decent check up front. If they don’t, they may not, and it may take an additional year or so to start getting their money back. I should note MGs are more the exception than the rule.

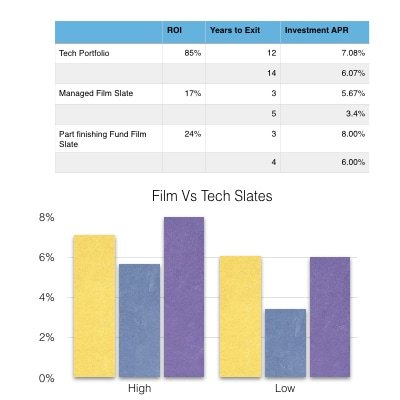

So for this exercise, we’re going to look at the APR of both a technology investment portfolio and a film slate. We’re going to make the assumption that both investments are early stage, since the angel round for a technology company is very early in the investment process, generally directly after the friends and family round. Later rounds are generally dominated by institutional investment firms. A similar scenario can be said about film. Most angels from other industries get involved very early, since they don’t have contacts with completed projects.

Since revenue from a film tends to come in over time, we’ll count the lifespan of a film investment to be 3-5 years as opposed to the 2-3 years mentioned above. 3-5 years should be enough time for 60-80% of a films total revenue to come in on average. As such, since this series is largely a thought experiment we’re going to think the general earnings of a film to come in overt that shortened timeframe. Tech exits on the other hand generally come with a large lump sum for the investor after a quite a long time that may be getting longer, we’re going to do the math based on 12-14 years to exit for a tech company. Some do come in much faster, but some films also get bought out for millions after 18 months. They’re outliers and not generally worth accounting for when planning to pitch an investor.

Tech portfolio APR

When we compare APRs, this is starting to look a little more reasonable, but still not great. When we compare the APR of a film as opposed to a technology company, we’re only looking at around a 1.5X to 3X instead of a 7.5X differential. Unfortunately, looking at things through this lens raises other issues, in that the average mutual fund pays out around 5-7% APR, depending on the health of the entire economy.

Could a savvy investor do any better? Perhaps.

Everything we’ve been looking at so far has assumed that all of these investments were early stage. If it were a tech investment, we’d say Seed or Series A, in film, we’ve been assuming these investments take us out of development and into preproduction. But what if we were to include completion funding and distribution funding in the portfolio? I would do a similar analysis for technology companies, however, given that the VCs and hedge funds dominate that world due to the amount of capital needed. In days and years past, these stages would be overwhelmingly covered by distributors, but that’s nowhere near as true as it used to be. This leaves a hole for an investor to come in and increase their potential returns while lowering their risk exposure.

The assumptions I’ve made on the chart above are that the slate would be made up of half of finishing/distribution funds, and half of the early-stage investments. As such, the risks are far lower, and since much of the later stage debt may be done in the form of debt as opposed to equity, we can assume not a huge amount of loss on those investments. Also, since the film needs to be finished and not made from the start, the time for the recoupment of these funds is greatly lessened. With that in mind, we'll assume that the bulk of these returns come in from 3-4 years instead of 3-5.

I'd like to take this opportunity to remind you that none of this is meant to be scientifically accurate, but rather a very good estimate and approximation of what these slates could look like given the right set of circumstances. Take these numbers with a grain of salt, just as you should any revenue projections from a pre-seed stage startup or revenue projections from a filmmaker. This also should not be considered financial advice, nor a solicitation for sort of funding.

Admittedly, these numbers are highly speculative, [See disclaimer on part 1] but the right team backing up the right filmmakers may make it possible. Given I work with investors, I should state these do not constitute any legal documentation, it’s really just a theoretical exercise to help compare two asset classes. Again, not a solicitation.

By creating a slate investment that includes completion funding as part of the investment mix, we lessen the risk and decrease the time to getting the money back. How does that affect the APR?

With the inclusion of completion funding in a portfolio, the APR of a film slate is looking relatively competitive. If you’re an investor, you may be asking yourself, “Well if it makes that big a difference why not focus only on completion funding?” It’s a great question, there are many funds that do. So many in fact, that the playing field is getting fairly crowded. Especially when you compare it to the other funds that focus on development throughout the film industry.

If a fund only offers completion funding, It would be difficult to establish the long-term relationships with the emerging talent necessary to make an organization like this work. It would also be harder to attract high-end prospects for bigger films with more recognizable names. If a fund does a mixture of the two, it can be a very good way to find new filmmakers and help them pass the goalpost on their first film. Once they’ve done that, you can start to work with them on future projects at an earlier stage. By doing this, the fund creates a better vetting process and attracts higher-end talent.

With that in mind, a mix of investments seems to further the goals of the organization and the industry in a much more cohesive manner. It also starts to sound a lot like Staged Investments, like Seed Stage, Series A, B, C, and the like. Don’t worry, we’ll have a much more in-depth conversation about this later in the series, as well as a couple of other blogs on the site tagged “Staged Financing”

But first, We’re going to talk about some of the excitement associated with both of these types of investment. The Decacorns and Breakouts. That blog can be found below. Again, for legal reasons I need to state that none of this should be considered financial or legal advice, as I am not a lawyer nor a financial advisor. Further, this is not a solicitation for funding or investment.

The only thing I will solicit you to do before finishing up this beast is a blog is to join my mailing list so you can grab my free film business resource package. (segues, eh?) It includes a FREE Deck template to help you talk to the investors you’re probably considering approaching if you’re reading this. It’s also got a free e-book, and other money and time-saving resources. Check it out below.

Black Box - a Call for Transparency in Film

The concept that Film Distributors aren’t telling you the whole truth isn’t unknown. However, the problem is deeper than you may realize. Here’s why.

A Black cube on grass in a yard, with the Title “Black Box” in the upper left corner and the subtitle “An In Depth Analysis of ‘Hollywood accounting” in the lower right corner, and logos for Guerrilla Rep media and PRoducer Foundry in the lower left corner.

Photo Credit thierry ehrmann Via Flickr, Modifications made to add title, subtitle, and logos

The process of Filmmaking has been evolving rapidly over the past decade. With the massive change in the availability of equipment, negating the need for tapes or stock, and bringing the professional quality down to a price point thought unfathomable merely a decade ago, the barrier to entry for making a film has been almost completely obliterated. Additionally, education on how to make a film has become widely available, from the massive emergence of film schools to a plethora of information available in special edition DVDs, anyone can learn how to make a film. However, the same cannot be said for Film Distribution. Film distribution is still a black box from where no light or information emerges. There is a very palpable air of secrecy around film distribution, and now that film production has become available for anyone curious enough to seek it, it’s time the same is done for film distribution.

I’ve always loved movies, and I’ve been making films in some fashion for nearly a decade. Even though that’s really not that long, I realized that when I started, camcorders were still fairly rare among middle-class families, and far rarer among high school students. Even the local Access channel worked with three-chip cameras, and those who could afford it swore by the film. That landscape is now nearly unrecognizable, now every other high school freshman carries a 1080p camera in their back pocket anywhere they go. This process has been going on for decades, far longer than my personal experience.

In the 70s, even Super 8 home movies were few and far between. To make a movie in the 70s involved an incredible amount of time, effort, and skill. Many learned by trial and error, with limited training and education often in the form of watching the great films of their eras. In those days, no one went to Film School, because there really weren’t that many of them. You pretty much had to go to New York or LA.

Even those who entered the industry in the 60s and ’70s often went to school for something else. Today, there are 389 Film Schools spread across 43 states, which considerably changes the landscape for Education.

However the same cannot be said for film distribution. Despite the fact that technology has evolved beyond what even the most visionary filmmakers could scarcely imagine back in the 70s. Much of it is still a black box where even the most simple information about budgets and returns are kept largely under lock and key. Studio accounting and net proceeds are just as secret now as they have been since Jimmy Stewart became the first Actor to be a net profit participant back in the 50s.

Even if you made a film that’s being represented by a distributor, many of them will not share accurate information regarding the returns you’ve made. A simple balance sheet is difficult to track down, and even if you can get one it’s often hindered by studio accounting, and the breakeven point is never reached, so the filmmaker never sees his or her share in the net proceeds, also known as profit participation. If filmmakers don’t make money making films, then all they have is an expensive hobby that is unsustainable in the long term. The problem is so vast that even Star Wars Episode 6 never made a profit. Even if they can get their first project bankrolled, unless they can make a profit on their film it is unlikely that they will get to make another one. In the independent film world, most times if the producer never sees their share in the net proceeds, then neither does the investor who footed the bill.

If the investor doesn’t see profit, then they won’t be an investor for long. Unlike the filmmaker, most of them won’t continue to do this just for the vision. The first thing any savvy investor will tell you is that they only invest in what they know. And while they may now be easily able to find information on the process of making the film, the metrics measuring the performance of independent films are unclear and almost always unreliable. If an investor can’t decode and project revenue through clearly definable analytics, most of them are far less likely to close an investment deal. Even if they do invest, if they feel like the distributor is not telling them the whole story, they generally won’t invest again.

If the Industry is to change, new money to enter it. The old money is tied up in sequel after sequel, and rehashes of old stories. The movie-going public is fed up with it and want something new, different from the old franchises. This leaves a demand in the industry for quality content that is simply not being filled to the extent it needs to be. In a way it’s similar to the ’60s and early ’70s here in San Francisco when Venture Capital was just starting, there are many talented young people with great ideas, but little business sense.

The studios are entrenched in the old ways of thinking, and behemoth companies don’t adapt well to change. Startups do adapt well to change, and they really can change thought processes through ideas that take hold. The Film Industry is changing more rapidly than ever before, it will likely be just as unrecognizable in another 5 years as it was 10 years ago. Anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The old companies and the old money can’t adapt as quickly as things are changing, so logically we need new ideas and new money to enter the industry and shake things up.

This is exactly the effect that Venture Capital had when the Traitorous Eight left Shockley Semiconductor to start Fairchild, and then left to start other companies that eventually became Silicon Valley. Fairchild was only able to be started due to a new idea that evolved into what is now known as Venture Capital. In order to effect change as quickly as is needed, something similar must happen in the film industry. But Venture Capital can’t enter an industry where the risks are incalculable. Without a more transparent method of accounting, the risks are indeed incalculable.

The industry is evolving more rapidly than ever before. The future is unclear. It’s a wide-open frontier where anyone can make a movie, even with a small device they carry in their pocket. The process of film production has moved out from the dark rooms and light-proof magazines of old and exposed for all to see. It is time for the business side to do the same. It is time for every filmmaker and investor to have a clear understanding of Distribution. It is time for daylight to expose the studios’ accounting practices. It is time for transparent accounting in film.

While there's not a lot an individual can do about the lack of transparency in the film industry as a whole, there are ways that we as individuals can band together to have an impact. Those tactics are some of what I tried to implement at Mutiny Pictures, and what I address in my content, groups, and consulting. One of the goals of porting over my website was to greatly lessen advertising and sales, but check the links below to learn more about ways you can impact not only your career but the industry as a whole. More details on each of the buttons found below.